There are always two sides when it comes to the demolition of historic structures. There are those who don’t see their value and want to make room for more modern buildings, while others speak out about the loss of such beautiful architecture and the history it holds. With our ever-changing society, there’s no right or wrong answers, but the loss of these sites has us feeling sad.

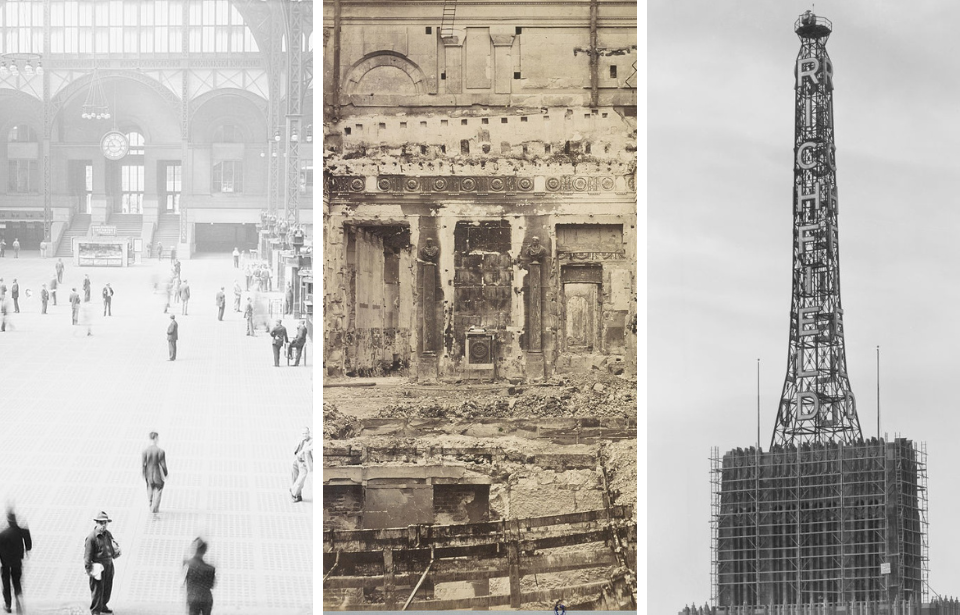

Old Pennsylvania Station – Midtown Manhattan, New York

We obviously had to kick off our list with the Old Pennsylvania Station, an icon of lost architecture. Built between 1904-10 by the Pennsylvania Railroad and designed by McKim, Mead & White, the transit hub was a premiere example of the classic Beaux-Arts design style that swept Paris in the 1800s, thanks to its large concourses and grand columns. While a place to for New Yorkers to catch the train, it never felt like a transit stop – it was as if you were taking a trip through history.

Sadly, like many of the locations featured in this article, the Old Pennsylvania Station wasn’t meant to last. With the advent of car and air travel, rail services became less in demand. Pair this with the Pennsylvania Railroad’s economic struggles and it was only a matter of time before keeping the site became unfeasible. By 1966, the building had been completely demolished to make room for Madison Square Garden and an office complex.

While New York still has since rebuilt Pennsylvania Station beneath Madison Square Garden, the transit hub doesn’t have the architectural appeal that its predecessor brought to the area.

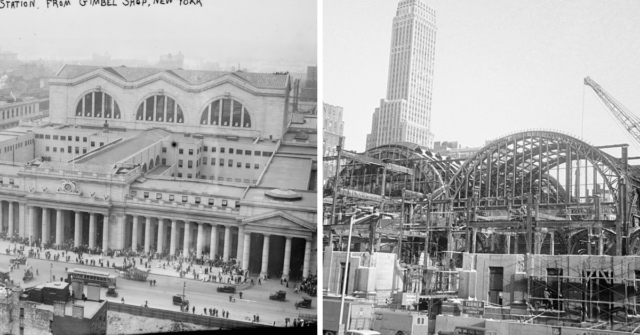

Sutro Baths – San Francisco, California

Conceived by former San Francisco Mayor Adolph Sutro, the Sutro Baths were public swimming pools fed by the Pacific Ocean. Built on the edge of the city, the complex’s seven saltwater pools were considered an engineering marvel, which made it a spot everyone wanted to visit. Capable of accommodating up to 10,000 visitors, it also featured a variety of other activities for guests, including a museum and ice-skating rink.

As tastes changed, however, the Sutro Baths found it more and more difficult to survive. By the mid-20th century, a lack of interest, paired with the rising cost of maintenance, led to the complex’s sale in the 1960s, with the plan being to replace the structure with high-rise apartments. As can be seen today, this didn’t happen, due to a fire that broke out in 1966.

Today, the remnants of the Sutro Baths sit within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, where visitors can explore what remains of the once-popular facility.

