The Saint Kilda archipelago is the most western group of islands belonging to the Scottish Outer Hebrides, all the way out in the Atlantic Ocean around 41 miles (64 km) to the west of its nearest island neighbor, Benbecula, and 112 miles from the mainland of Scotland. This archipelago consists of four islands, of which Hirta Island is the largest, although it is actually not very big. It has just 9.3 miles (15 km) of coastline and a total area of less than 2.5 square miles.

The island chain was created long ago by a volcanic eruption, and Hirta Island is what is left of the old volcano. Its topography is dramatic, with high slopes plunging steeply down to the ocean waves. Due to the rugged terrain, the island can only be accessed at one point, where a small bay has naturally formed over the years. It can take up to 18 hours to reach Hirta by boat from the mainland, and from the Isle of Skye around 3 to 4 hours, a journey that is dependent on weather and tides. It is not unheard of for the boat to have to turn back if the sea gets too rough, even during the summer. The turbulent sea makes St. Kilda inaccessible for much of the year.

But amazingly, people have lived on this tiny isolated piece of land from prehistoric times until the last permanent residents left in 1930. There is archaeological evidence of a Viking settlement and the remains of Viking burial tombs. In the 15th century, St. Kilda was part of the Kingdom of His Excellency of the Islands until he passed the ownership to MacLeod of Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye. As part of the payment of rent from the Hirta islanders, MacLeod accepted feathers collected from the seabirds which the islanders caught for food by climbing up the sheer cliffs.

There are the remains of three different old chapels on the archipelago. They were dedicated to San Brendano, Santa Columba and one to the Body of Christ. One more interesting ruin suggests that a great common house existed on Hirta that archaeologists call the “Amazon’s House.”

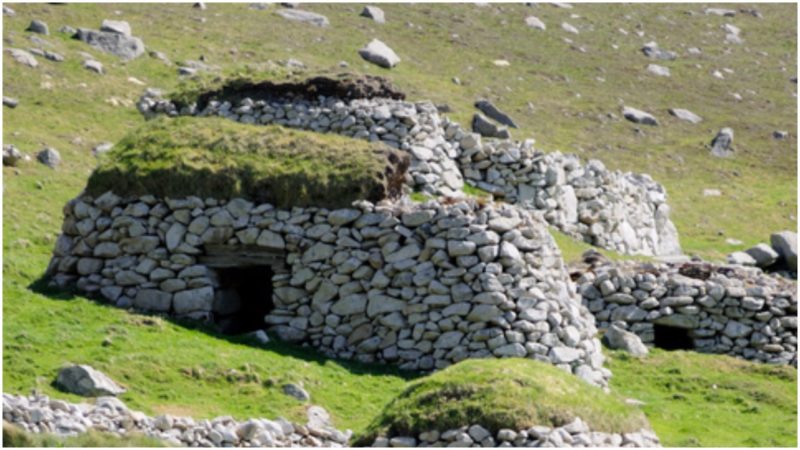

Living on the Island of Hirta must have been very hard. Only truly resilient people could make survive there. Those who did exploited the limited resources the island had to offer, mostly relying on the colonies of birds for meat, eggs, and oil. Alongside the stone houses, people built small shelters called cleits in which meat was dried and stored. Fishing was possible when the weather allowed, and they were able to grow hardy crops such as potatoes. At some point, a breed of highland sheep was introduced to Hirta which supplied milk and wool. The village was communally governed by a council consisting of all the men on the island.

After centuries of having little contact with the outside world, during the mid-19th century, tourists began to visit the island. Over several decades, as tourism to the St. Kilda islands grew, the residents of Hirta slowly came to rely on the income that could be made from the visitors as well as the supplies brought by boats that came during the short summer period when tourists visited.

During the 1800s, the Scottish Highland and Island Emigration Society was set up. This was a charity to help people left destitute by the Scottish potato famine begin a new life in Australia. At the time, the Australian government had a state-funded immigration scheme to encourage people to make the long journey and settle there. 42 islanders left Hirta in 1850 on an ocean voyage which would have taken several weeks–about half of these pioneers survived.

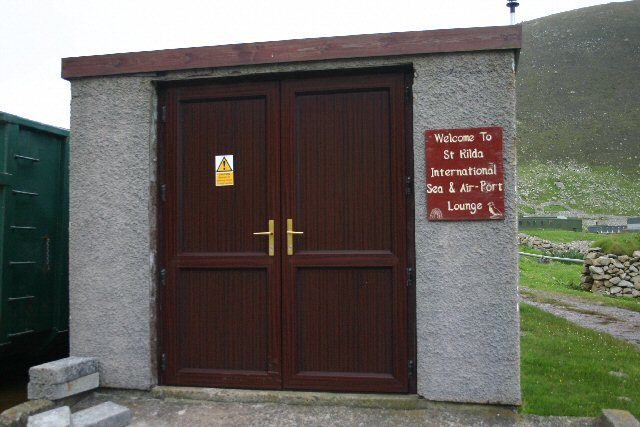

A series of events over the following years finally led the remaining residents to petition the Scottish Government to help them abandon Hirta and resettle on the mainland. The increased contact with non-islanders brought more diseases, notably an outbreak of influenza in 1914. It is also thought this was the reason for the sharp rise in infant mortality. During the First World War, the British Navy set up a base on the island, and this continued to be used after the war as a missile tracking station, linked to the missile base at Benbecula. The islanders could now benefit from regular mail and supplies via the Ministry of Defence (MoD), but the downside was that they became more aware of how other people lived, and even more despondent about the daily challenges they faced for survival.

The last 36 residents of Hirta Island were evacuated in the summer of 1930 on HMS Harebell to live and work in the Fiunary Forest, which is managed by the Forestry Commission. Ironically, this was the first time most islanders had ever seen a tree. Since then, the island has had no permanent residents, but there are always a handful of temporary ones. Since the MacLeod family gave Hirta to the Scottish National Trust in 1957, trust volunteers, and at times various scientists, spend the summer on Hirta. The MoD base, which is planned to be redeveloped to be more in keeping with the natural environment, is manned year-round. In the summer, it is also possible to charter a boat from Skye to visit the island.

The position of the island and its unique climate make it an ideal breeding ground for thousands of seabirds. More than 100,000 seabirds, including puffins and gannets, live and rear young on this island.