Nothing but a simple caution sign remains of this old mining town, warning all those who dare to venture close enough of the dangerous radiation levels beyond the barbed wire, and a story about a world-changing event.

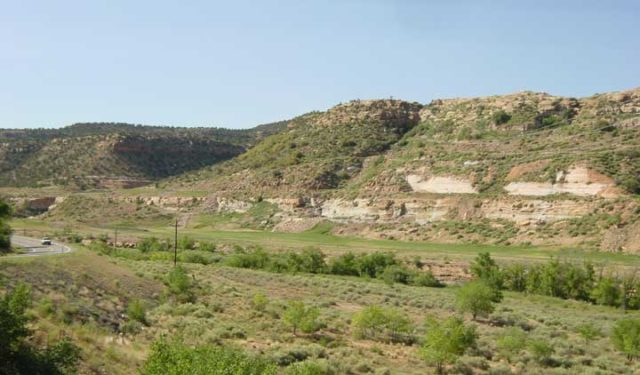

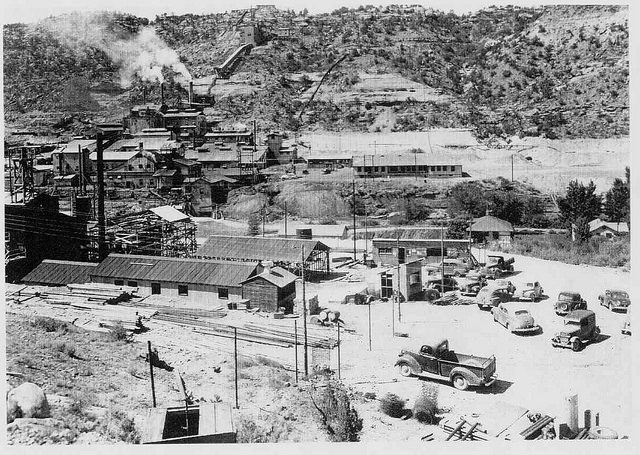

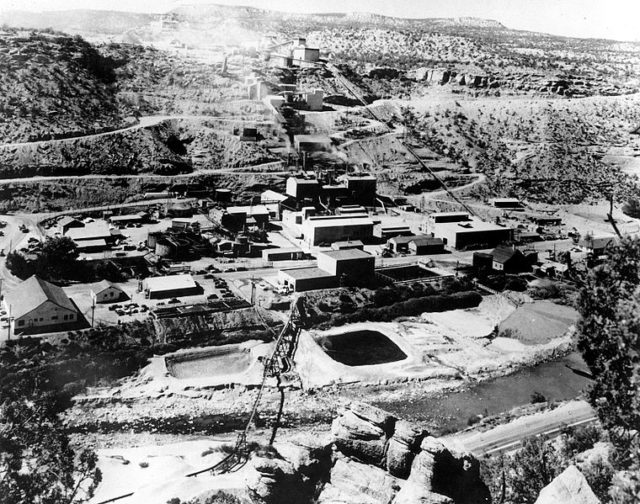

On this remote site in Montrose County, Colorado, was once a company town of U.S. Vanadium, a company that had only one goal — to extract and process the mineral called carnotite, which is rich in vanadium, uranium, and radium. As a chemical element, vanadium is hard and grey and it doesn’t look much, but its uses are copious, from jet engines to superconducting magnets.

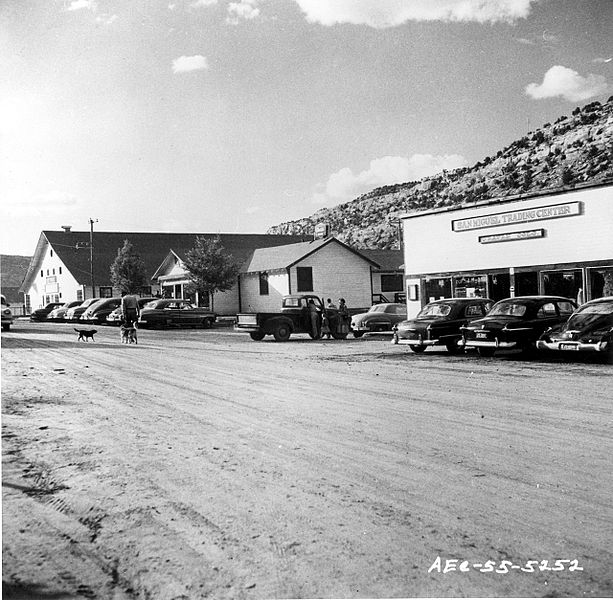

Established in 1936, the town stood roughly 90 miles to the southwest of the city of Grand Junction. At its peak, Uravan numbered around 800 people; the flourishing community had its own school and medical facilities, as well as tennis courts and a recreation center, all provided by the company.

But it was the byproduct that came out of the vanadium processing, the more widely known radioactive chemical element uranium, that gave this town a permanent place in the history books.

Carnotite was discovered in the Uravan mineral belt in 1881 by a gold prospector named Tom Talbert. When he first stumbled upon this arcane and enigmatic yellow substance, it was a quite unremarkable find.

