On the morning of October 25, 1960, skipper James Dew set out on the River Severn from Worcester, England, at the helm of his barge Wastdale H.

He embarked on the return journey with a cargo of 380 tons of petroleum spirit, leaving Avonmouth Docks at around 7:15 p.m. Among the many other barges on the river that evening was Arkendale H, skippered by George Thompson. The Arkendale had set out from Swansea, South Wales, on the afternoon tide and was carrying 300 tons of Britoleum fuel oil.

When the two met at approximately 10:00 p.m., it was to have disastrous consequences. The two vessels collided, first with each other, and then with one of the upright columns supporting the bridge.

The barges were jammed against the pier column as the two spans on either side came crashing down. The impact caused their cargoes to ignite–it seemed as though the very river was on fire as the burning liquid spilled out.

Luckily the bridge was closed that night from 9:15 p.m. for strengthening works, so there was no chance of a locomotive plunging into the water. Even more luckily, the workers had retired to the signal box to listen to a boxing match on the radio–they were fans of the English heavyweight Henry Cooper.

But the Severn Rail Bridge did carry a gas pipeline, supplying gas from Sharpness on the English side to Lydney on the Welsh side of the river. As the bridge broke apart, the pipe ruptured.

The ensuing fire, according to the BBC archives, spanned the entire river and was visible through the fog from Coaley Peak viewpoint, which is about ten miles inland from Sharpness Dock on the English bank of the river.

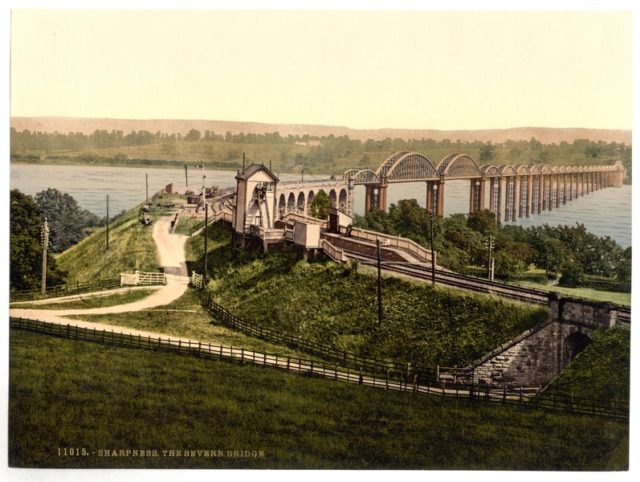

Liverpool-based contractors Hamilton’s Windsor Iron Works began construction of the Severn Railway Bride in July 1875. It was a huge challenge — the River Severn has a vast tidal range and is flanked by dangerous mudflats.

At the proposed site of the bridge, the water level rises by 30 feet in just two hours. The pier columns, 10 feet in diameter, had to be sunk through up to 28 feet of muddy silt in order to secure them in the bedrock below.

The project engineers overcame every challenge the river could muster, with the loss of just one life: workman Thomas Roberts who fell 70 feet into the water from the bridge deck. On October 17, 1879, crowds gathered to watch the first passenger train make it’s ceremonious journey along the Severn Bridge Railway.

One of the main incentives for bridging the River Severn close to Gloucester, linking South Wales with Bristol and the rail network to London, was the vast reserves of Welsh coal. In the age of steam, transporting coal was a huge and lucrative business that every railway company wanted to attract to their lines.

From it’s conception, the bridge was in competition with a planned tunnel. Both were under construction at the same time, but the Severn Bridge Railway won the race. In fact, the day before the bridge was opened, the Severn Tunnel had been flooded by a spring, which delayed further construction for a whole year.

It turned out to be something of a Pyrrhic victory. The Severn Bridge Railway failed to attract the expected level of traffic, partly because the Severn & Wye Railway had cut a deal with the Forest of Dean coal mines in 1878.

When the Severn Tunnel, which is still in use today, opened in 1886, it quickly became the favored route for most goods trains hauling coal out of the Welsh hillsides. By 1894 the failing Severn Bridge Railway Company was taken over by a joint committee of the Great Western Railway and Midland Railway.

Following nationalization of the British Railways in 1948, the entire network came under review. It was decided that a program of reinforcing the structure to allow it to carry heavier trains would give the Severn rail bridge a new lease of life.

And this brings us back to that murky October evening in 1960, and the barges Wastdale and Arkendale.

The section immediately downriver of the Severn Rail Bridge is notoriously prone to thick fog, something which Thompson had dealt with countless times. He was very familiar with the river and her turbulent tidal currents–Dew, however, had only sailed the Severn for three days. Thompson was navigating past the busy entrance to Sharpness docks when Dew, struggling to maintain control of the Wastdale on the fickle river, appeared from the gloom slammed into his port side.

“As they came together and unknown to either skipper, a crewman on the bow secured a line between the vessels.

They were now inseparable,” writes the British railways history website Forgotten Relics. Both of the vessels were out of control in the strong current and were headed towards the Severn Railway Bridge. With nothing else left to do, the crews of the two boats braced for impact.

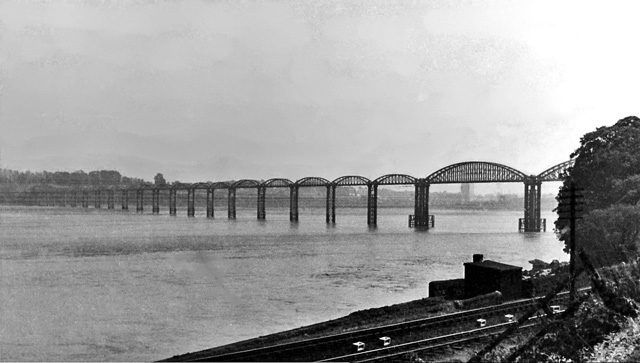

They hit Pier 17 with disastrous results. Wastdale was flipped upside-down and Arkendale ended up wedged on top of her. Five crewmen were lost — and the bridge was a mess.

Weighing up the costs of repair versus demolition was a debate that rumbled on for years. For the local communities, it was an important link, even serving as a school commute for many children. At the start of 1962, works to make Pier 16 safe were about to begin when Pier 20 was struck by tanker. Shortly after, it was hit again — ironically by the floating crane that had been brought in to repair it. This was the final straw.

Demolition of the Severn Railway Bridge took almost as long as it did to build it. Two years after the decision to take it down, in August 1967, the first contractor arrived on site. They deconstructed most of the spans, but it took a second contractor armed with explosives to remove the piers and a further two years to clean up all the debris.

All that remains of the bridge today is a stone tower that was part of the eastern approach viaduct. The wrecks of the barges Wastdale and Arkendale can still be witnessed at low tide.