Baltimore is a large city located in Maryland, near where the Patapsco River empties into the Chesapeake Bay. Once a thriving center for industry, the city fell into decline following the Second World War, something from which it has yet to recover. This is due to a number of reasons, most notably the city’s crime rate, economic issues and its history of racial segregation.

Today, Baltimore is considered a prime example of urban decay in the United States.

A city steeped in architectural history

Baltimore was once the sixth-largest city in the US, with around one million residents living there in 1950. It’s divided into nine geographic neighborhoods, the majority of which are considered residential areas or a mix of residential and industry. The major commercial district is located in Central Baltimore, while West Baltimore is the city’s largest Black residential community.

Baltimore is home to a number of historic architectural styles. Its streets are organized into a grid pattern of tens of thousands of brick and formstone-faced rowhouses. Nicknamed the “city of neighborhoods,” the urban center is home to 72 designated historic districts.

Among the city’s most notable architectural sites are the Phoenix Shot Tower, which until the American Civil War was the tallest building in the country, and the neoclassical Baltimore Basilica, which is among the oldest Catholic cathedrals in the US. There’s also the Greek Revival-style Lloyd Street Synagogue.

Racist attitudes have heavily impacted Baltimore over the years

Like many major cities that once had economies highly dependent on industry, Baltimore has a large African-American population. In 1910, a city council ordinance required that each residential block be segregated, something that was reinforced during the Great Depression when US President Franklin D. Roosevelt bailed out homeowners who were at risk of losing their residences – something that didn’t apply to Baltimore.

The city was deemed “unsafe” for development by the federal government, which resulted in mortgage lenders refusing to issue loans there. This further exacerbated Baltimore’s racial segregation and urban decay in the city’s Black neighborhoods. This had a ripple effect that’s disproportionately led to poverty and high crime rates for that portion of the population.

Economic decline leads to increased poverty

Following the Second World War, the industry that largely made up Baltimore’s economy began to decline. This was initially seen through the decrease in demand for shipping and was closely followed by the closure of the city’s steel factories, which led to the loss of high-paying jobs. While these gaps in the employment market were replaced by service positions, they didn’t pay near what those lost did.

As a result of the loss of industry, Baltimore’s economic and social decline has been compared to that of towns in the midwest’s Rust Belt. According to a study released by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics in March 2018, the city’s unemployment rate was at 5.8 percent, with one-quarter of the population living in poverty. Those able to leave and find new jobs, did, and as of the 2020 census, Baltimore’s population had decreased to 585,708.

Outside of the lack of high-paying jobs, Baltimore’s decline can be attributed to the city’s high taxes, which have kept businesses and middle class families away, and its still-highly segregated population. The latter has meant that initiatives geared toward improving the city have largely benefited the White population, as opposed to minorities.

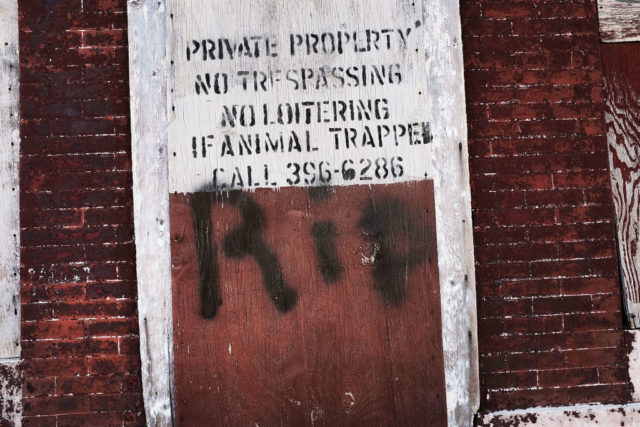

High poverty and the decrease in population has resulted in a number of houses and factories around Baltimore being boarded up and abandoned. The city’s homeless rate has continued to increase, and its overall state once led Senator Bernie Sanders to compare Baltimore to the “third world.”

Baltimore’s crime rate is incredibly high

Violence has been a part of Baltimore’s history for decades, with a notable increase occurring during the crack epidemic. The city’s crime rate peaked between 1993-96, with 96,243 incidents reported in 1995. This was a mix of gang-related activities and murder, among other crimes. The homicide rate was – and remains – particularly high, especially in high-poverty neighborhoods.

Outside of gang activity and murder, Baltimore is also experiencing a high rate of drug-related deaths. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), around 10 percent of the city’s population is addicted to heroin. As well, Baltimore is ranked second in annual opiate deaths for cities with a population of over 400,000.

To try and lessen the amount of crime in the city, city councilor Martin O’Malley launched a 1999 campaign for mayor on the basis of a zero-tolerance model. While this saw a decrease in violent incidents, it also led to an uptick in arrests, which had a ripple effect. The majority of those arrested were young Black men, who were not only given a criminal record, but also unable to make a living for themselves while imprisoned.

Following the police-involved death of Freddie Gray in April 2015, the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division released a report, accusing Baltimore’s Police Department of racial discrimination and excessive force – something the Black community had been complaining about for years. Following the report, the city agreed to a “consent decree,” which would see police reforms enforced by a federal judge.

Baltimore is slowly being revived

Over the decades, there have been numerous efforts to revitalize the city. In 1975, a group of advertisers nicknamed Baltimore the “Charm City,” and a number of landmarks were constructed in the years after. These included the Maryland Science Center, the Harborplace, the Baltimore World Trade Center and Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

In recent years, notable structures built in a similar vein include the John Hopkins Hospital, which is among the largest medical complexes in the US, and the reopening of the Hippodrome Theatre.

The efforts in the late 20th century also spanned into the HIV/AIDs epidemic, during which Baltimore City Health Department official Robert Mehl convinced the mayor to form a committee to address the growing food crisis. This led to the creation of the Moveable Feast charity in 1990.

In September 2016, Baltimore city council approved a $660 million bond deal to help in the construction of the $5.5 billion Port Covington redevelopment project. Goldman Sachs also invested $233 million. The project, which is still under construction, will see the waterfront development of housings, manufacturing spaces, shops and offices, and is slated to be the new home for the Under Armour headquarters.

It’s projected that the initiative will create 26,500 permanent jobs and bring in $4.3 billion annually.

More from us: Detroit’s Decline: How the Automobile Capital of America Fell Into Poverty

There are also a number of also strategies being put in place to help revitalize Baltimore. These include investing in Middle Market neighborhoods and areas along major transit routes; building upon existing amenities and assets; investing in anchor institutions, redevelopment, and the city’s art and entertainment industries; and the facilitating of investment in emerging markets.