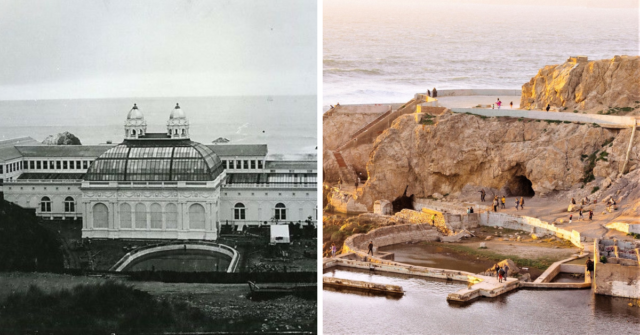

Richfield Tower – Los Angeles, California

Also known as the Richfield Oil Building, the iconic Richfield Tower was a striking Art Deco skyscraper rising into the sky over downtown Los Angeles, California. Designed by Morgan, Walls & Clements, the 12-story structure featured geometric shapes, which were paired with black and gold terra cotta to symbolize wealth (gold) and oil (black).

In 1969, the Richfield Tower was demolished and replaced with what was then known as the ARCO Plaza, an office complex that today goes by the name “City National Plaza.” While you might think a building used by an oil company wouldn’t be missed, you would be wrong in regards to this particular structure, with many in the local area expressing disappointment over the loss.

Crystal Palace – London, United Kingdom

Originally constructed to host the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, United Kingdom, was one of the city’s many beautiful Victorian structures. Designed by Sir Joseph Paxton, it was unique in that it was constructed primarily of iron and glass, bringing its name to life.

Given its purpose, the Crystal Palace was built across a large swath of land. Covering 990,000 square feet, it remained in Hyde Park until 1852, when the process began to relocate it to Sydenham Hill. The effort took just two years, quite fast by standards from that time, and it became one of the most popular locations around.

Sadly, a fire broke out at the site in November 1936, completely devastating the structure. It took 400 firefighters to put out the blaze, and while it was extinguished within a matter of hours, the damage was done. With just two of its magnificent towers still standing, the decision was made during the Second World War to demolish what remained.

Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel – Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City‘s Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel was among the most extravagant resorts on the American East Coast. Built in 1902 by Josiah White III, it screamed elegance with its Moorish Revival architectural style that attracted some of the country’s wealthiest; it featured turrets, domes and intricate details, making it a popular spot among those visiting the coast of New Jersey.

However, all good things much come to an end. When the bubble burst on Atlantic City’s boom, so, too, did the hotel’s appeal. A decline in clientele meant not enough money was being brought in to keep up with maintenance, and the development of newer casinos in the area resulted in it no longer being the go-to spot for those looking to have a good time.

In 1978, the Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel was demolished, to make way for the Bally’s Park Place Casino.

Nergal Gate – Nineveh, Iraq

The oldest structure on our list, the Nergal Gate served as the entrance to the ancient city of Nineveh, in modern-day Iraq. Built in the 7th century BC during the reign of Sennacherib and named for the Mesopotamian god of war and the underworld, it was truly a masterpiece, with statures of winged bulls “guarding” its entrance.

Sadly, the Nergal Gate couldn’t survive the ongoing unrest in the Middle East, with militants destroying the structure in the mid-2010s. This was just one of many incidents where groups have tried to erase Iraq’s historical and cultural heritage.

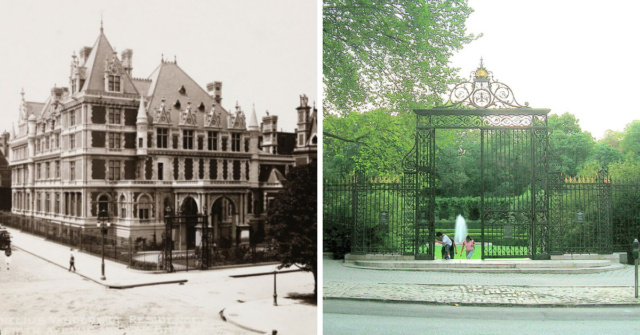

Cornelius Vanderbilt II House – Manhattan, New York

The Cornelius Vanderbilt II House, built for the prominent American socialite of the same name, was one of the most opulent private residences in Manhattan, New York, during the late 1800s. Designed by George B. Post and Richard Morris Hunt with gilded age architectural style in mind, the structure became the focal point of Millionaire’s Row.

Unfortunately, Vanderbilt didn’t get to ensure the mansion for long, as he died a mere six years after its construction. As the area began to transition from being a residential neighborhood to one centered around business, the socialite’s widow, Alice, made the decision to demolish the home, as developers were chomping at the bit to purchase the land upon which it sat.

Following its sale in 1926, the Cornelius Vanderbilt II House was demolished and replaced by the Bergdorf Goodman Building.

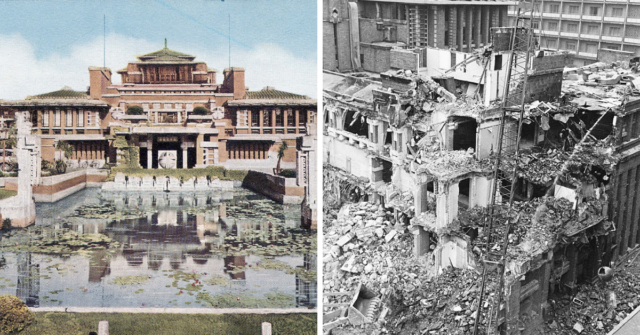

Imperial Hotel – Tokyo, Japan

The Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan, was once a landmark that not only symbolized Japan’s modernization, but also the classic architecture of the early 20th century. Designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, it featured a blend of Eastern and Western styles, with an emphasis of the Mayan Revival style that was growing in popularity around the time.

