Lynch, Kentucky is still an inhabited community. However, it’s nothing like the city it once was. Founded during the coal mining boom of the early 1900s, Lynch has declined to near non-existence. The residents who remain are struggling to keep their home alive, and the buildings that remain standing make the city look as though it was abandoned long ago.

Lynch was built by the US Steel Company

Lynch was founded by the US Steel Company in 1917, due to the high demand for steel brought about by the First World War. The company purchased over 19,000 acres near Looney Creek, located at the foot of Black Mountain, for the camp to be built upon. Its remote location meant supplies needed to be shipped by train to a nearby city, after which they were brought to the area by mule and carriage.

Construction carried on past the war’s close, and it was officially completed in 1925. The settlement was named “Lynch” after the Father of Mine Safety, Thomas Lynch, who also served as the first president of US Coal and Coke, a subsidiary of the US Steel Company. Unlike other mining towns, it was home to beautiful buildings, paved streets and an advanced sewage system that made life enjoyable for residents.

Work began straight away, with the first coal shipment leaving the city in November 1917. The first official passenger train to the area ran in 1920, as Lynch rose in popularity. At its height, the area had a population of around 10,000 residents, the majority of whom were immigrants who’d arrived in the United States via Ellis Island. Residents were recorded to have come from at least 38 different countries, making Lynch one of the most diverse cities in the area.

Setting world records

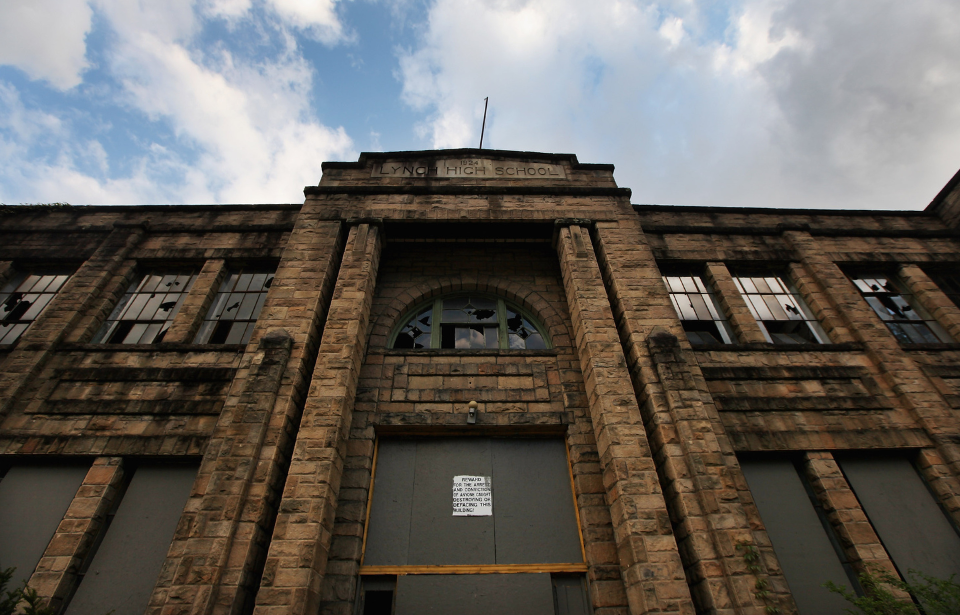

By the 1940s, Lynch had become the world’s largest company-owned coal town. It featured over 1,000 buildings, made with beautiful local stone. These included a theater, hotel, hospital, commissary, churches and a school. There was also a post office and funeral home.

The US Steel Company had control over the city’s functioning, which meant it operated with no mayor, electoral council or police force. The business was responsible for maintaining the buildings, caring for the sick and policing residents.

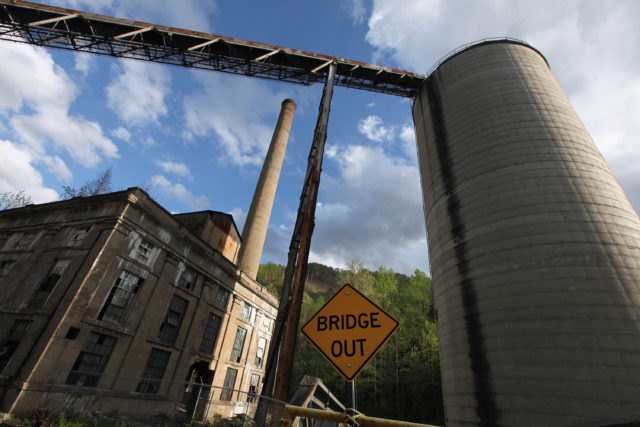

Lynch was located in an area rich in coal. As the city became more established, so, too, did mining practices. The operation became more efficient, and, in 1923, Lynch set a world record for the most coal produced during a nine-hour shift: 12,820 tons. This was possible due to the plethora of coal in the area, as well as the mines being the first fully-electrified ones in America.

As coal production declined, the US Steel Company withdrew

Unfortunately, Lynch’s success wasn’t to last. As demand for coal diminished following the Second World War, so, too, did the city. Younger residents moved away, and people were no longer lining up to take their place. Most took favor with bigger cities. By the 1960s, the population had dwindled so much that the US Steel Company began to take down many of the public buildings it had erected.

The US Steel Company didn’t demolish the entire city. Whatever was left standing was sold to the residents. Thus, Lynch became incorporated in 1963. This allowed residents to introduce an electoral system, with their own mayor and city council.

In the matter years, Lynch went from being one of the world’s largest and most successful coal mining camps to the shell of a city struggling to survive.

Lynch still exists, but barely

Today, most of the coal mines in Lynch have been abandoned. Just under 700 residents still live there, so the city still has a pulse, of sorts. However, it’s struggling financially, operating month-to-month. There are no new jobs, and the city is finding it difficult to pay the small number of employees that work there.

More from us: The Gulag-Style Incarceration of Political Prisoners at Spaç Prison

That being said, what is left of Lynch has been well-preserved. At over 100 years old, the city barely exists, yet the residents who remain are asking for help to keep it alive. “This town was built to last,” said life-long Lynch native Reverend Ronnie Hampton. “It’s still here. There have to be industries, something, that can hold this town together… The town in just kind of going to waste.”