Deep in the heart of the Amazon Rainforest are the remains of Fordlândia, an abandoned industrial town built by Henry Ford. Intended to bypass East Asia’s monopoly over the world’s rubber supply, it wound up being a massive failure, costing Ford millions of dollars.

Establishment of a colony in the Amazon

In the 1920s, Henry Ford and his company, Ford Motor Company, were looking for a way to bypass purchasing rubber from East Asian companies, which held a monopoly over the production and supply of the material. Ford decided the best course of action was to set up a colony solely dedicated to its production, and while Central America was at first considered, the decision was made to set up shop in Brazil.

Ford was attracted to the country after hearing about the rubber trees that grew in abundance in the Amazon. To create his new town, the businessman negotiated a deal with the Brazilian government, in which he was granted 10,000 square kilometers of land in exchange for a nine percent share of the profits. Seven percent would go directly to the government, while the remaining two percent went to local municipalities.

Construction of Fordlândia

Ford’s aim was to build a prefabricated town capable of housing up to 10,000 people. Construction began in 1926, and was immediately hindered by a number of factors, including poor logistics and workers succumbing to tropical diseases, such as malaria and yellow fever. There was also no direct road access to the area, which was along the Rio Tapajós, approximately 300 kilometers south of the city of Santarém.

Fordlândia was built to mirror the amenities offered in the United States. American-style houses were built, as were a hospital, power plant, library, school, swimming pool, sawmill, three-story warehouse, golf course and a playground. As the town’s population grew, restaurants, bakeries, shoemakers and butcher shops were also erected.

Ford Motor Company sent two merchant ships, the MS Lake Ormoc and Lake Farge, to Fordlândia in 1928. The vessels carried a host of equipment and furnishings, including a 50-meter-tall water tower that was constructed in Michigan. It eventually became the town’s symbol.

Operations begin in Fordlândia

Seeking local workers, offices were opened in the nearby cities of Belém and Manaus, and before long Brazilians flocked to Fordlândia to work and reside alongside the town’s American managers. It was a tough job. Given the weather conditions, work typically began around 5:00 in the morning and ended at noon. The operation was also divided into different sections, to prevent workers from tapping the same trees successively.

The Brazilian workers were forced to live under strict rules that made it mandatory to live a “healthy lifestyle.” They were forced to attend square dances, poetry readings and English-only singalongs, and were forbidden from partaking in alcohol, tobacco use, playing football and engaging sexually with women.

They were also prevented from eating local food – instead given “Americanized” meals – and were made to wear ID badges and work under the hot tropical sun.

To ensure these rules were followed, inspectors would travel from home to home. To circumvent this, contraband was hidden on merchant riverboats and in fruit. As well, a settlement with nightclubs, bars and brothels was set up eight kilometers upstream.

Synthetic rubber and disease led to the town’s decline

It wasn’t long before Fordlândia began to experience a decline. The land was rocky and infertile, and none of the American managers sent to oversee its operations knew much about tropical agriculture. They failed to realize that rubber trees needed to be planted apart, to protect them from disease and infestation, and before long they were covered with lace bugs, ants, tree blight, leaf caterpillars and red spiders.

Another factor in the town’s decline was the Brazilian government’s suspicions of foreign investment, meaning it offered little help to Ford.

By 1930, the majority of employees began to refuse work, culminating in a revolt in the town’s cafeteria. They cut the telegraph wires and chased the managers into the jungle, where they stayed until the Brazilian Army stepped in to mediate. In the end, an agreement was reached regarding the food the workers were served.

In 1934, Fordlândia was abandoned and the town relocated to Belterra, downstream from the original location. While the conditions were better, things declined in 1945 with the advent of synthetic rubber. Due to this, Ford’s grandson, Henry Ford II, sold both towns back to the Brazilian government at a loss of over $20 million.

The Brazilian government tries to rejuvenate Fordlândia

Between the 1950s-70s, the Brazilian government, via the Ministry of Agriculture, set up several facilities in Fordlândia. The houses formally inhabited by Ford’s employees were given to the families of Ministry workers, whose descendants continue to occupy them.

Unfortunately, the project was short-lived, largely due to the lack of basic services in the area. For example, medical care could only come to the area by boat. As Ford had before, the Brazilian government abandoned the town.

Fordlândia’s population is steadily growing

While Fordlândia was largely abandoned, its population began to steadily rise, beginning in the early 2000s. In 2017, it was estimated that around 3,000 people were occupying the desolate and rundown town.

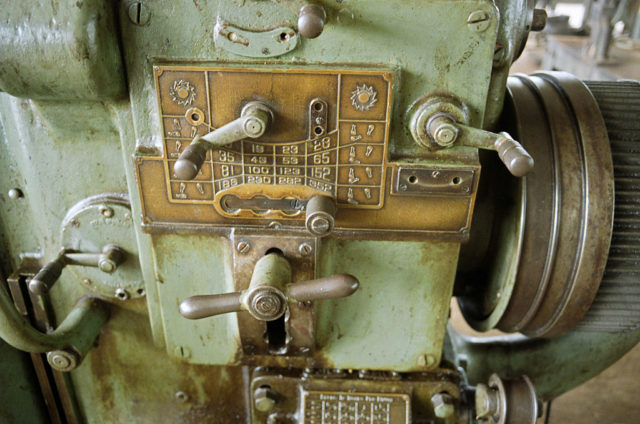

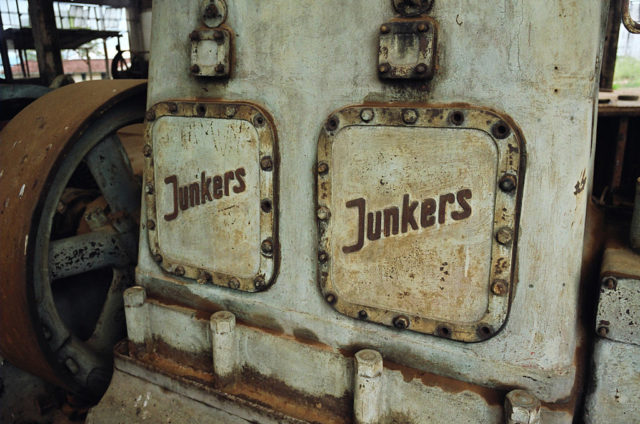

While the majority of the original buildings are still standing, they are showing signs of wear. The sawmill and its kiln are still standing, but most of the equipment is gone, and the warehouse has been turned into a storage building, housing old hospital beds, a lead coffin, various types of equipment and parts of an X-ray machine. The wooden floor on the second story has largely rotted away, leading to its collapse in some areas.

The water tower, water treatment plant and their original plumbing are still operational, and all but one of the houses in the American Village remain standing. While many were left filled with clothes, silverware and furniture, much of that has been sold by those who have since moved into the residences.

More from us: The Crystal Palace was a Symbol of Victorian England Until It Burned to the Ground

The hospital remained standing until the late 2000s, when looters removed its contents and dismantled the structure. It was the subject of intense controversy, as multiple boxes containing radioactive material used for its X-ray machines were left behind, raising fears of contamination in the area.