The complex formerly known as Chao Ponhea Yat High School in Cambodia was named in honour of an ancestor of Norodom Sihanouk, who was twice King of Cambodia and also led the country as prime minister and as president during his lifetime. A place for educating the young was one day, all of a sudden, transformed to a place of horror.

The conversion itself took place in 1975, the same year the Civil War of Cambodia ended and the communist Khmer Rouge seized power, declaring victory and setting in motion their plan for the punishment of all those who opposed them. As part of their method to suppress resistance, the school system was abolished, and anybody deemed to be educated or who demonstrated critical thinking was locked up, most likely interrogated and tortured.

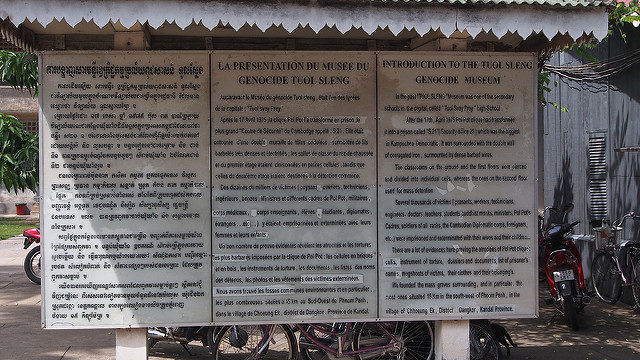

The modern and once-carefree three-story school campus nestled in a quiet neighborhood was turned into an interrogation center and prison which the Khmer Rouge named “Security Office 21 (S-12).” It became more commonly known as Tuol Sleng, meaning “poisonous hill.”

First, they enclosed the perimeter of the school with electrified barbed wire, and the classrooms were converted into torture chambers or prison cells. The windows were closed off with tough prison bars and even more barbed wire.

Once completed, Toul Sleng held from 1,000 to 1,500 prisoners at a time, with up to an estimated 20,000 people being processed through this torture center between 1975 and 1979 as part of the Cambodian Genocide Project.

The mechanism for processing these prisoners was simple; they would be subject to torture and harsh interrogation until they signed a “confession” and, willingly or unwillingly, revealed the names of his or her family members or associates as co-conspirators against the regime. After giving their confession, the prisoners were bound and transported by truck to Choeung Ek — aka the Killing Fields of Cambodia — where they were brutally killed and dumped into mass graves.

The prisoners of this institution were part of the regime of Pol Pot and his supporters, who controlled a large part of Cambodia, which they renamed the Democratic Kampuchea state, through fear, forced labor, torture, and genocide. A great many Cambodians found themselves on the hit list; from students, teachers, and academics, to doctors or engineers. Former soldiers and government officials of the defeated Lon Nol’s Khmer Republic, as well as their relatives, were literally hunted down, as were those accused of being political activists

Even communist-oriented politicians of the highest order, who seemed to be in safe positions within the Khmer Rouge organisation, were not immune to persecution. Examples include Hu Nim, the Minister for Information from April 1975, who rewrote his confession that he was a “counterfeit revolutionary” several times after his arrest in April 1977 until his execution in July 1978; and deputy prime minister of Democratic Kampuchea, Vorn Vet, who was also killed in 1978. Both were held and tortured at Tuol Sleng.

The routine for admitting the newly arrived followed a certain pattern and included photographing the prisoners, after which they were required to divulge their whole life in a form of an autobiography.

Then they were relieved of everything they carried with them at the time of their arrest and were subsequently sent to their prison cells. Inside these small confinements, the inmates were shackled to the wall. The prisoners were checked upon daily to see if they might hide an object that would be sufficient enough for them to take their own life.

The inmates had no choice but to lay on the bare stone-cold floor. As if the torment wasn’t enough, they were forbidden to communicate with one another and were fed only small portions of rice and water that resembled a soup; they needed permission from the guards simply to drink water.

The torture process was designed to force the prisoners to admit whatever he or she were accused with. It included gruesome methods, such as poking with searing-hot metal pokers, partial hanging, plastic bags for asphyxiating were placed over the heads of the inmates to a point of blackout, neat alcohol poured over massive open gashes, waterboarding, and pretty much everything a malicious brain can come up with. According to the Daily Mail, “The most difficult prisoners were skinned alive.”

The dreadfulness of this place continued until 1979 when S-21 was located by the Vietnamese Army. Only one year later, this horrid place was converted into a museum, bearing testimonies of the Khmer Rouge’s horrific rule. Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum stands as a reminder that the unthinkable really can happen.