The 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius and its impact on Pompeii has been heavily studied by historians and archaeologists over the centuries. Through excavations and scientific analysis, they’ve been able to develop an understanding of the society that sadly became buried under ash and pumice – or, at least, that’s what they initially thought.

As it turns out, recent DNA analysis has put into question long-held assumptions about the victims of the ancient Roman city.

Pompeii was situated southeast of Naples, Italy. It became completely buried following Mount Vesuvius’ eruption, with those not covered by the ash and pumice losing their lives to the lethal gases that filled the air. It wasn’t only humans who became buried – everything, from buildings and mosaics to pottery and art, became encased in the ash the volcano spewed.

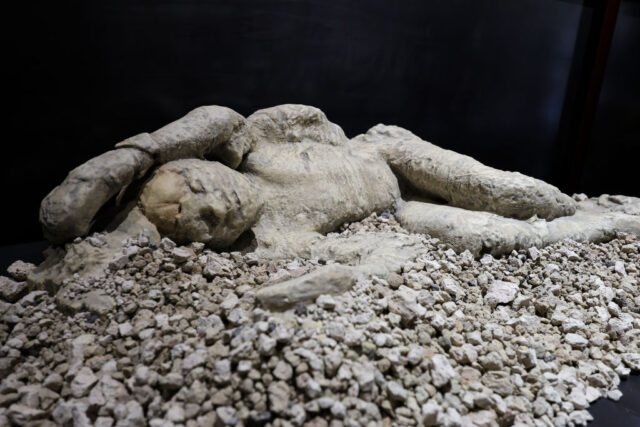

Excavations at Pompeii didn’t begin until 1748, and it took just over 100 more years for archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli to develop a plaster casting technique that allowed researchers to make casts of those who’d lost their lives in the eruption. Subsequently, the casts of 104 people were taken.

The recent findings regarding Pompeii’s victims were published in the journal Current Biology. Titled “Ancient DNA challenges prevailing interpretations of the Pompeii plaster casts,” the study took another look at the casts and found that long-held beliefs about them aren’t as straightforward as previously thought.

DNA from 14 plaster casts, collected in 2015, was examined, to identify the individuals’ ancestry, sex and genetic relationships. Among those who DNA was analyzed were:

- A mother holding a child (presumably her own).

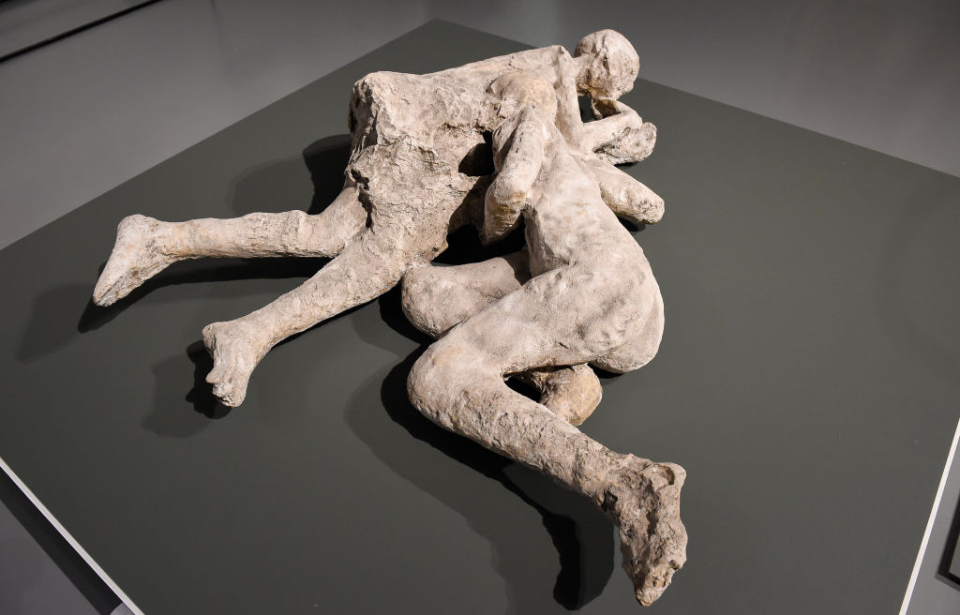

- Two women who’d held each other as they died.

- Four presumed family members who were found at the same site.

However, it turns out that the “mother” was actually a man who had no biological relation to the child, and that at least one of the two women in the second cast was actually a male. As for the other casts, it turns out three of the four family members don’t have any genetic relation – the DNA from the fourth person still has to be analyzed.

This led the team to conclude that the victims had a “diverse genomic background.”

Among the other findings revealed in the study was the makeup of those who resided in a seaside resort that was frequented by the wealthy. The team found these individuals had diverse backgrounds, with most tracing their ancestry to the eastern Mediterranean – an important discovery, as it further develops our understanding of immigration and mobility in ancient Rome.

In a media release, Harvard Medical School Professor David Reich, who co-authored the study, said, “The genetic results encourage reflection on the dangers of making up stories about gender and family relationships in past societies based on present-day expectations.”

Co-author Alissa Mittnik, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Harvard Medical School, added in an interview with LiveScience, “Our findings have significant implications for the interpretation of archaeological data and the understanding of ancient societies. They highlight the importance of integrating genetic data with archaeological and historical information to avoid misinterpretations based on modern assumptions.”

More from us: Tunic Belonging to Alexander the Great Discovered in Royal Tombs

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our Today In History newsletter!

The team behind the study was led by scientists from Harvard Medical School, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the University of Florence.