In 1610, King James I of England gave out an order under the Bridewell Act that every county under his rule must have a jailhouse. Shepton Mallet in Somerset had no such institution prior to this date.

In order to fulfill the king’s orders, land was purchased from the Reverend Edward Barnard, and a jailhouse known as Cornhill was officially opened and readied to receive its first inmates.

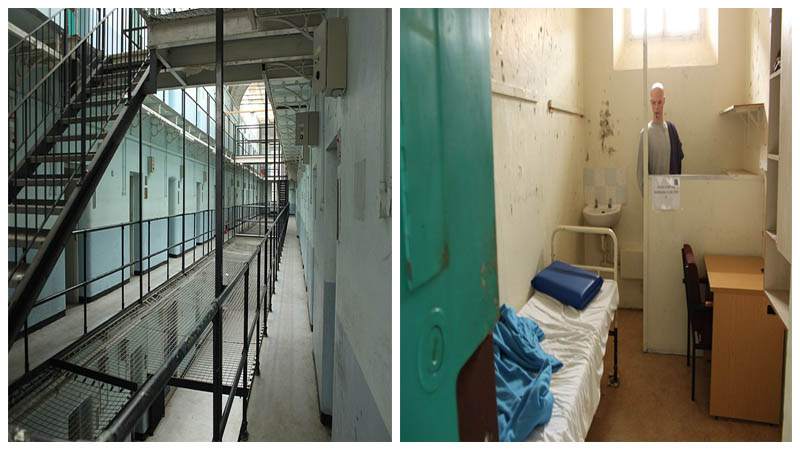

Men, women, and even children were all locked up together in no particular order. They were kept inside small cells that reeked of urine and were often infested with smallpox.

On top of it all, the prisoners were often left to starve – as if the horrendous environment in which they were kept wasn’t a strong enough punishment in its own right.

At first, the prison housed all sorts of offenders – from small-time crooks, debtors, and misfits all the way to murderers and people who were mentally unstable and ill.

Back in those days, only minimal records were kept. The number of people who could read and write was relatively small, and this is the main reason Cornhill’s early years were left almost undocumented. With no written rules, the jailers often drank and hassled the inmates.

These jailers were not on what we might now call a typical payroll: they received no wage for their services but instead made their living by selling different things to the inmates – like alcohol, for instance.

For years, conditions in the prison remained unchanged and even worsened. It wasn’t until 1773 that an official inspection was made.

According to the commissioner John Howard, prisoners were “seen pining under diseases, expiring on the floors in loathsome cells, of pestilential fevers, and confluent smallpox.”

The prison did have one doctor, although their only role was to officially pronounce death. After this was proclaimed, the inmate’s body was taken to the prison graveyards and was often placed into an unmarked grave. The burial ground still survives to this day.

The prison was also notorious for its death sentences, which were carried out in a rather brutal way. For instance, after the Monmouth Rebellion – which lasted between 1642 and 1685 – had ended, 12 rebels were executed. They were decapitated, and their heads were placed on poles around the town to serve as a warning.

The practice of execution continued over the centuries, and the last man to be executed at the prison was John Lincoln, who was hanged in 1926 for killing one Edward Richards on December 24, 1925. Edward was 25 years old when he was killed.

Four years after Lincoln was hanged, the prison was closed due to being insufficiently used. There were on average only 51 inmates during this period. It remained closed for nine years.

It was put back to use in 1939, but this time it served as a military prison. During World War II it served as an American military prison, and the number of prisoners climbed to almost 800.

The death sentence was once more utilized, and 18 more people were killed – two of whom were executed by firing squad.

Once the war was over the site was given back to the British, who continued to use it for military purposes. It wasn’t until 1966 that it was converted for civilian use. One year later, the room where the gallows once stood was re-purposed as the prison library.

HMP Shepton Mallet remained fully functional until it was closed in 2013, after 400 years of service. Rumors of the site being haunted then started to surface.

After its closure, prison officers reported finding staircases that seemingly led to nowhere and a number of tunnels underneath the complex.

Another Article From Us: Bodmin Jail and Its Famous Gallows That Took the Lives of 32 Inmates

They also found windows that were bricked up for some reason, but due to lack of documentation, this reason remains a mystery. The site was opened to the public in 2018 to serve as a tourist attraction, and the prison building is Grade II listed.