The oldest masonry fort in the continental United States, the 340-year-old walls of Castillo de San Marcos stand as a testament to the turbulent path of the nation to achieve unification and peace. At the time this fort was built, the territory of Florida was held by Spain.

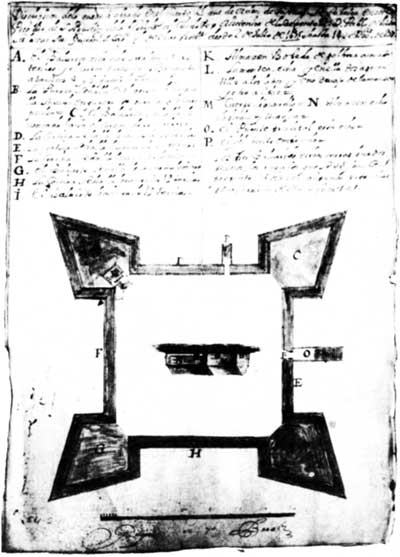

It was built in the 17th century in St. Augustine, Florida, in response to a raid led by the English buccaneer Robert Searle in 1668, as well as increasing English activity within Spanish territory. Plans were laid down by Governor Francisco de la Guerra y de la Vega to construct a defensive fortification on the western shore of Matanzas Bay which would afford protection of his city from attack from the sea, and work began in 1672 on the site of an older wooden fort under the vigilant eye of the next governor, Manuel de Cendoya. The engineer in charge of the project, Ignazio Daza, found himself faced with a problem when it came to sourcing building materials.

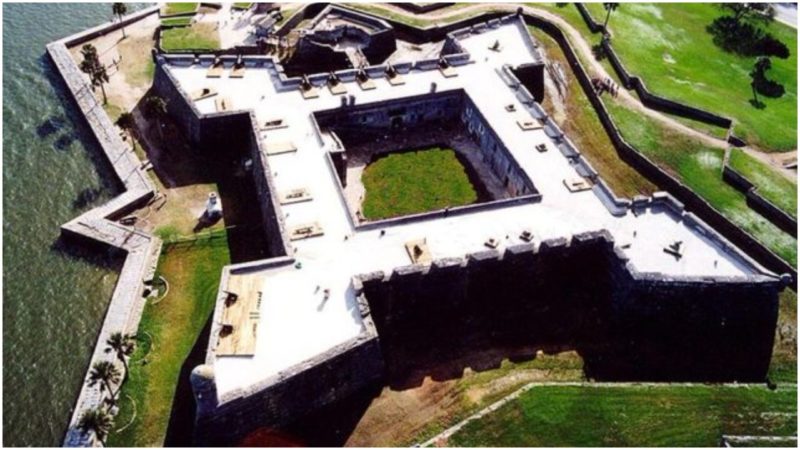

The only locally available stone was the sedimentary limestone coquina, a highly porous rock composed of large particles of seashells, which makes it challenging to work with. Unable to obtain finely grained stone such as granite that was traditionally used in such buildings, Daza made best use of what he had. He designed the fort in the classic star-shaped bastion style, with sharply angled bastions that were designed to deflect the most “modern” weapons of the day. The square design with a bastion at each corner allowed an equal view of each side, which was perfect for the flat lands of Florida.

The stone was quarried by peons, mainly low paid Hispanic and Native Americans, alongside a forced labor force of convicts, then transported by oxen, and downriver on rafts to the construction site.

One of the biggest headaches for Daza was finding enough master stonemasons to grade and work the stone. Additional skilled craftsman were hired for that purpose, and the regular workforce needed to be trained in how to create an impenetrable fortress from the seemingly delicate rock.

As work progressed and the workforce grew, food supplies became the next major problem. The agricultural system of the 17th century was insufficient to provide for the hundreds of men, so fishermen were hired to supply the workers with fresh fish and shellfish.

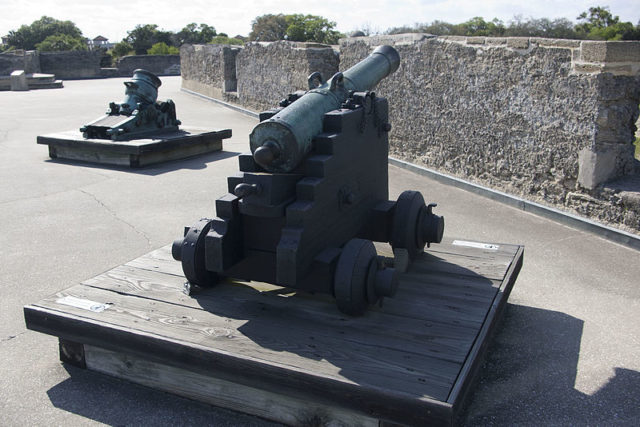

Completed in 1695, Castillo de San Marcos first came under fire in 1702, this time by English colonial forces who sailed up the coast from the recently established Charles Town (today Charlestown, South Carolina). What happened was unexpected, but brilliant. Unlike granite or brick which would shatter under the force of cannon fire, the spongy texture of the coquina meant that missiles mainly rebounded from the walls or became embedded in them. The fort, one of only two in the world to ever be built from this type of stone, truly seemed impenetrable.

The city’s 1,500 residents and soldiers were held under siege in the fort for two months until the Spanish fleet arrived to their aid. The English forces, outnumbered, burned their vessels so they weren’t captured and went on foot back to South Carolina.

A second siege by the English took place in the summer of 1740, this time lasting for 27 days, during the War of Jenkins Ear (1739-1748). The British General James Oglethorpe succeeded in blockading the river and roads into St. Augustine, but it was the low supplies of his own men that brought an end to the siege.

Castillo de San Marcos never succumbed to enemy fire, demonstrating it’s strength and endurance in a number of battles and skirmishes, but it did change hands four times by peaceful agreement. It also underwent several periods of renovation and reconstruction, and was renamed Fort Marion when Florida joined the United States.

From 1862, the fort was used as a military prison. During the Indian Wars, many Native American captives were held here, and may died here. Almost 500 Apaches were held at the fort from 1886 to 1887.

An early campaigner against racism, Richard Henry Pratt made some groundbreaking changes to the treatment of prisoners during his time as supervisor here. He allowed them to be unshackled and spend some time outside of their confined cells, as well as introducing teachers of English and missionaries to the prisoners.

Pratt would later go on to begin a program of Native American boarding schools. He believed this was a way to provide education that would improve their lives, but perversely they became places renowned for abuse and neglect.

Among the artifacts that survived the fort’s long history are a number of examples of Native American Ledger Art.

Nowadays, this place is listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places and is a U.S. National Monument.