Bearing the title of “Montana’s Silver Queen,” the history of this town involves thousands of people and lots of silver. Situated up the Granite Mountain and to the south of Philipsburg, Granite was once home to some 3,000 residents.

It all began in 1875 with a man by the name of Eli Holland, who first discovered silver in the area. For the purpose of extracting the silver, Eli dug a small pit where he did some initial excavations and found small deposits of “ruby silver,” though he later abandoned the site.

Five years later, Charles D. McLure, the manager of Hope Mill in Philipsburg, discovered silver ore. It wasn’t long before a partnership was formed between McLure and Charles Clark, and thus the Granite Mountain Mining Company was born.

With the help of investors from St. Louis, Missouri, these two men managed to secure capital of $10 million. Over the next two years, $130,000 was spent on fully developing the mine. Then in 1882, luck was once more on their side when they discovered a huge silver vein. Given the fact that this lode yielded 1,700 ounces of silver per ton, the pit was nicknamed the Bonanza Chute.

This vein returned a profit of close to $300,000 in just one year – or around seven and a half million dollars with inflation adjusted for 2018. Such huge profits attracted other prospectors in the area and over time a town was born. The newly arrived folks settled around this prosperous mine.

Lots for prospecting were rented to the newcomers for $2.50 per month. As the town grew, neighborhoods were developed, including districts such as Finnlander Lane and Donegal Lane. This is where the miners of Danish and Irish origin were settled.

The mine’s managers and superintendents lived in the area known as Magnolia Avenue. This is also where the doctors lived, as well as a number of other professional people. According to Legends of America, this neighborhood “soon took on the nickname of Silk Stocking Row.” The popularity of this town grew so much with time that even miners from China came to be part of it. Among other districts, the town of Granite also had a Red Light District.

Despite its popularity, Granite had no running water. Wagons were used to haul water from the Fred Burr Lake for many years, until a cistern system was installed.

In 1889, Granite Town had four churches. There was also a newspaper that circulated named the Granite Mountain Star. For the needs of the younger members of the population, there was a school. A total of 18 saloons were opened to entertain thousands of residents. Among other businesses, there was a bathhouse, as well as a hospital, a bank, and a hotel that rose three stories above street level.

But not all was hard work and toil. Entertainment and recreation was also an integral part of Granite’s story. There was a roller-skating park, and during the winter months there was the bobsled run. The end of this town came as a result of the 1893 repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which dealt a devastating blow to Granite and to other mining towns when it cut the prices of silver in half.

In just one year, thousands of people left the town and the population dropped to barely 150. Granite was on the verge of becoming a ghost town. The last resident of Granite, Mae Werning, died in 1969.

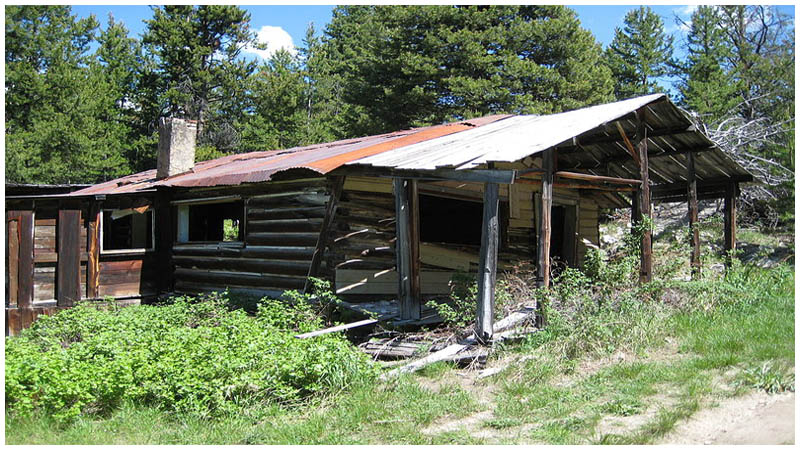

Today this town is part of Montana State Park. Much of the town’s buildings have deteriorated beyond repair, but nevertheless, people still come to visit this town that was both created and destroyed by silver.