It is a normal December evening, nothing out of the ordinary except for the fact that a terrible storm is raging outside. It seems as if the snowfall would never stop. People are growing concerned, for such a storm rarely hits Scotland’s Firth of Tay.

Written accounts of the day speak of winds that reached a speed of 71 mph. But everything is warm and cosy inside the train as it crosses the Tay Bridge, the brainchild of Sir Thomas Bouch.

No-one, not even in their wildest dreams, ever have thought that the masterpiece of renowned railway engineer Thomas Bouch would fall victim to the storm. But the sad truth is that it did.

It was December 28, 1879. The Tay Bridge is hit by a heavy snowfall and its construction, mostly wrought and cast iron, is slowly giving way under the weight of the snow combined with the relentless wind.

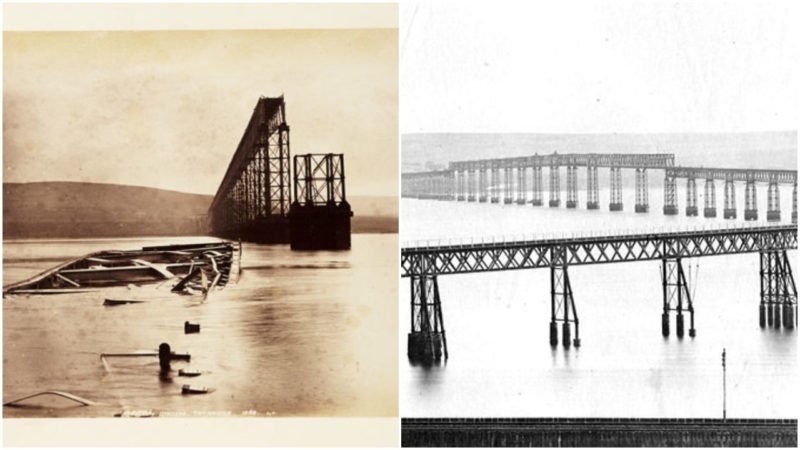

As the heavy train crossed the bridge at 7:13 pm, it was not even halfway over before the iron piers started to snap and break. In the blink of an eye, the train plunged into the freezing waters of the River Tay below. By 7:16 pm, the train was fully submerged beneath the waters.

It was a passenger train carrying 75 people: No-one survived. “The central navigation spans of the Tay bridge collapsed into the Firth of Tay at Dundee, taking with them a train, 6 carriages and 75 souls to their fate,” writes Tom Martin on his Tay Bridge Disaster research webpage.

In 1854, a proposal was made for a bridge that would connect Dundee with Wormit. But it took sixteen years before this proposal was formally approved as the North British Railway (Tay Bridge) Act. It took another year before construction officially began.

Thomas Bouch was chosen as the right man for the job. Little did he know that this would be his last project before his reputation is shredded into tiny pieces.

Tom Martin describes the disaster as “one of the most famous bridge failures and to date it is still one of the worst structural engineering failures in the British Isles.” The irony is that this bridge is what gave Bouch the title of Sir, for he was knighted once the Tay Bridge was completed in February 1878.

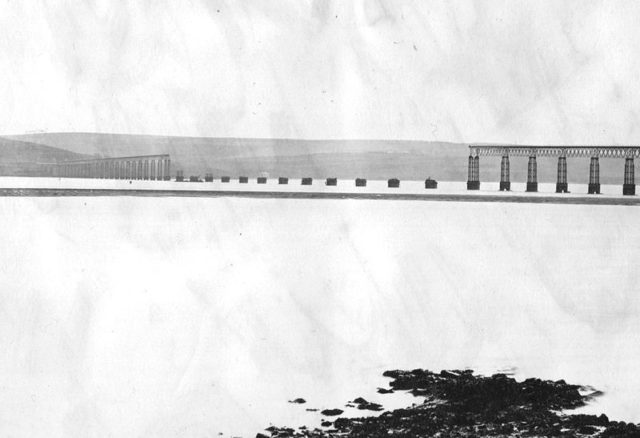

But Bouch wasn’t only responsible for the design of the bridge; the construction itself, as well as the maintenance, was his responsibility too. What Bouch constructed was a nearly two miles long bridge — enough to earn the title of the world’s longest bridge.

Carried away by the success of the Tay Bridge – shortly before the disaster – Bouch was hired to work on another project whose outcome would be yet another masterpiece: the Forth Bridge.

And then the accident happened he was immediately taken off the Forth Bridge project, for fears of another flawed design ran wild. Bouch’s original idea for this bridge was to use brick piers. But the design was later “replaced with braced cast iron columns and the number of spans was reduced which made each significantly wider,” writes Network Rail.

The investigation that followed after the collapse revealed that the bridge was poorly maintained and even worse, badly constructed. With no one else to point a finger at, Bouch was held responsible.

Bouch’s health had been deteriorating for some months prior to the disaster. His death came almost a year after the Tay Bridge accident, on October 30, 1880.

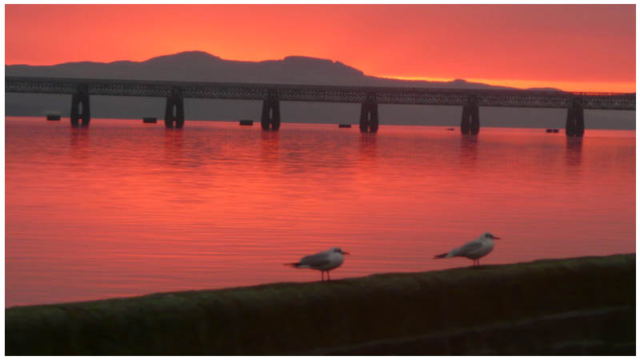

Now the waters of the Firth of Tay were without a bridge and a new one was desperately needed. The new bridge runs parallel with the course of the old one and it stands strong as ever to this very day.

But the past and the memories from it die slowly, and the stumps of the old bridge are still visible in the water as a monument to that fateful day.