Eddystone Lighthouse was erected in 1882 and automated in the 1980s. It stands on Eddystone Rocks, a small but notoriously dangerous reef in the waters of the English Channel.

The current lighthouse is the fourth (or fifth!) to stand on this site; the first one began to shine its warning in 1698. Eddystone Rocks lie 12 miles from Plymouth Sound, one of England’s most significant naval harbors, and roughly in line with the Devon-Cornwall border.

They are immortalized in an English folk song, simply called Eddystone Light, that was popularized as a folk-revival track in the 1950s by Burl Ives.

The rocks are almost completely submerged during high tide, rendering them invisible and treacherous to mariners. Being so close to the mouth of the English Channel, as well as a major port, the reef is a significant hazard that has claimed many ships.

Even though the channel is 112 miles wide at it’s west entrance, there are records of ships being wrecked on the coasts of both England and France in the days before the first light was built, because the crew were trying to give Eddystone Rocks a wide berth.

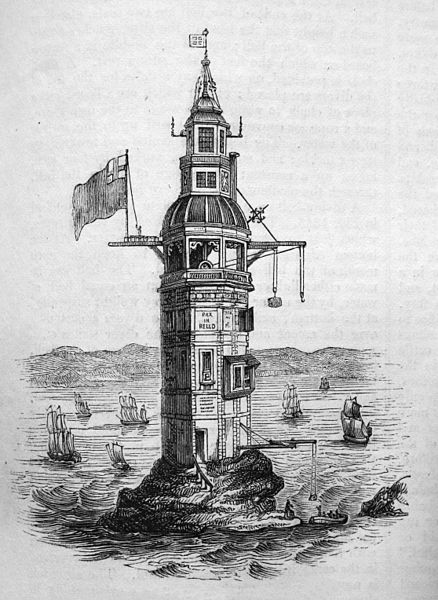

The rocks remained unmarked and difficult to navigate until the first lighthouse was proposed in the 17th century by shipping merchant Henry Winstanley, who had lost two ships to Eddystone Rocks as well as having a close encounter himself.

The original wooden structure was the first recorded lighthouse to be built in the open ocean. Construction began in 1696 and the lamp was lit for the first time on November 14, 1698.

The lighthouse survived its first winter, but suffered significant damage. It was completely remodeled into a 12-sided shape to better withstand the turbulent waters, and the wooden exterior was clad with stone. This is where the number of lighthouses is contended, as some maintain that the rebuild counts as light number two.

With its new design, Winstanley’s lighthouse stood strong for four more years. However, it was no match for the Great Storm of 1703 that swept across central and southern England on November 26 of that year, a storm which modern analysts speculate could be classified as a category two hurricane.

The lighthouse was destroyed and all trace of it vanished, as did Henry Winstanley, who happened to be in it at the time.

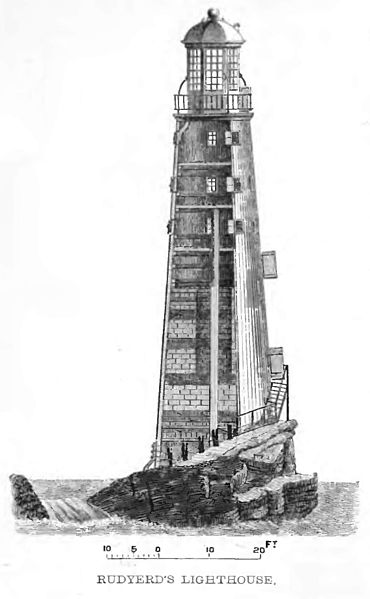

In 1708, John Rudyard designed a new lighthouse, which consisted of a concrete and brick core inside a wooden structure. Construction was completed within the year, and it managed to survive until December 2, 1755, when a lantern fire lead to its destruction, despite the efforts of the keepers to control it.

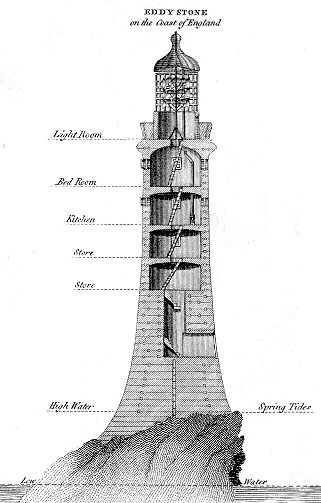

Eddystone Rocks were left, deadly and invisible, until England’s “Father of Civil Engineering,” John Smeaton, designed the third lighthouse. His pioneering design was modeled on an oak tree — an English symbol of strength and endurance. To create a long-lasting tower on the wave-washed reef, Smeaton developed hydraulic lime, an early form of quick-drying cement that would set on contact with salt water.

Construction began in 1756 and the lamp was lit three years later. Smeaton’s intricately dovetailed blocks made this lighthouse strong enough to weather any storm, but the waves did their part and in 1877 erosion of the rocks below the lighthouse caused it to shake whenever strong waves hit.

The red-and-white striped lighthouse was dismantled and taken to Plymouth Hoe, where it was rebuilt as a monument and tourist attraction.

Eddystone Rocks stood, unmarked and victorious, for the third time. Civil engineer and experienced lighthouse designer James Nicholas Douglass was chosen to devise plans for the fourth lighthouse. He chose a different rock, a few feet from the previous one, and work began in 1879.

Construction lasted for three years and in 1882 the lighthouse shone its light for the first time. The design was hard-wearing, and the lighthouse remains to this day. Standing at 161 feet, the tower renders light visible for 22 nautical miles.

Eddystone Lighthouse has become quite famous. Herman Melville mentioned it his book Moby Dick, in chapters 14 and 133. Today it is topped with a helicopter pad, making it just a little safer to access than by boat.