The history of the Crimean Peninsula involves many different nations. Many conquerors and armies knew the importance of its central strategic position connecting Europe with Asia and close proximity with Africa.

The Ancient Greeks were probably its first colonizers (as far as our civilization knows), followed by the Romans, and then their cousins the Byzantines, who themselves lost these lands to the Ottoman Empire.

As far as modern history goes, just in the last hundred years, the Crimean Peninsula has been under the army boots of Russian Tsars, Tatars, Nazis, the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian Republic, and the Russian Federation. Today, the history of Crimea continues to unfold.

The town of Balaklava lies on the southern edge of the Crimean Peninsula. In the past century, it was neighbors with the city of Sevastopol, but Sevastopol has expanded to include Balaklava within the borders of its municipality.

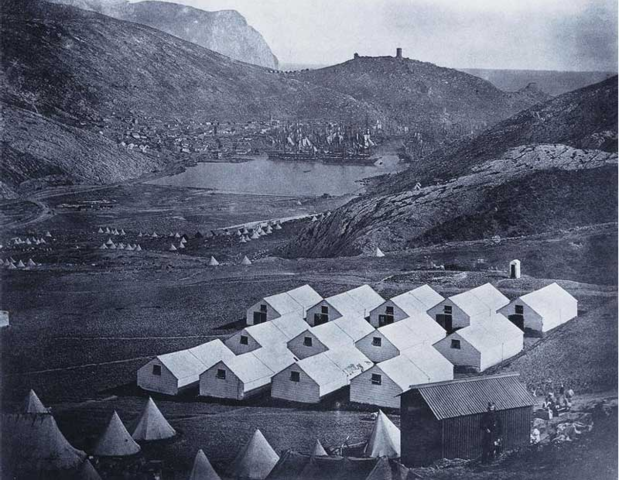

The town was named by the Ottomans when they conquered it in 1475, Balyk-Yuva meaning Fish’s Nest, and after some time it became Balaklava. Its name, Balaklava, became infamous in Europe and the Americas in 1854. It was this year on 25th of October that the most heated battle of the Crimean War, the Battle of Balaklava, took place. The last charge of the British “Light Brigade” (cavalry troop) and their doom, as immortalized by Tennyson, was part of a failed effort to take the port of Sevastopol.

The port of Balaklava has been active for centuries both as a military and civil (fishing, trade, merchant, etc.) port. But after the Cold War tensions began escalating in 1957, Stalin issued a directive to build a fleet of nuclear submarines in the Black Sea and establish a base for it.

The operation was carried out in the greatest secrecy, taking all precautionary measures they could think of remain hidden from US and British secret services. Officer Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the USSR’s nuclear project, was chosen as leader of this project. He spent years researching and scouting locations before making a final decision to choose the small, quiet town of Balaklava as a prime location.

Preparations began by securing the town, classifying the operation with the name “Objekt 825” (Object 825). The town of Balaklava was overwhelmed with engineers and construction workers of all sorts for the submarine base. All the while, outside of the town, no one had any idea of what was being constructed. Entrance to the town was almost impossible; even family members of the workers could not visit the town without hefty amounts of paperwork and extensive documents approving very short-term visitor entry limited to only a few districts of Balaklava.

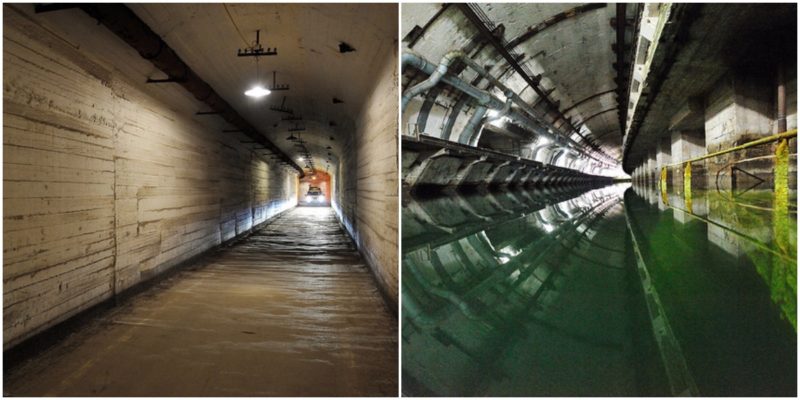

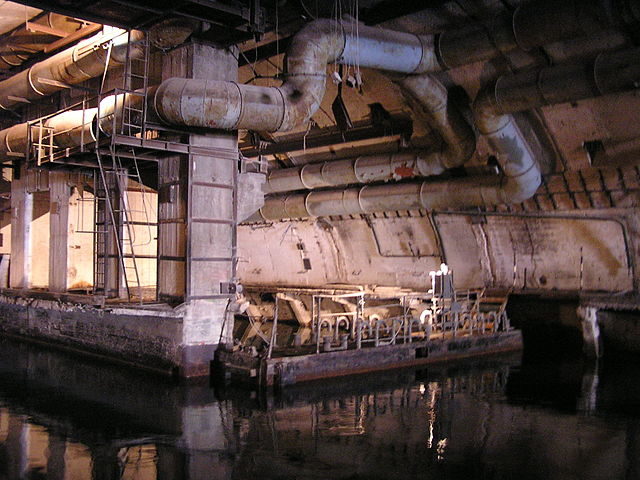

In order to create this great military giant, more than 120,000 tons of rock were dug out to form massive subterranean chambers with tunnels opening them to the waters of the Black Sea.

It took four years to finish Object 825, and when it was done, the USSR claimed the submarine base to be virtually indestructible. The secret docks and tunnels were protected by a shell of concrete and nets of steel and were capable of surviving a direct nuclear strike with the force of 100 kilotons.

The Balaklava facility survived the fall of the USSR and remained in use and functional until 1993. The next three years saw the removal of the vessels and the disarming of the nuclear warheads and torpedoes. In 1996, the last Soviet submarine left Balaklava Bay. Today, part of the base has been converted into a Cold War museum.