Ironton , Colorado was built almost as quickly as it disappeared. The town was founded on the back of the silver mining industry, and survived years of decline, but ultimately would not last. Now, few remnants remain of this once-thriving ghost town.

The beginnings of Ironton

Pushing their way up Mineral Creek and north of the town of Silverton, a couple of prospectors managed to discover rich deposits of gold, silver, and copper. The year was 1879, and the whole area very quickly came to be referred to as the “Red Mountain Mining District.”

In 1881, a prospector by the name of John Robinson decided to explore a bit more around the area. According to oral tradition and what information has managed to survive throughout the years, Robinson’s continued hunt caused him to discover an abundance of high-quality lead and silver in the area as well. Soon, two new mines were born dubbed “The Yankee Girl” and “The Guston Mines.”

The region was known as Ironton Park, and with the found riches, it didn’t take long before others decided to join Robinson in pursuit of fortune. One by one, and each with their own dream of a better tomorrow, they began to settle down.

The park becomes a town

Two years after the initial discovery, a small town called Copper Glen was born. By April that same year, the town received the moniker “Ironton,” and by spring 1884, Ironton town was officially incorporated. While the number of residents grew relatively slowly, new people did arrive each month. A large percentage of people were living in tents, although over time the town developed all of the commodities of modern life. There were no less than twelve saloons and four restaurants in Ironton at one point; there was even a bookstore.

In 1889, the Silverton Railroad came to the nearby town of Silverton. This narrow-gauge short line connected the Red Mountain Pass, where Ironton was located, with Silverton. By 1890, Ironton was home to around 320 people – enough to keep the mines operating smoothly and to keep the wagon traffic constant or around two trains per day fully packed with silver ore.

Things got a little shaky

However, these days of abundance did not last. In 1893, the U.S. Government decided to demonetize silver – an action that caused a crash in silver prices. But this wasn’t the only problem Ironton’s miners were faced with. The whole area was also rich in sulfide ore, which was also mined. When it came into contact with the underground waters, this ore turned into sulfuric acid, a chemical that constantly damaged the miners’ equipment. With the market for silver at its lowest and the additional costs of maintaining equipment, production at Ironton dropped.

To top things off, the Silverton Railroad decided to pull back from the area and to relocate its services to Red Mountain Town. This may sound like the final demise of Ironton, but it simply served as the end of the silver era in the area. Ironton continued to survive, as in 1898, gold was discovered.

Six years later, a project was launched to drain the mines, hoping to reinvigorate the town. The whole operation lasted for three years but was all in vain. Despite all efforts, Ironton’s population and popularity continued to drop. During the 1910 census, the town had less than fifty people.

The final end of Ironton

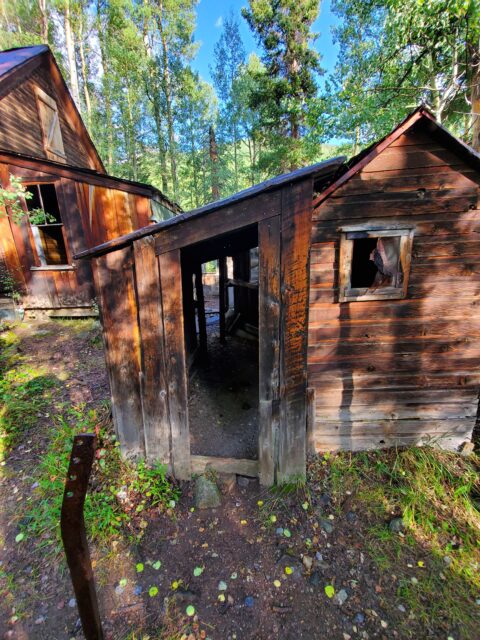

A decade later, the post office shut its doors. Almost everyone left soon after, and as if that wasn’t enough, a number of wildfires made sure to erase almost every trace of this small and once prosperous town. As the years went on, the number of small buildings that managed to survive the fires fell victim to heavy snowfalls and fell under the pressure.

Read more: Huber Breaker: A Landmark of America’s Coal Mining Past That’s Since Been Demolished

According to researchers, the last people to leave the town were two miners named Harry and Milton Larson. Harry passed away in the 1940s. Milton lived for two more decades and passed away during the 1960s. Only a handful of buildings remain standing today to serve as reminders that there was once a prosperous town up in these mountains.