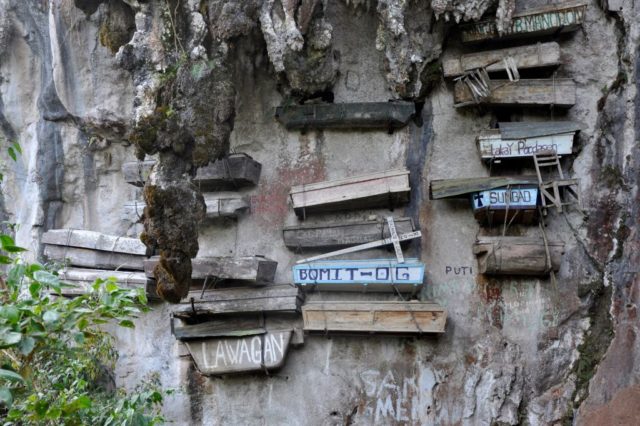

Located north of Manila in the Philippines is the mountain municipality of Sagada. While not known for its tourist industry, the area has become something of a destination over the past couple of decades, with visitors lining up to view the coffins that hang off the side of cliff faces. What many might not realize, however, is that the practice is integral to the local people’s funerary traditions and has a history that spans millennia.

An East Asian funerary practice

While many in Western culture might not be aware of the practice of hanging the coffins of the dead, it’s a funerary practice that’s occurred in many East Asian countries – in particular, the Philippines, Indonesia and China. To better appreciate the sight, one must first develop an understanding of the practice’s history and why different cultures opt to honor their dead in this way.

In China, the custom was largely used by the ancient Bo people, who inhabited the areas of Yunnan and Sichuan. As the Bo are now extinct, historians have been unable to determine the purpose of the hanging coffins. However, it’s believed they were placed at such heights to prevent the dead from being disturbed.

It should be noted that the funerary practice was not limited to the Bo, as other hanging coffin sites have been discovered across China, all of which date back to different time periods.

In Indonesia, the Toraja people of South Sulawesi use hanging coffins for either primary or secondary burials. These coffins, known as erong, have a distinct appearance and are carved into the shape of a boat. They are hung below the cliff-face, and while the majority are placed near cave openings and natural overhangs, others sit beneath manmade ones.

Of particular interest is that the coffins are guarded by wooden depictions of the dead, known as tau-tau. The intention is to ward away looters who might steal the items placed alongside the dead in the coffins.

The hanging coffins of Sagada

The hanging coffins of Sagada are among the funerary practices of the Indigenous Kankanaey people, who inhabit the island of Luzon. The coffins are typically reserved for those of a high social status – the most prominent members of the amam-a, a council of male elders – and the height at which they’re placed reflects this.

As the coffins have not been studied by archaeologists, their exact age is unknown. However, the practice has been around for over 2,000 years. It is common for elders to carve their own coffins out of hollowed logs and for their families to perform the task if they are too weak or ill.

The coffins are placed beneath natural overhangs in the cliff-face and are typically held in place by rope. Given this, it is common for them to deteriorate and fall from their positions.

The reason the coffins are hung off cliff-faces is due to the belief that the higher the dead were placed, the more likely their spirits are to reach a higher nature in the afterlife. They also feel it ensures their spirits can continue to protect the living. The deceased are also placed inside the coffins in the fetal position and wrapped in a blanket, as it’s a Kankanaey belief that one should leave the world the way they entered it.

Prior to being placed in the coffin, a number of pre-internment rituals known as Sangadil must be performed. This includes the butchering of pigs and chickens for community celebrations. While tradition dictates two chickens and three pigs must be slaughtered, those with less money may only butcher one pig and two chickens.

The deceased must also be tied to a wooden chair – known as the “death chair” – with vines and rattan. Once secured, they’re covered with a blanket and placed within their home, with the chair turned to face the main door. Relatives are then allowed to visit and pay their respects, while the body is smoked to delay decomposition.

It is only after these rituals have been performed that the deceased can be laid to rest.

While once a storied tradition, the practice of hanging coffins is beginning to fade into history. This is because the younger generation is opting to have their loved ones buried in cemetery plots, so they can visit them on All Saints’ Day, during which Christians and Roman Catholics honor the lives of saints.

More from us: The Legacy of Uruguay’s Abandoned Anglo Meat Packing Plant

Today, the hanging coffins have become something of a tourist attraction for those visiting the Philippines. Travelers are asked to not touch or walk beneath the coffins and are reminded to be respectful, as the coffins do contain the local community’s dead.