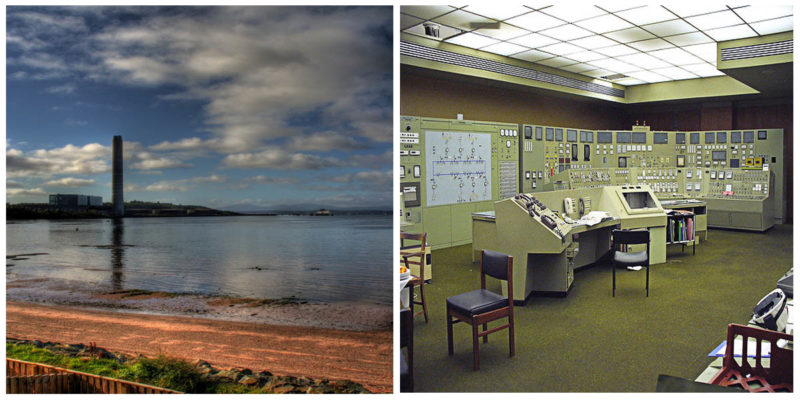

This oil-fired power station located in the district of Inverclyde had the third tallest chimney in the United Kingdom, which was also the tallest free-standing structure in Scotland.

What was different about this power station was that it had no cooling towers: unlike similar facilities, this power station used sea water as its coolant. Inverkip had in total three units for generating power, which combined produced 2028 megawatts of electricity.

Everything began in 1970 when the South of Scotland Electricity Board came up with the idea of creating Scotland’s first oil-fired power station. However, prices soared during the 1973 oil crisis and by the time construction was complete, it was already too late. The use of oil for generating electricity was no longer a financially viable move.

The irony is that during the initial phases of the construction, there were even plans for making the fourth unit. This idea was, luckily, quickly removed from thought before construction commenced.

So, the power station was never used to its full potential, perhaps being used only once at its peak capacity, during the miners’ strike of 1984-85. As supplies of the fuel for coal fired power stations began to ran low, operation of the Inverkip power station was stepped up. Most of the workers lived in Wemyss Bay and many lived in houses provided by the Scottish Special Housing Association.

Inverkip’s generation of electricity stopped in January 1988. The plan was to keep the plant as a strategic reserve, although none of these reserves were ever used. Around 18 years later, the power station was finally decommissioned and closed for good.

It was decided that Inverkip power station’s location would be turned over to serve as housing and small business development. The removal of equipment and subsequent transfer to different power stations was completed in 2006.

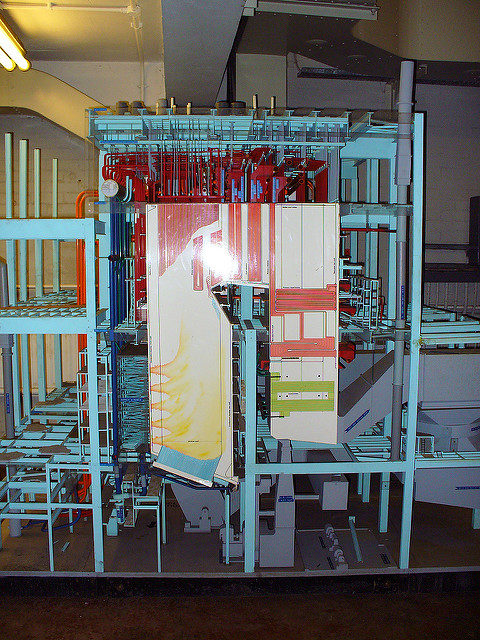

Luckily, the parts and the equipment that was used at Inverkip power station were interchangeable with some of the other power plants. For example, the main turbo-generator, manufactured by Parsons, was compatible with the generators at Hunterston B power plant located some 21 kilometres to the south.

Also, some of the turbines were interchangeable with Torness and Heysham 2 power station, and so one of the turbines was transferred to Heysham 2 Nuclear power station. This happened in the 1990s under the Central Electricity Generating Board.

The workers that worked at the power plant were transferred, one part to Hartlepool and the rest to the Heysham nuclear power stations.

One criticism given to Inverkip is that by design the power station didn’t have steam driven boiler feed pumps. And so units 1 and 2 had to be provided with three 50% electric boiler feed pumps, whereas unit 3 had received two 50% electric feed pumps.

Once all of the dangerous chemicals and electrical oil were drained, it was time for the major demolition to begin. First, one of the three major oil tanks was removed and two years later, using a controlled explosion, the demolition crew was able to bring down the main building. This happened on October 12, 2012, and by November that same year, the rest of the oil tanks were removed. Next, in 2013, the boiler room was demolished.

The final step was to bring down the chimney itself. After some productive consultation with the local railway, the police, and the local authorities, it was finally decided that the site was safe for the demolition to continue. Some final preparations and one last check of the surrounding environment was made, and the site was ready for detonation.

It was time for one of Scotland’s landmarks to pass into history. At 10 pm on Sunday 28 July 2013, the crowd who were gathered to watch first saw a quick flash of light and then a huge explosion. Like a house of cards, the chimney was no more.