Who knows how many stories filled with sorrow and joy lie buried beneath forgotten and ruined structures, especially if such once-thriving locations in the distant past were strategically important and the main scene of great and turbulent events that changed the course of history.

Archaeologists and historians with methodical work can discover the significant facts and uncover the main protagonists, but sadly, this rediscovering is only a glimpse of the original stories. The essence of the true narrative and the unknown actors will always remain lost in time.

Fortunately in such cases there is another, brighter, side of the coin. Some sites that were abandoned a long time ago have had the fate throughout the years to be overgrown with lush vegetation and to become one with nature. This amazing fusion has unspeakable power to boost people’s imagination and in some mystical way to bring back to life the ruins and fragments of the stories that are connected with them.

The picturesque ruins of Alūksne Castle, initially also known as Marienburg (St. Mary’s Castle), are nestled on Castle Island (or St. Mary’s Island), the biggest of the four small islands in Lake Alūksne, near the shore of the town of Alūksne in the northeast of Latvia.

Throughout the centuries, especially during the medieval period, the region went through turbulent geopolitical changes. As a consequence of its strategic position, many neighboring empires and their rulers fought against each other for this important location. The castle was controlled in turn by Russians, Poles, and Swedes.

The name of Alūksne was first mentioned in written documents in 1284, in the Chronicles of Pskov. But the castle was constructed in 1342 by the orders of the Landmeister Burkhard von Dreileben. He was master of the Knights of the Livonian Order (a branch of the Teutonic knights). The fortress was erected as a crucial part of the defense system of the eastern borderline of Old Livonia. During the same year another significant castle was built in the neighboring area of Vastseliina. The defense line was built in an effort to stop Russian attacks from east, primarily from Pskov and Novgorod.

It was consecrated and officially put in function on Annunciation day (25th of March), the feast that celebrates the visit of the archangel Gabriel to Virgin Mary, when he told her that she would give birth to Jesus Christ. Probably the castle got it’s original name in honor of the Mother of the Son of God. But some think it acquired its name after a tragic and bizarre event that supposedly happened in the past. According the legend that is still remembered and told by locals, a girl named Maria was walled in the foundations of the castle.

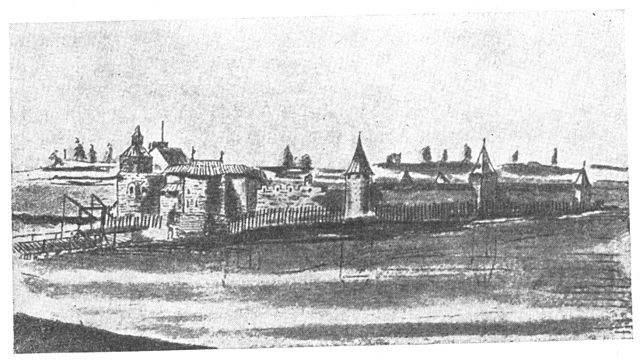

At first the castle was built predominately of wood, but very soon it was acknowledged that it cannot survive strong attacks. Later, especially during the political turmoils at the beginning of the 16th century, it was reinforced. The outer defense walls were built from local stone used in its natural form, and the convent building, which had a well strengthened adjoining flanking tower, was made of bricks. The main gate with its two circular towers was probably built in the same period.

In the 16th century the castle survived many attacks, but parts of it needed to be reconstructed several times. It was finally captured by the Russian armed forces led by Ivan the Terrible in 1560 during the Livonian War. At the end of the 16th century, the area and the castle became part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and in 1629 Alūksne was integrated in the Swedish Empire.

After the collapse of Old Livonia, Alūksne Castle was still suitable for residential use. The Swedes considered it very important for their empire and made plans for a complete remodeling. Probably they intended to stay there for longer. But a great part of it was torn down in 1702 during the Great Northern War, when was deliberately destroyed by the Swedish troops that controlled it, in order to avoid the capture of this mighty stronghold by the Russians.

After that the castle was abandoned and entered in a process of slow decay. It didn’t meet the requirements of a military base for modern warfare, but also the area lost its strategic importance. Now there can be seen the remains of few walls approximately 16 ft high, parts of towers, and a lot of piles of rubble scattered around and overgrown with vegetation. Parts of the site, which is open for public visits, were systematically excavated, preserved and reconstructed from 1977 until 1980.