The Clink gaol served an area on the south bank of the River Thames, known since the 14th century as the Liberty of The Clink, which is now a part of the London Borough of Southwark.

The term “Liberty” dates from Medieval England; it denotes an area that was privately owned by a feudal lord, from which he pocketed any revenue, and was not under the jurisdiction of the Crown. The lord was free to set his own laws within his Liberty.

The prison was built by Henry of Blois, who was appointed Bishop of Winchester in 1129 by his brother, King Stephen of England.

After also receiving a commission as papal legate in 1139, Henry became the most powerful man in England after the monarch. He gained ownership of the liberty that he named the Liberty of the Bishop of Winchester circa 1144-1149.

While the diocese of the Bishop of Winchester was in the county of Hampshire, his domain extended much further than these boundaries.

He also had responsibilities as a member of Parliament’s House of Lords. Keen to create a grand residence close to Westminster that would reflect his wealth and status, Henry de Blois ordered the construction of his own manor.

Visitors to London today can see the remains of Winchester House — just one small corner of the Great Hall with its iconic rose window. The estate was vast and within its borders there were two prisons, one for men and the other for women.

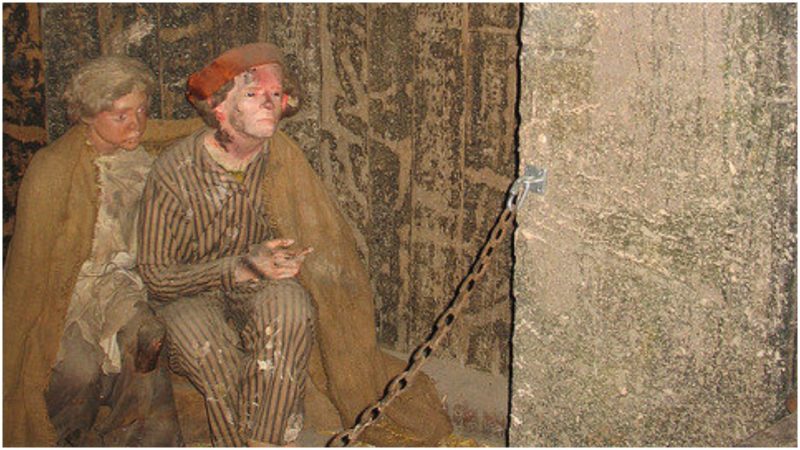

A diverse group of people were locked up within Henry’s prison, with crimes including prostitution, debt, assault, trespassing, following the “wrong” religion, or refusing to attend church services (of the “right” religion).

Because the Liberty was not governed by the laws of the the City of London, certain ventures were allowed within it’s border that could not legally operate in the surrounding area. Thus it was known for gambling houses, bear-baiting, theaters (including Shakespeare’s Globe), and other shady goings-on.

In 1161, King Henry II agreed that the Bishop of Winchester could licence brothels within his Liberty — and, of course, take a fee from them.

Understandably, the Bankside area was rather attractive for a number of small-time crooks, meaning that the gaol was never short of prisoners.

This was good news, to some extent, for the gaolers who supplemented their meager wages by selling perks to the inmates, usually funded by their friends and family on the outside. In addition to candles and palatable food, those who could afford to pay might buy a bed to sleep on instead of the hard floor, a lighter pair of irons, or the right to beg from passers-by.

During the 14th century, the Bishop of Winchester’s domain became known as the Liberty of the Clink. It is uncertain whether the term was first applied to the area, or the prison.

There are a number of theories regarding the origin of the name “The Clink.” One suggests that it derived from the Flemish word for a latch, klink. There were several waves of Flemish immigration to some parts of Britain during this period.

Another theory that suggests that the name has a purely onomatopoeic meaning, deriving from the sound produced by chains hitting against each other, or that of the blacksmiths hammer as it closed the leg and wrist irons on a prisoner.

A third theory suggests that Clink is an old term for the rivets. Whatever its origin, this name became a synonym for a prison, giving birth to the phrase “thrown in the Clink.”

As well as numerous petty criminals, the Clink housed several notable inmates throughout the years. During the Counter-Reformation in the 16th century, under the reign of the Catholic Queen Mary, it was mainly used to confine those accused of heresy.

In the early 1600s a group of Puritans whose followers went on to become the first Pilgrim Fathers to form the Plymouth colony in present-day Massachusetts were held in the Clink.

Following the English Revolution (1642–1651) Winchester House was sold and the Clink became almost exclusively a debtors prison.

It was notorious for harsh treatment of prisoners, which made the Clink and the opulent Winchester House natural targets during civil rebellions against the Statute of Labourers Act — the Peasant’s Revolt in 1381, and Jack Cade’s rebellion in 1450. The prison buildings were rebuilt after both of these riots, but they were in such a state of disrepair by 1745 that inmates were being housed in temporary buildings.

It’s end came in 1780, during the anti-Catholic protests known as the Gordon Riots. The Clink was broken into and all the prisoners were liberated — the prison was set on fire and never erected anew.

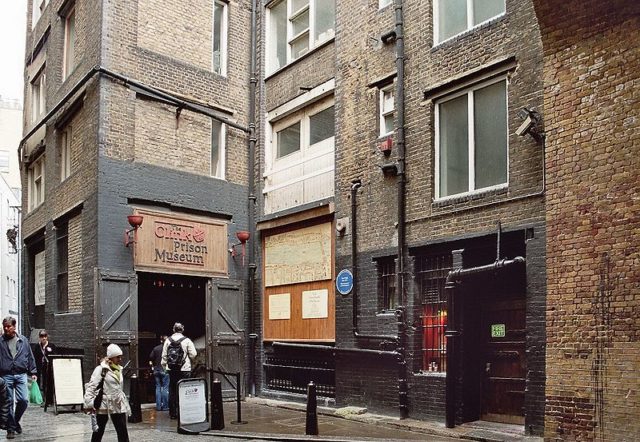

The Clink Prison Museum stands on the same spot as the main men’s prison. Beside it runs Clink Street, where part of the the original gaol wall can be seen.

Other prison buildings would have been scattered around within the museum’s vicinity, their foundations now buried somewhere beneath the streets of London.

The museum offers an unforgettable time to those that come to visit, trying to recreate what the prison might have looked like throughout history.