Amphitheaters were very popular in Roman times as a source of entertainment. Spectators could enjoy the experience from the comfort of their seats whilst the gladiators and animals endured intense pain and suffering.

Researchers have found indisputable evidence that although amphitheaters were primarily used for gladiatorial games, other events such as wrestling, cock-fighting, and bullfighting were also held in them throughout the Roman Empire.

Chester Roman Amphitheater is a semi-exposed amphitheater in the city of Chester, England. According to scholars, it was at first erected as a modest structure by Legio II Adiutrix, a legion of the Roman Army, when they were posted in Chester during the 70s AD.

The structure was used until the year 86, when it was rebuilt by another legion known as Legio XX Valeria Victrix (in English, the 20th Victorious Legion). The soldiers were sent off to assist in building Hadrian’s Wall in 122; when they left Chester, the amphitheater became vacant and abandoned. It was erected anew after the 20th Legion returned in 275.

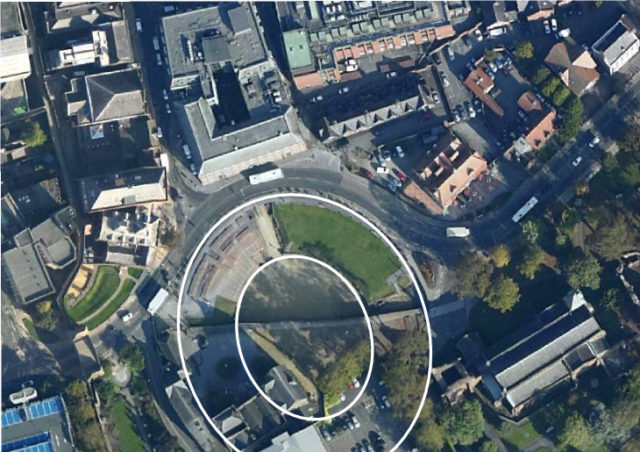

The latest version of the amphitheater was constructed using stone in the form of an ellipse. The walls were 40 feet high and the amphitheater was around 320 feet in length and 286 feet in width.

Archaeologists managed to calculate that the major axis of the ellipse ran parallel to the north-south line, and that the amphitheater had four exits and was capable of housing up to 8,000 people.

Around the amphitheater were a number of dungeons, food booths, and stables to serve the needs of the visitors. Furthermore, there was a shrine dedicated to Nemesis, the goddess of retribution, that stood at the north exit of the arena.

The size of the arena led historians to speculate that Chester could have easily become a major city in Roman times if they had managed to take over Ireland.

When the Romans left Britain for the last time and Roman rule over Britain was brought to an end, the arena fell into oblivion.

Once abandoned, the locals started to scavenge parts of the arena bit by bit until only a small portion of it was left, which was used for public executions and sometimes for bear fights.

As years went by, the area took on a different look and a new housing complex was born bearing the name of “Dee House,” which stood at the south end of the amphitheater.

At the north end of the arena, a townhouse called “St. John’s House” was constructed and thus the whole arena was lost in the passage of time. Roads were constructed that passed over the arena, although part of it was perfectly preserved underground.

The Roman amphitheater laid hidden until 1929, although its existence was speculated among historians. That same year, a long, curved wall was discovered during gardening renovations at Dee House.

The curious find captured the imagination of archaeologists and further work was carried out. When the excavation began, it was discovered that what laid hidden underground was pretty much untouched.

The only problem in the excavation was that part of it was covered by buildings. In 1939, another archaeological dig was scheduled but was postponed due to the start of World War II. In 1957, plans for the site were resumed and more excavations were done. Another idle period followed and no work was carried out until the start of the new millennium when new discoveries were made.

The arena was added to the National Heritage List for England in 1972, and featured on the BBC’s Timewatch series in 1982. Today, the site remains an area of great interest to archaeologists.