In 1850, the first shaft was dug for coal mining in Cheratte, part of the Belgian city of Visé.

Initially, the shaft reached a depth of 250 meters (820 feet). However, engineers studied what had been uncovered and realized that the coal they sought was located further down. Consequently, the shaft was extended to 420 meters (1,377 feet).

Unfortunately, this shaft was following a seam of coal that ran alongside the Meuse River. When the mine went below the groundwater level of this river, the mine became subject to constant flooding.

To work around this setback, pumps were installed in the shaft to get rid of the water and the mine was able to continue operating. However, substantial flooding of the mine in 1877 led to the collapse of a large section of the tunnel, resulting in several fatalities.

After this disastrous incident, the owner of the mine was forced to close it and the workings remained abandoned for the next three decades.

Reopening of the coal mine

The coal mine was reopened exactly thirty years later – in 1907 – by the Société anonyme des Charbonnages du Hasard.

Because the site wasn’t very large, a decision was made to create a headframe above the shaft. This is a high tower with a hoist that acts as an elevator to allow miners to enter and leave the mine as well as transporting the rock mined underground up to the surface.

The headframe at Hasard was equipped with an extraction machine and two engines that worked on direct current. It was a first for Belgium.

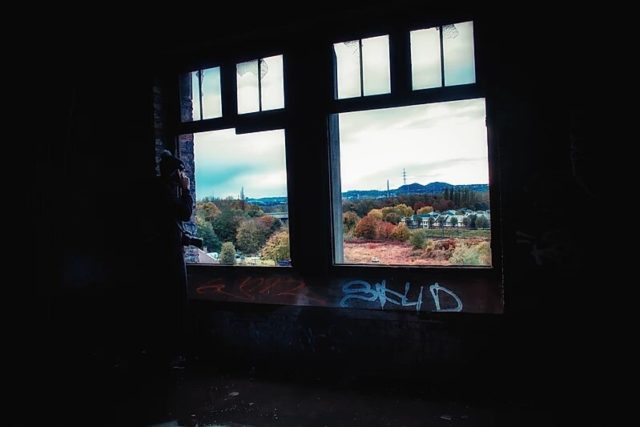

The new owners built the tower and its associated buildings in the neo-Gothic style, which gives the whole site a very distinctive look for a colliery. Some urban explorers have even described it as looking more like a church building than a mine.

In 1920, the company expanded its activities by constructing a coal processing plant and a second mining shaft with another headframe, which came to be known as the Belle-Fleur shaft. This shaft was used to bring tailings, part of the leftover material from mining, up to the surface.

Seven years later, construction began on a third mine, which lasted until 1947. By 1938, this third mine reached a depth of 313 meters (1,026 feet), but it only became operational in 1953.

The third mine shaft was gradually extended until it reached 480 meters (1,574 feet). By this point, the extraction machine at the top of the tower was insufficient to deal with the load, so the mine engineers built one on the ground which was more efficient.

While the first tower had medieval-style architecture, the second tower was metal. Since the tower associated with the third mine was the highest of them all, it was built of reinforced concrete.

In the 1950s, the first and oldest mine ceased its activities and the company instead began to use it as a rescue mine. The surrounding buildings were transformed into changing rooms and a washhouse for workers.

Records show that, in the 1930s, the number of workers at the second mine reached its peak with more than 1,500 employees. Then this number diminished until, by October 31, 1977, the mine had around 600 miners working there when it closed.

New owner and the authorities

A Flemish real estate developer, Armand Lowie, acquired the land and decided he would demolish the buildings to make way for his own project. However, he was frustrated by three state decrees published in 1978, 1982, and 1992, which were were issued to protect the facility.

In 1980, the first tower built on this site was declared a local heritage site. In 2007, the former mines and their associated buildings were included in the government’s rehabilitation program.The intention was to restore the facades and roofs as well as the machine room and the wooded hill.

The new owner continued trying to implement his plans for construction on the site. In 2008, he applied for permission to build residential houses and shops, which would have involved demolishing the concrete tower of shaft three and its associated buildings. However, he was again refused permission.

After disagreements between the new owner and local authorities lasting over 30 years, eventually Minister Philip Henry issued a notice of expropriation on April 30, 2013. After that, the plan was to open the site to the public.

The Spi, an inter-municipal company in Liège, was responsible for cleaning up the site. It was allocated a budget of EUR 2,070,000 for this task, with EUR 750,000 being needed for the expropriation and the rest to be used for the cleanup and the demolition of those buildings which were not protected.

The Spi had a master plan which it revealed in 2013, but the demolition process necessary to advance this project only began in 2017. There seem to be no new reports on how this renovation is progressing.

Thank you to Sébastien Ernest for allowing us to share his impressive photographs of the abandoned coal mine of Hasard de Cheratte. He has got not only the amazing photostream on Flickr but also a website called Spirit of Decay which you should definitely check out.

Author: Sébastien ERNEST | Flickr @bestarns

Buddhist Pagodas Lost in the Village of Indein