To this day, Leadfield is probably the biggest scam in the mining world: a brutal deception and deceit brought unto prospectors full of hope and dreams. This piece of history became very popular with writers and journalists, who popularized it further, burning it deep into the mining lore of California.

What is today a ghost town lived through a great boom between 1925 and 1926. This was the result of a great promotional campaign lead by a unique character named C.C. Julian. He was responsible for both the rapid expansion and equally successful demise and abandonment of Leadfield. Probably the best way to describe his persona is with the words of the western historian Betty J. Tucker, who in the 1971 issue of Desert Magazine wrote the following:

“This town was the brainchild of C. C. Julian, who could have sold ice to an Eskimo. He wandered into Titus Canyon with money on his mind. He blasted some tunnels and liberally salted them with lead ore he had brought from Tonopah. Then he sat down and drew up some enticing, maps of the area. He moved the usually dry and never deep Amargosa River miles from its normal bed.

He drew pictures of ships steaming up the river hauling out the bountiful ore from his mines. Then he distributed handbills and lured Eastern promoters into investing money. Miners flocked in at the scent of a big strike and dug their hopeful holes. They built a few shacks. Julian was such a promoter he even conned the U. S. Government into building a post office here.”

Now, it is not completely false that the Leadfield mining area had no ore. In fact, it did, it was even quite rich with it. But about twenty years before C.C. Julian advertised it as such. In the early 19th century, Leadfield was part of the examination and excavation as well as the whole area of Titus Canyon. And was proven prosperous for some lucky prospectors. The individual prospectors, soon after discovering the rich ore, sold their claims to a bigger ore company and got somewhat rich without even getting their hands dirty.

The company that bought and developed the area was named Death Valley Consolidates. They invested a good amount to start digging and shipping ore to the smelters. However, they soon discovered that their ends did not meet. Smelters were too far and shipping the ore to them proved to be a hard and expensive task. After two years of mining, they decided to close off the mine shafts and carry on with operations elsewhere.

Leadfield mining town reached its peak and boom in 1926 with just over 300 people living and working there. At this time, a road was built up the canyon, fifteen miles long, in order to connect the town with the main road to Beatty, Nevada.

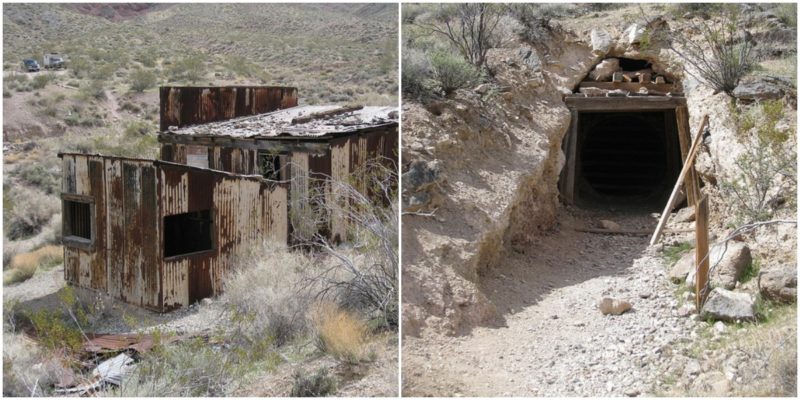

Along the road, wooden poles were nailed to the ground with concrete to support electric lines going all the way up to the canyon and the town. Some old photographs show very little corrugated buildings and a few dugouts, old school underground houses. However, most of the population of Leadfield lived in tents made out of different materials and of different sizes.

Just after its peak, only the following year Leadfield died. The post office was shut down. Citizens soon woke up from the illusions and realized there was nothing to be found there. And everyone in a matter of months drifted away to another place where they would get rich. The remains of the Leadfield mining town are sparse: a couple of scavenged metal sheds, two locked mine shafts entries, and many indications of what used to be both a livable and industrial area. Since 2005, the town can be reached following the one-way Titus-Canyon Road starting from the eastern end of Titus Canyon, Nevada.