Unlike many of the structures around it, the Imperial Hotel managed to survive the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923. However, it sadly couldn’t avoid the country’s rapid modernization and urbanization efforts. With many viewing its design as outdated, it was decided that the structure would be torn down and replaced with a newer, more modern hotel.

While most of the original Imperial Hotel was lost during its demolition in the 1960s, parts of it, including the lobby, were saved by the Museum Meiji-Mura, where they can be viewed today.

Chicago Stock Exchange – Chicago, Illinois

While the Chicago Stock Exchange may be a little underwhelming nowadays, the original building was a work of art. Built in the late 1800s, it rose into the sky as a symbol of the city’s booming economy, its massive arched windows, ornamental terra cotta motifs and vast trading hall telling the world that Chicago was a major player in the economic sector. It was designed by Adler & Sullivan, with Louis Sullivan lending his artistic talents to the mosaics that covered its walls.

Similar to the Imperial Hotel, by the mid-1900s the Stock Exchange was looking a bit dated, leading to its demolition in 1972, to make room for a more modern structure. This, understandably, sparked outrage, with many calling out the loss of such an iconic landmark. This allowed for parts of the building to be salvaged, including the arch that stood over the entrance. It can be found standing outside of the Art Institute of Chicago.

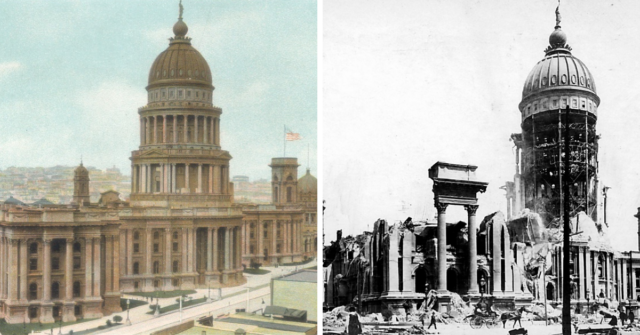

Original San Francisco City Hall – San Francisco, California

The original San Francisco City Hall building was another example of the popular Beaux-Arts style of the 1800s. It was designed by Arthur Brown, Jr. to feature a dome that, at the time, was one of the biggest in the world. This, paired with its ornate façade, made it a physical symbol of the city’s prosperity.

Unfortunately, just like the Crystal Palace, the building was destroyed by a devastating fire – in particular, those that were sparked following the devastating 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. Caused by ruptured gas mains, the blaze caused extensive structural damage, ultimately leading to the collapse of not only its iconic dome, but much of its upper structure; there wasn’t much left that could be saved.

Not a city to let such a devastating event define them, San Francisco worked hard to bounce back after the events of 1904. A new City Hall building opened its doors in 1915, and while not as grand as its predecessor, it’s still a sight to behold.

New York World Building – Manhattan, New York

Rising high above the Civic Center in Manhattan, the New York World Building was once home to the newspaper of the same name. Commissioned by publisher Joseph Pulitzer, it rose over 300 feet into the air, making it the world’s tallest building.

Completely in 1890, the structure only survived until 1955, when it was demolished to make room for the expanded entrance to the Brooklyn Bridge. By that time, New York World had merged with the New York Telegram. While most of it was lost during demolition, some parts of the building were preserved; its cornerstone and a stained-glass window are currently at the Columbia University School of Journalism.

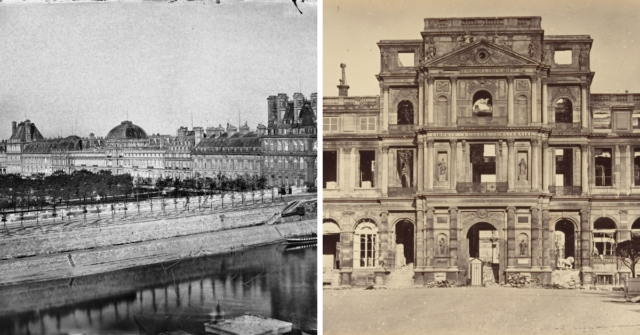

Tuileries Palace – Paris, France

Constructed in 1564 by order of Queen Catherine de’ Medici, Tuileries Palace served as a major royal residence in Paris, France, for centuries. Erected adjacent to the Louvre, it housed many notable figures, including King Louis XIV.

As a result of the upheaval that occurred during the French Revolution, the palace was seized, with it later becoming the official home of military commander Napoleon Bonaparte upon him becoming the emperor of France. Fifty years after his death, amid what became known as the Paris Commune, the building was intentionally set ablaze, and while there were attempts to restore what remained, the decision was ultimately made to raze the remnants.

More from us: 30+ Photos of Abandoned Olympic Venues That Were Left to Rot After the Games Were Over

All that remains of the once-royal site is the Tuileries Gardens, which continue to serve as a reminder of what was once one of the grandest structures in all of Paris.