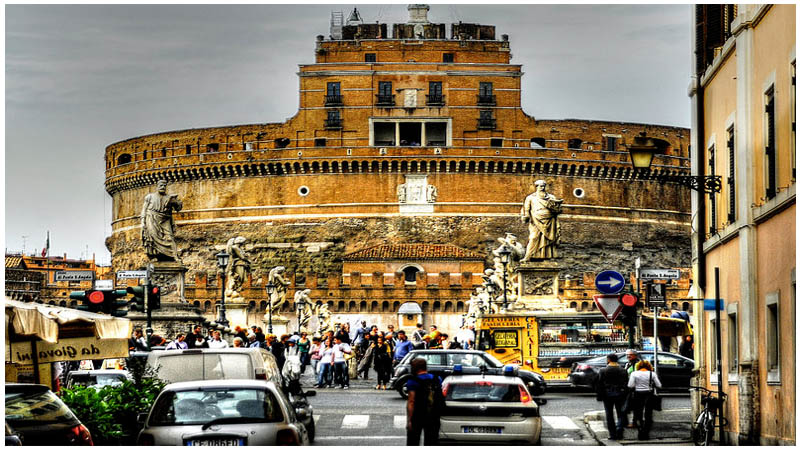

Castel Sant’Angelo is an imposing cylindrical fortress that stands on the banks of the Tiber River in the heart of Rome, Italy, not too far from the Vatican City. It was constructed over a period of five years, from 134 to 139, on the order of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (117-138) as a mausoleum for himself and his family.

The building was later converted into a military fortress and papal refuge, receiving the name Castel Sant’Angelo in 590 after an angelic vision of Pope Gregory I, which heralded the end of a plague.

The Papacy also used the castle as a prison — in fact the execution scene from Puccini’s opera Tosca is set in the inner courtyard of Castel Sant’Angelo, where capital punishment was carried out, and the heroine throws herself off the castle’s ramparts in her despair. Today, it houses the Museo Nazionale di Castel Sant’Angelo.

The tomb of Hadrian, or Mole Adriana, was indeed the resting place for Emperor Hadrian’s ashes from the time of it’s completion, and those of his wife, Sabrina, and their adopted son, Lucius Aelius, were placed there too. They were joined by the remains of successive emperors up until 217, but the urns and their contents were lost or destroyed when the city was pillaged by the Visigoths in 410.

In its early days, this structure was richly decorated. On the very top was a garden with a statue of a Quadriga, a chariot drawn by four horses abreast, made entirely from gold. Hadrian also had the Pons Aelius (Bridge of Hadrian), today known as Ponte Sant’Angelo, built to serve as a grand entrance to his mausoleum. The last emperor whose ashes were housed within the tomb of Hadrian was Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus (188-217), simply known as Caracalla.

Rome ceased to be the capital of the Western Roman Empire in 286, and the empire itself was crumbling. Rome became gradually more vulnerable but did not fall to enemy hands until the Goths, following a successful uprising against the Eastern Roman Empire (the Gothic War of 376-382), turned their attention to the once-ruling city. These Germanic tribes were being harried on their own eastern borders by the Huns and Vandals, and this pushed them to take control of territory once under Roman domination. By 493, and until 553, the Ostrogoths ruled the Kingdom of Italy.

Many the original lavish decorations that once adorned the tomb of Hadrian were lost during the 410 Visigoth sack of Rome, and the remaining bronze and stone statues were destroyed in 537 when the city was again besieged by the Goths. The mausoleum was subsequently converted into a fortress, including the addition of a defensive barbican at each corner of its square base, at some point in the 6th century.

In 590, the city was in the grip of a plague. Legend tells that Pope Saint Gregory the Great, leading a procession of penitence and prayer, had a vision in which the Archangel Michael appeared on top of the mausoleum and wiped the blood from his sword before sheathing it, signaling the end of the plague. Although this is lauded as a divine sign of salvation, some records suggest that a large proportion of the populace were worshiping a pagan idol in the belief that the older deities were more likely to save them from disease, and that Pope Gregory created a story that would bring his congregation flocking back to the Christian church.

A marble statue of Archangel Michael as he appeared in the vision, made by Raffaello da Montelupo, was placed on top of the castle in 1536. This was replaced in 1753 by Peter Anton von Verschaffelt’s bronze statue, however the marble statue can still be seen displayed in a courtyard inside the castle.

During the 14th century, Pope Nicholas III connected Castel Sant’Angelo to St. Peter’s Basilica, inside the Vatican, with a half-mile-long fortified corridor known as the Passetto di Borgo. This provided a safe passage for the pope to escape from Vatican City to the fortress in times of trouble. It was was used as a refuge throughout the Middle Ages, notably by Pope Clement VII during the sack of Rome in 1527 by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Confusingly, by this period, the title was held by the king of the Franks, and Charles V was also King Charles I of Spain and archduke of Austria at the same time. He ruled over both the mighty Hapsburg and Spanish empires, including territories in South America.

Paul III, who was Pope from 1534 to 1549 and the first Roman Catholic leader of the Counter-Reformation, decided that there ought to be a more fitting apartment to house a Pope in this fortress. He oversaw the significant remodeling of one section of the castle into lavish Papal apartments, decorated with magnificent frescoes and Renaissance paintings. From its use as a Papal residence and prison, Castel Sant’Angelo was later converted to a military barracks, still with an active prison.

Some of the most notable prisoners that were housed here were the famous goldsmith, artist, and poet Benvenuto Cellini, as well as philosopher and mathematician Giordano Bruno. Bruno, a Dominican friar, was locked up for his heretical cosmological beliefs that the stars were merely distant suns with their own orbiting planets, and his work based on the Copernican heliocentric model which outrageously suggested that the sun, and not the Earth, was the center of the universe. He spent six years of his life in this prison.

Needless to say, the prison also had a torture chamber. After it was officially decommissioned as a military fortress in 1901, Castel Sant’Angelo was restored and converted into a museum, where visitors can today see the former cells and chamber of the ashes, a large collection of Medieval weapons, and part of the Papal residence. If for no other reason, it is worth a visit to enjoy the splendid panoramic views of Rome from the rooftop cafe.