Bishop Rock is part of a 150 feet by 52 feet rocky ledge that rises like a sheer cliff 150 feet from the ocean floor, but much of it barely shows above the water’s surface. It holds a Guinness World Record for being the world’s smallest island with a building on it.

Before the helipad was installed on top of Bishop Rock Light in 1976, heading out in a small boat to watch the relief keepers arrive at the base of this imposing tower and being daringly winched by hand to the landing stage — 45 feet above the waterline — was a popular tourist attraction for visitors to England’s Isles of Scilly.

Located 28 miles southwest of the tip of Cornwall, the Scilly archipelago, with it’s unique climate, is exposed to the full force of the mighty Atlantic Ocean.

Getting on and off the islet was possibly the most dangerous part of the job for Bishop Rock’s keepers; as was demonstrated during filming for an episode of the iconic BBC children’s program Blue Peter in 1975. As presenter Lesley Judd was being winched up to the lighthouse, the harness of her breeches buoy broke, leaving her literally hanging on to the line for dear life. According to the BBC archive, “it looked like she was about to plunge into the murky depths.”

Despite the danger posed to shipping, the Scilly Isles for many years had just one lighthouse: The 75-feet-tall light sited on the highest point of St. Agnes island. Today converted as a holiday let, it was constructed in 1680 and is one of England’s oldest lighthouses.

Bishops Rock and it’s neighbors have claimed the lives of countless unfortunate mariners. One of the theories of how Bishops Rock got its name is that it was named after Miles Bishop, who was one of three survivors from a Spanish merchant fleet that was destroyed on these rocks.

It was on the nearby Gilstone Reef and Western Rocks where one the worst maritime disasters in British history was played out. Four Royal Navy warships, including Admiral Shovell’s HMS Association, were wrecked and 2,000 lives lost during bad weather on November 2, 1707.

But it would be many more years before plans were made to erect a warning light at the most westerly danger of the Scillies.

A report made in 1818 by the Surveyor-General of the Duchy of Cornwall to highlight the dangers to shipping off the Cornish coast concluded that a lighthouse should be built here. However, the government declined an offer by engineer John Rennie to undertake the project, and so it was dropped.

In 1834 the General Lighthouse Authority of England and Wales, Trinity House, finally carried out a survey of Bishop Rock.

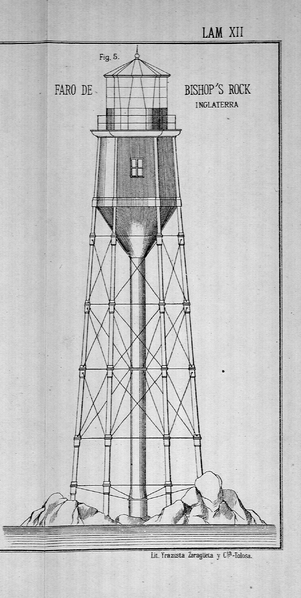

Chief Engineer to Trinity House at that time was James Walker. He chose a novel design with iron legs screwed into the rock, like a pier. Work was initiated in 1847. The tower was almost completed but, before the light equipment could be installed, the structure was washed away during a storm on the night of February 5, 1850.

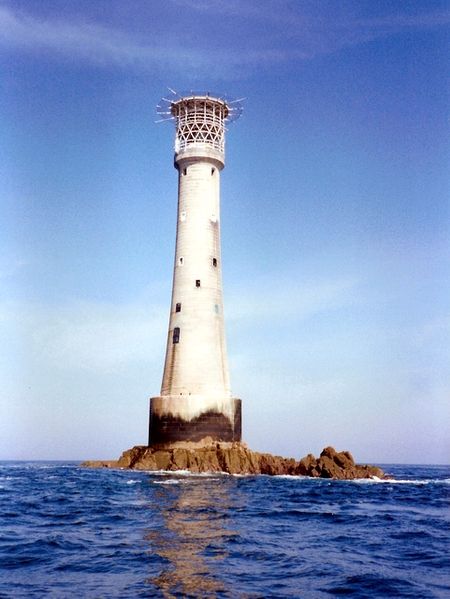

Walker began again, this time with a completely different design. It was to be a 120-feet-high granite tower based on the design of Eddystone Lighthouse. Rising from a base 33 feet in diameter, the lower part is shaped in a sleek curve to deflect the powerful Atlantic waves.

To date, storms have managed to rip off the fog bell in 1860, and on February 5, 1994, the 144th anniversary of the the destruction of Walker’s first tower, destroy the metal entrance doors. But the lighthouse itself is still standing, strong and defiant.

In conditions that would be challenging even with today’s technology and equipment, a cofferdam was put in place to allow a dry area for the foundations to be laid. The stone was shaped on another islet which was set up as a camp for the stonemasons and laborers.

Progress was slow as the builders could only work when the weather permitted. They were successful in their endeavor for no human life was lost — on September 1, 1858, the lighthouse was proud to shine its light for the first time.

Upon inspecting the lighthouse in 1881, Sir James Nicholas Douglass noted that it was time for a renovation and that reinforcing the structure was necessary. To shore up the old structure it was pretty much encased in a whole new lighthouse, and the base was strengthened.

Douglass also took this opportunity to increase its height by another 40 feet. He began this project in 1882 and by 1887 it was finalized.

George Williams, Roger Simmons and Terry Johns were the last keepers of Bishop Rock Lighthouse to be relieved from duty by boat. After they were winched down, supplies were hauled up for the last time.

The journey to work for them and all future lighthouse keepers now became a slightly less perilous helicopter ride. Bishop Rock was fully automated in 1991 — the last keepers left on December 21, 1992. It is now monitored remotely by Trinity House.

The lighthouse has famously marked the end of many “Blue Riband” transatlantic crossing challenges, including Richard Branson’s Virgin Atlantic Challenge — an award for the fastest surface-vessel eastbound crossing from New York Harbor to Bishops Rock.

The silver trophy itself is a three foot sculpture of Bishops Rock Lighthouse. Branson created his transatlantic boat challenge in 1986 after he was declared ineligible to receive the Hales Trophy because, even though his Virgin Atlantic Challenger II beat the previous record set by United States in 1952, it was not a commercial vessel.