Once the capital of the Kingdom of East Anglia in the Anglo-Saxon Period, today Dunwich is just a small village consisting of just a few streets, a pub, and a few houses.

Nature hasn’t been kind to Dunwich over the centuries and now almost all of the town and the whole harbor have been absorbed by the sea, mainly because the town is hit by huge storms on an annual basis, causing massive coastal erosion. In medieval times, this was an international port that rivaled London in size.

The first losses of land are recorded in The Domesday Book when over half the taxable farmland was lost to the sea between 1066 and 1086. After the book completion in 1086, Dunwich had an estimated population of 3,000.

The city devastation began in 1286 when huge cyclones hit the East Anglian coast. It was followed by two great storms the next year. The most extensive damage to the city was caused by another great storm in 1347, which resulted in the destruction of almost 400 houses. And the Saint Marcellus’ flood on 16 January 1362 destroyed what was left of the town, reducing it to the size of a village. Almost all of the buildings and seven churches disappeared under the sea.

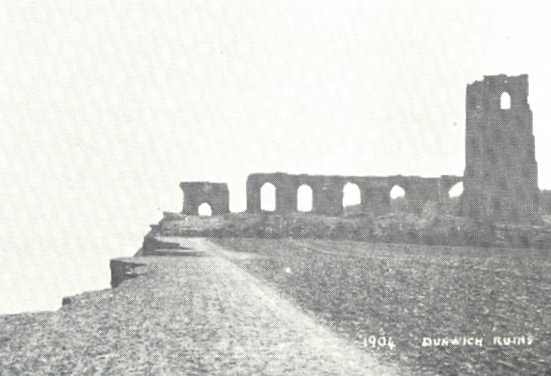

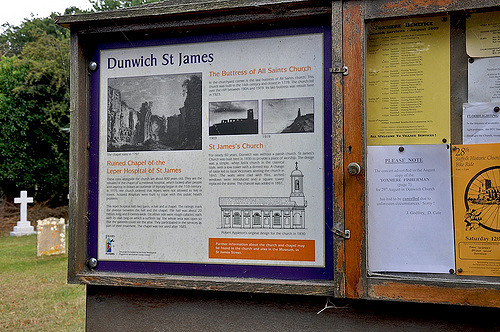

By the mid 19th century, Dunwich’s population had dropped to only 237 inhabitants and it was described as a decaying borough. The last remaining church, All Saints, disappeared during the early 20th century, with the last portion of the tower succumbing on 12 November 1919. It had been abandoned since 1755, and today only a final fragment and a single tombstone of All Saints Churchyard remain.

In 2008, the Dunwich project was created, funded by the English Heritage Trust and the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation.

Their intention was to make an underwater survey, combined with aerial photography by using all reliable historic mapped data. New digital maps were produced by a marine archaeologist, Stuart Bacon, the Geodata Institute, and Prof. David Sear of Southampton University.

By also using multi-beams and side-scan sonars, these surveys identified a series of ruins which were confirmed by divers who recovered stones with lime mortar from the sea.

They matched nearly perfectly with medieval mortar in existing churches on the coast. And further in 2010, BBC Oceans used novel acoustic imaging cameras to film the ruins through the turbid waters.

The large survey and update of the mapped data were reported in 2012. The results were enormous. The whole research produced the most comprehensive survey of the Dunwich townsite, which is considered the largest medieval underwater site in Europe.

Dunwich is now a tiny village of barely more than 120 people and a few offshore fishing boats, a friendly 17th-century pub, a well-known beach café and of course, a museum devoted to its fascinating history. However, the sense of absence still affects the village, with the realization that within another century it may well disappear for good.