Located in the remote district of Mirdita, Spaç Prison was among the most notorious places of detention in Albania, if not Eastern Europe. Constructed to house political prisoners, the surrounding area was so sparsely-populated that the government didn’t feel a need to construct a wall around the site – barbed wire was all that was needed to keep inmates from escaping.

Construction of Spaç Prison

The construction of Spaç Prison occurred during the early-to-mid 1960s, with Albania‘s Communist leadership aiming to model it after the gulags erected in the Soviet Union under the reign of dictator Joseph Stalin. The remote complex combined the country’s two prison styles: forced labor and isolation.

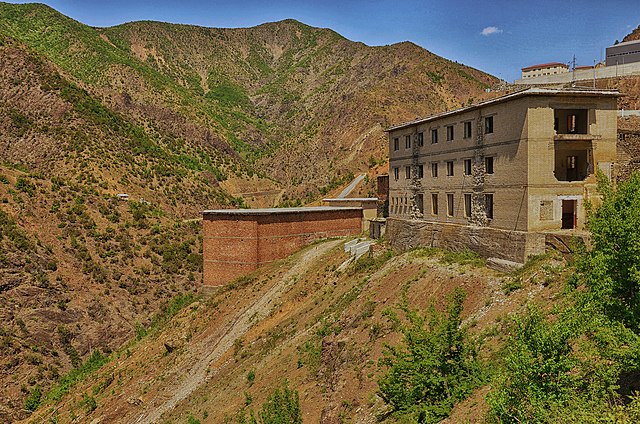

The two cell blocks and multiple support buildings that made up Spaç Prison were constructed along the terraced slopes of north-central Albania. Just outside of the main complex was the command building, and further down the path were two tall towers that housed prison and mine workers, as well as their families.

Housing Albania’s political prisoners

Spaç Prison opened in 1968 and quickly became known for housing some of the 20th century’s most prominent intellectuals. The prisoners were housed 54 per cell, and all were made to sleep on three-tier bunkbeds with bedding made from hay. When it came to food, their rations were poor and far less than what was needed to sustain them.

Everyone held at Spaç Prison was forced to work in the mines that dotted the rugged landscape. There were five mining zones, in which inmates worked long hours in grueling conditions. Reports state the heat reached up to 40 degrees Celsius and that everyone working underground had to contend with toxic fumes and dust. On top of this, shaft collapses meant some prisoners were shut off from the world for days at a time.

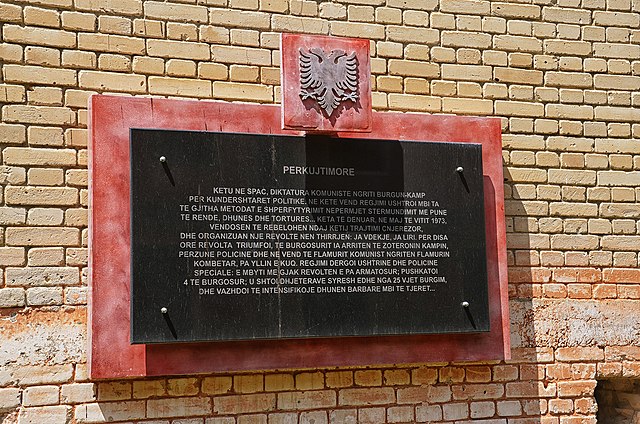

From May 21-23, 1973, the inmates staged one of the first resistance actions against Albania’s Communist regime. They protested against their inhumane working conditions and the suppression of the country’s liberalizing movement, and showed their dislike for Communism by raising the non-Communist flag.

Spaç Prison continued to operate as a labor camp until the Communist Party fell from power in the early 1990s. A few years later, the complex was completely abandoned.

Efforts to keep Spaç Prison standing

At present, Spaç Prison stands in ruin after suffering years of destruction, neglect and looting. Additionally, a private mining company led to the destruction of barracks that were subsequently replaced with newer buildings designed to aid in the mining activity.

In 2007, the Albanian government declared the prison a Monument of Culture, and efforts were made to convert the complex into a museum. However, nothing came of this. In 2016, the Ministry of Culture named the site a “protected area,” and this was followed a year later by emergency consolidation work by CHwB Albania, with support from Sweden. While this was ongoing, efforts were being made to collect a detailed history of the prison.

In 2015, World Monument Fund, an organization based out of New York, listed Spaç Prison as one of the 50 most endangered monuments in the world, due to the amount of deterioration it’d suffered since its abandonment. Four years later, CHwB Albania, with the assistance of a team from Worcester Polytechnic Institute, created a 3-D reconstruction of the complex.

More from us: The World’s Largest Aircraft Boneyard Is Located In the Arizona Desert

Since its closure, Spaç Prison has served as a grim reminder of the brutal treatment prisoners suffered under the country’s cruel Communist dictatorship, with cell walls featuring etchings of names and various images. In fact, it’s become so notorious that many Albanians use the site’s name as a metaphor for those who endure punishment under the country’s judicial system.