Cárcel de Caseros was a once-infamous prison located in the south of Buenos Aires. It’s construction, which took two decades, began in 1960 while Argentina was under the governance of the radical politician Arturo Frondizi, and was finished in 1979 during the reign of the dictator Jorge Rafael Videla. It was initially designed as a remand center to house inmates who were awaiting their trails. But when it was opened in 1979, that purpose was changed and Caseros Prison became a place for locking up political prisoners.

At the opening ceremony on April 23, 1979, the Minister of Justice, Alberto Rodriguez Varela, gave a speech in which the prison was compared with a five-star hotel and stating that human rights would be carefully observed within its walls.

The truth was quite different, however. The building was purposefully designed so that no sunlight could reach inside the prison cells; a design that was found to be inhumane by human rights groups. According to The Argentina Independent, “Former prisoners talk of their skin turning green due to lack of sunlight, and their teeth rotting. They were kept in their cells for at least 23 hours a day, although it was quite normal to be confined there for days and weeks at a time.”

The prison itself stood next-door to even older prison of the same name, a facility that was meant to serve as an orphanage when it first opened during the 1880s but instead was converted for use as a jail.

The newer prison stood 22 stories high and was shaped like the letter H; it had no less than 1,500 cells that were capable of holding up to 2,000 inmates. Each cell was approximately 4 feet wide and 7.5 feet long; inside was a bed and toilet, as well as a small table and chair that were both bolted to the floor.

At one point, this prison held around 1,500 inmates, most of whom were left-wing supporters and militants such as the Montoneros as well as members of Argentina’s Workers’ Revolutionary Party and its militant branch, the People’s Revolutionary Army. A number of leaders of student organizations also found themselves among the prisoners there.

When the dictatorship came to an end in 1983, the political prisoners were set free and the prison took on another form — it became a prison just like any other for housing common criminals and lawbreakers.

But this is also when the population of inmates jumped considerably, well over the intended maximum capacity of 2,000 people. Once more, human rights activists warned prison officials about the overcrowded conditions within the prison cells. The solution that the government of the day provided was to remove all of the cell’s bars and thus allow the inmates to wander freely up and down the prison block. This measure backfired when a riot broke out in 1984.

During this riot, the prisoners made holes in the walls to allow sunlight to come in. These holes also made communicating with the outer world possible.

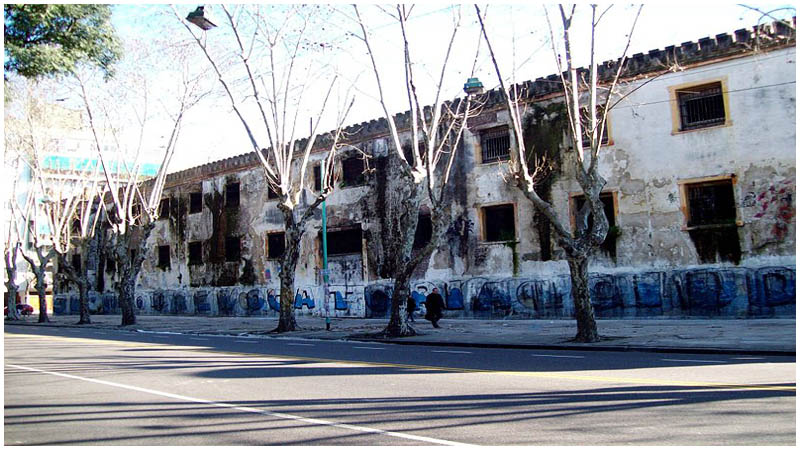

The prison continued to run until 2001, when it was closed and measures were taken for its demolition. But nothing happened for years — the empty prison stood in the middle of a crowded neighborhood and demolishing it with explosives would have been too dangerous. So it was decided that the prison should be dismantled by hand.

By 2008, much of the prison had been deconstructed and converted to rubble. In 2006 an artist by the name of Seth Wulsin used the prison as an art installation, smashing a number of windows to create pictures of faces.

“…the visual impression of 48 human faces gazing out across the city from the prison’s vast window grids. Like dark pixels on a screen, the hollows of empty window frames compose the haunting shadows of jutting cheekbones, furrowed brows and smiles” writes The New York Times in their article named Putting a human face on an Argentine prison’s history.

Today nothing remains of this prison except for photographs and stories.