The impressive ruins of Peveril Castle (also known as Peak Castle or Castleton Castle) stand high above the charming village of Castleton in Derbyshire’s Peak District.

It is one of England’s earliest Norman fortifications and is even mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 (a manuscript record of the “Great Survey” of much of England and parts of Wales created by order of William the Conqueror).

Scroll down for drone footage

The castle, or what is left of it, is now in the care of English Heritage.

For years, the castle was practically forgotten — overgrown with lush vegetation and slowly vanishing. The first cleaning activities and minor conservation interventions were done in the 19th century. Luckily, today, with the help of visitor fees, this monument of significant historic value is properly maintained and, hopefully, saved for future generations.

The material pieces of evidence discovered so far at the site, along with written documents of the era, clearly show that the castle was probably constructed between 1066 and 1086.

Unlike the earliest Norman fortifications, which were firstly built in timber, Peveril Castle was constructed in stone from the start. It was named after its founder, William Peveril, a Norman knight closely connected with William the Conqueror. He was given the title of bailiff of the Royal Manors of the Peak after the Norman Conquest of 1066.

Some historians and researchers believe that Peveril was actually an illegitimate son of William the Conqueror. Even though this assumption is still a legend not backed up with any clear evidence, it is usually quoted in the guide books.

William’s son, also called William, inherited the castle and the other properties of his father. But, in 1155, King Henry II confiscated all of his properties. Henry II visited the castle on several occasions, and in 1157 he had a meeting with King Malcolm of Scotland at the site. The mighty square keep was erected by Henry II in 1176.

The castle passed into the hands of the Duke of Lancaster in 1372, but he did not use it often. Without proper maintenance, it started to fall into decay.

By the 17th century, only the keep was used as a local courthouse, but this practice was abandoned, and little by little it became almost completely ruined until the surviving remains were systematically restored throughout the 20th century.

The keep dominates the hilltop. On its two sides, portions of the original gritstone facing can still be seen.

Currently, the remains of the keep, including the garderobe (an example of a medieval lavatory) and a small chamber with rounded windows, cannot be explored because it is closed for public visits due to extensive conservation work. However, the uphill climb to the ruins is still worth doing.

Although large parts of the castle are ruined, there is still enough to be seen. The structures that have survived the passage of the time are remarkable and silently tell the story of the castle and the region. The walk around the curtain walls and ruins is priceless.

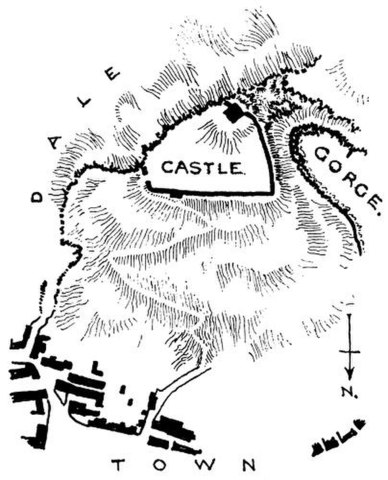

The site is nestled on a top of a hill which offers breathtaking panoramic views over the village below and the surrounding countryside, including the Hope Valley and Cave Dale.

It is approached by a steep climb from the village and through the remains of the 12th century gatehouse, located on the east side.

In the 13th century, two smaller round towers were added at the curtain wall; now, only their remains can be seen. On one of them, there are enough surviving elements to clearly show that Roman tiles were incorporated into the construction – probably removed from the nearby Roman fort of Navio at Brough.

Inside the courtyard, traces of the foundations of a hall, kitchens, and several other domestic buildings can be seen.

The Visitor Centre is open as usual. There are a few interactive displays that tell the story of Peveril as the administrative center of the Royal Forest of High Peak, a royal hunting area since the 11th century frequently enjoyed by the Norman kings and their knights.

In fact, the castle was primarily built in order to control the Royal Forest of High Peak.