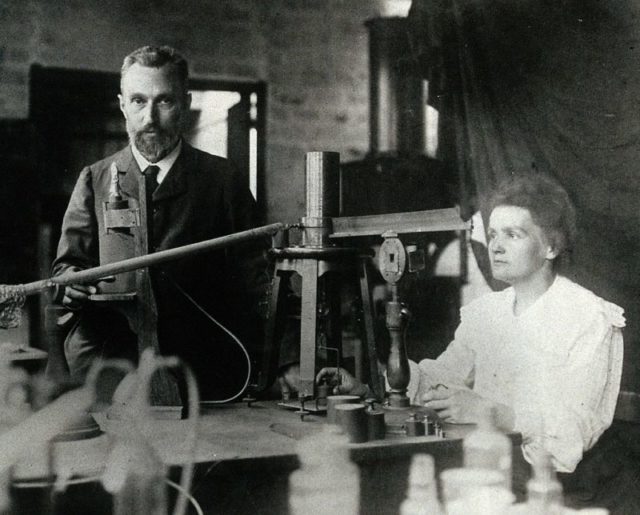

Almost two decades later, Marie Curie’s discovery of radium and polonium and her research into it’s use for medical purposes gave value to Talbert’s carnotite. As she and her husband Pierre laid the foundations for the development of radiotherapy and nuclear medicine, other researchers started looking at other uses for these new radioactive substances.

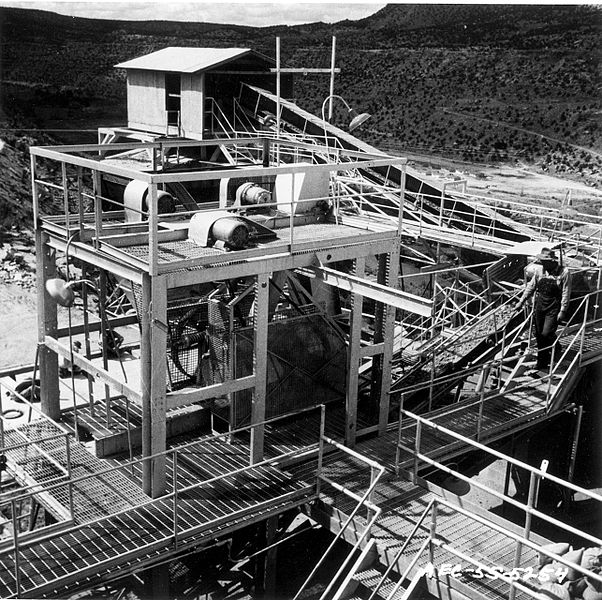

It was then that the market for carnotite was born and individuals and companies alike all wanted to be part of it. Mining for carnotite started at Uravan on a small scale in 1914, then in 1915 the Standard Chemical Company erected a uranium processing plant named the Joe Jr. Mill. Before the dangers of radioactive substances were understood, uranium was widely used in luminous paints, for example on watch dials and gun sights.

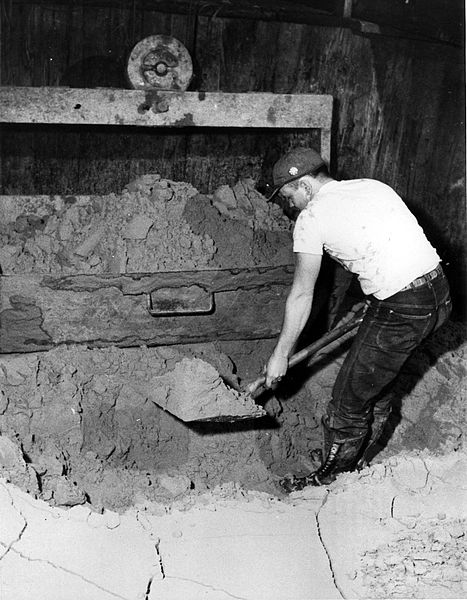

The company was successful throughout the First World War but eventually lost in battle with the competition. It was 1928 when the U.S. Vanadium bought Joe Jr. Mill and slowly began to craft a community. The vanadium plant at Uravan processed carnotite from several nearby mines, and a secondary mill was built in the 1940s to process the byproduct into radium oxide, also known as “yellowcake.”

Around this time, the United States government began work on an ultra-secret project that years later would become known as the Manhattan Project. In its essence, this program was designing the first weapon of mass destruction, and in the heart of it all, there stood uranium.

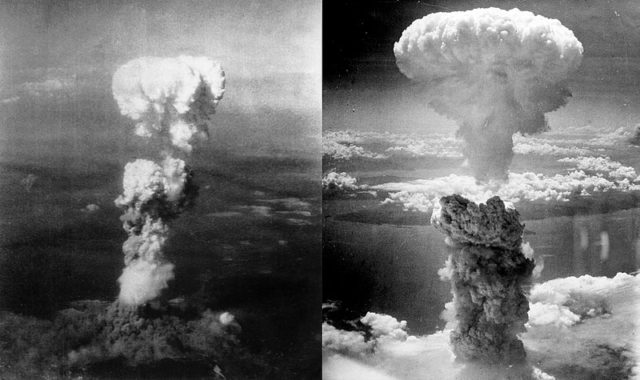

It was in 1945, at a cost of $35 billion, inflation adjusted for 2018, that the R&D team of the Manhattan Project gave birth to a nuclear weapon. The yellowcake from Uravan was enriched and used to build the first and only nuclear weapons to be deployed in war; those detonated over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The end result was 130,000 dead and many others facing long-term health defects.

The government acquisition of uranium for the country’s defense program continued to keep the Uravan Mill lucrative into the early 1970s. After this funding dried up, and public fear of radioactive substances increased, especially following the 1979 Three Mile Island accident, the once-thriving town of Uravan fell slowly into decline.

By 1986, it all was over: Uravan was declared a Supersite and became a ghost town. Two years later, the whole town was torn apart and buried in order to prevent an environmental hazard. Nothing but a yellow sign remains today on the spot where an innocuous looking yellow substance once provided a livelihood to thousands of men and women, but sadly also killed hundreds of thousands more.