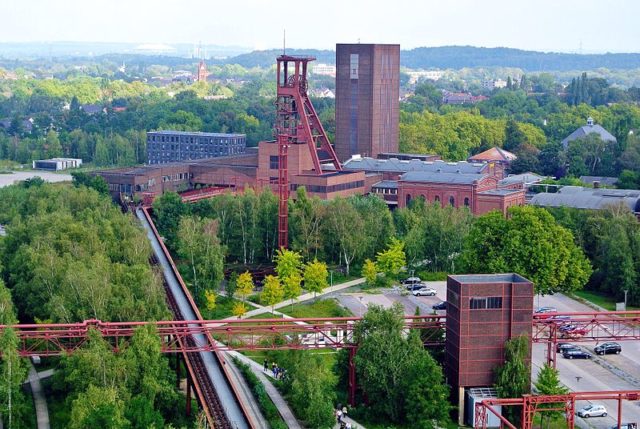

The Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex in the Ruhr region of North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany is today a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The part that remains, Shaft 12 which was opened in 1932, has been described as “the most beautiful coal mine in the world” for it’s architectural and technical mastery. Visitors to Zollverein can still see the pit head gear standing proudly above what is now a museum and heritage center.

Our journey begins hundreds of millions of years ago when the earth was dominated by swampy forests of huge fern-like plants, reeds and mosses. When these plants died, they fell into the swamp waters and, over a very long time, layers of this plant material built up. In regions where conditions were favorable, the slow geological process of turning the decaying organic matter into coal progressed. Most coal was formed between 360 million to 290 million years ago, but large deposits were also laid down in subsequent periods.

As time progressed, humans evolved and learned how to exploit the treasures that planet earth had in store for them. Among these hidden gems of nature, we discovered coal. This sedimentary rock is what is what helped propel ships, move trains, and heat boilers. It was the very basis of the industrial age, and what catapulted humanity to modern times. But for coal to be used, one must go deep into very bowels of the earth itself to find it, and this is where various mines come into play.

The initial beginnings of coal mining in the city of Essen can be traced to the 19th century in a time and age when German entrepreneur Johannes Franciscus “Franz” Haniel, prompted by his urgent need for coke to fuel his steel production, formed Zollverein Coal Mine.

A program of exploratory test drilling in the Katernberg region revealed a rich vein of coal. Inspired by what was found, Franz went on to form the bergrechtliche Gewerkschaft Zollverein corporation. Shares in the company were distributed among his family members and the owner of the land where all this coal was found.

And so the first shaft was dug on February 18, 1847, to a depth of approximately 425 feet. Pit number two was dug at the same time as pit one but wasn’t opened until 1852.

The coal was initially turned into coke fuel using methods that had traditionally been used to produce charcoal. In essence, this involved making a big, slow burning pile of coal in order to purify the carbon. The yield of coke came only from the interior of the pile. Later, modern industrial beehive ovens were introduced and the cokery output was much higher and of a better quality.

With time another shaft was dug, pit number three, and this was opened in 1883. On the verge of entering the 20th century, this mine had a staggering output of a million tons. Having such impressive results prompted the need for more shafts and so pits four and five were dug during the five years starting in 1891. Then in 1897, pit number six was opened.

But throughout years this mine suffered the same problem as other coal mines throughout the world. Where there is coal, there are usually pockets of natural gas, known as damps. Flammable gases, mainly methane, were the cause of many accidents. Underground explosions of firedamp and the toxic afterdamp gases was a serious problem that was to solved by improving ventilation throughout the mine workings. This is how shafts 7, 8, 9 came to be; new shafts that were used only for ventilation.

The first two shafts were restored and in 1914 pit number 10 was opened plus a new cokery. During World war One, the output of the Zollverein Coal Mine complex rose to an astonishing 2.5 million tons. Throughout the years, the mine was further modernized and new shafts were dug and opened. By 1937, the mine had around 6,900 employees plus 3.6 million tons of output.

The most productive of the shafts was number 12. Luckily for Germany, this mine survived the Second World War with minor damage. By 1967, 11 of the shafts were closed, leaving number 12 as the only operational pit.

In 1983, the shareholders voted to close this last working pit, and so the German town of Essen was left without a mine when shaft number 12 was shut down in 1986. After it was initially closed, the mine complex was turned into a museum offering over 6,000 exhibits, and pit number 12 became a heritage site.

Today there are guided tours into some of the former shafts as well as numerous workshops and lectures that take the visitor traveling back in time to when this mining complex was at the top of the list of most successful German mines.