Cleveland, Ohio once saw unprecedented growth that led it to become the sixth-largest city in the U.S., but recently residents have fled from the area as major employers have closed their doors. While other major cities’ populations grow each year, Cleveland is the fifth-fastest shrinking city in the U.S. with its population falling 0.5 percent each year since 2014. Cleveland’s population peaked in the 1950s at 914,000 residents, and has now fallen to 372,624 – prompting some to call it a “dying city.”

What remains of the once-prosperous city is a derelict, run-down example of what happens when local industry fails.

History of Cleveland

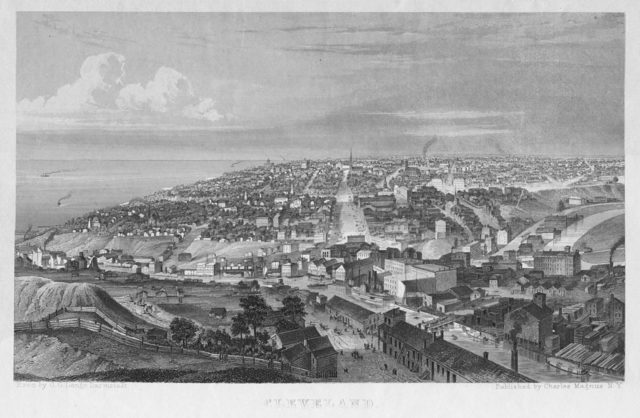

Cleveland was first established in 1796 by General Moses Cleaveland. Located on the shores of Lake Erie, the settlement offered improved access to the necessary waterways of the Great Lakes which were especially helpful during the War of 1812. When the Ohio and Erie Canal was completed in 1832, a whole new world of possibilities opened up. The canal system not only connected the Ohio River to the Great Lakes, but it also extended to the Atlantic Ocean via the Erie Canal and Hudson River, and later on through the Saint Lawrence Seaway. This meant products could be shipped to markets in the South and along the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River.

The area was also a prominent location for abolitionists during the Underground Railroad as one of the last stops before escaped slaves made it to freedom in Canada. After the Civil War, Cleveland became a hub of industry and success, especially in the manufacturing sector. Between 1810 and 1850, Cleveland’s population grew from under 1,000 people to more than 40,000 – likely thanks to the increasing number of jobs in the transportation and manufacturing sector. In 1870, the city grew rapidly again when John D. Rockefeller founded Standard Oil in Cleveland, providing thousands of jobs to locals and a growing population of immigrants from all around Europe.

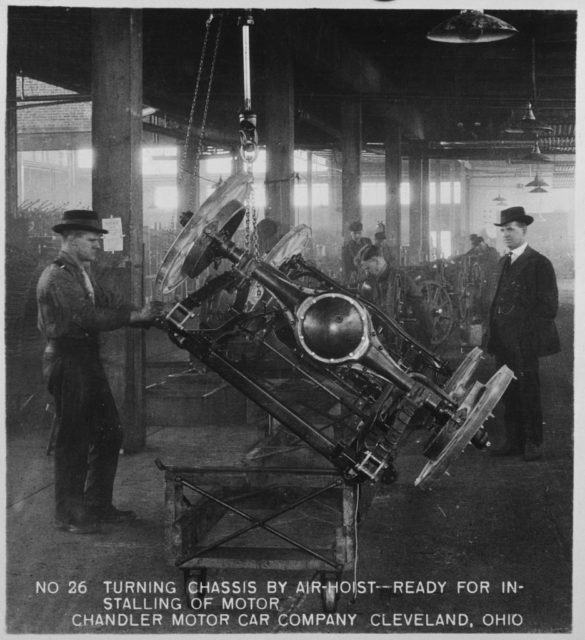

In the early 20th century, Cleveland was home to several successful automotive companies including Peerless, Jordan, Chandler, and Winton – makers of the first automobile driven across the United States. Steel was also a vital part of Cleveland’s economy, as a substantial percentage of local workers were employed at steel mills. This period of prosperity created a thriving love of arts and culture in the Cleveland community, including the City Beautiful movement of architecture that introduced the beautification of buildings and open spaces that harkened back to “simpler times.” Around this same time, the famous Cleveland Museum of Art and the Cleveland Orchestra were founded.

The ’20s and ’30s in Cleveland were just as lavish as in New York or Los Angeles. Prohibition was poorly enforced and flappers could be seen prancing around Downtown Cleveland shopping in major department stores like Higbee’s, Halle’s, the May Company, and Sterling Lindner Davis – a collective of some of the most fashionable stores in the country that was often compared to New York City’s Fifth Avenue.

Following the end of World War II, Cleveland reached its highest population, but would also start its slow descent into a ghost town. In the span of just 50 years, Cleveland’s population dropped by half. Changes to the steel and railroad industries resulted in countless layoffs, and the 1969 fire on the Cuyahoga River caused by an oil slick drew national attention to Cleveland’s over-polluted waterways. Things escalated even further during the recession in the early 1980s which caused Cleveland’s unemployment rate to rise 13.8 percent higher than the national average thanks to the closure of several steel production plants.

Cleveland clean-up

In an attempt to change the rapidly declining future of Cleveland, city leaders worked tirelessly to transform the arts sector into a thriving cultural center of the midwest through attractions like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Cleveland Orchestra.

Cleveland has also become a shining example of environmental progress thanks to its successful cleanup of the Cuyahoga River. The river spent years absorbing the waste from Cleveland’s industrial businesses, and by 1969 it was so polluted a shower of sparks nearby caused the water to ignite. The Cuyahoga River fire finally brought the needed attention to the environmental impact of Cleveland’s industrial practices, and resounding public outcry over the fire eventually led Congress to pass the Clean Air Act in 1970 and the Clean Water Act in 1972.

Families forced to leave

The river wasn’t the only thing in need of a cleanup. As the local economy plummeted and those who could afford it moved to the suburbs, entire neighborhoods were left in shambles. The lack of employment opportunities has forced many families to leave the Cleveland area, and those who stay behind often face significant financial stress which can impact other aspects of their lives. In fact, a 2022 study conducted by WalletHub has named Cleveland as the “most stressed city in the country” for the third year in a row.

A professor at Cleveland’s Case Western Reserve University explained how inflation is contributing to the already dire economic situation: “You’re working and you’re trying to toil along, but your paycheck is just not going quite as far as it used to,” John Ernest said. Money can also put a strain on personal relationships and mental health, which further contributes to Cleveland’s “most stressed” status.

More from us: Racial Segregation and Poverty: The Story Behind Baltimore’s Decline

Today, another recession looms over Cleveland after the COVID-19 pandemic – and according to some, many more will be forced to flee the city when it arrives.