In a study published to the journal Antiquity, archaeologists have shared their belief that the lost city of Natounia has finally been located. The city, constructed during the first century BC as part of the Parthian Empire, has been compared to Helm’s Deep in J.R.R. Tolkien‘s The Lord of the Rings, and its discovery is big news. Aside from a handful of ancient coins, there are no known historical records to denote Natounia’s existence.

History of the Parthian Empire

Natounia, also known as Natounissarokerta, is located in the mountains of Iraq‘s Kurdistan Region. It was part of the Parthian Empire, which existed between 247 BC and 224 AD. Primarily situated in modern-day Iran and the lost region of Mesopotamia, the Parthians were considered a major political and cultural power in the region.

According to historians, the Parthians were enemies of the Roman Empire, resulting in the two civilizations fighting in numerous battles over the course of 250 years. During its existence, the Parthian Empire is said to have played an integral role in the formation of Eurasian globalization through its relationships with not only ancient Rome, but Han China and India, as well.

Have archaeologists located the lost city of Natounia?

It’s believed the ruler of the city was the founder of the Adiabene Dynasty, Natounissar. While not well-known, he is believed to have led the dynasty when the Parthian Empire was at its most powerful, with his base being the Rabana-Merquly fortress. He also likely played a role in the establishment of Hatra, an ancient desert trading city in Upper Mesopotamia.

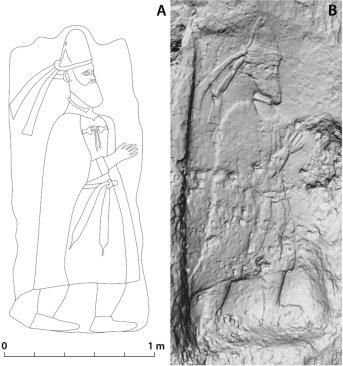

He was tentatively identified as Natounia’s ruler based on similarities between the reliefs at Rabana-Merquly and a statue of an Adiabene king in Hatra. Both feature full beards, fin-shaped headwear, belts with hanging tapered ends, raised right arms with their palms open, neck rings and sleeveless cloaks. The primary difference between the reliefs is that the one in Hatra features a sword resting on the statue’s left hip.

Other key evidence is the aforementioned ancient coins, which feature the name “Natounissarokerta,” as well as the location “on the Kapros” – the modern-day Little Zab River. They’re believed to date back to the 1st century BC.

Speaking with Artnet, Michael Brown, the study’s lead author and a researcher with the Institute of Prehistory, Protohistory and Near-Eastern Archaeology at Heidelberg University in Germany, said, “There are [not] any detailed historical references. Rabana-Merquly is … the largest and most impressive site of the Parthian era in the region, and the only one with royal iconography, so it’s by far the best candidate.”

Architectural features of the Rabana-Merquly fortress

The actual structure of Rabana-Merquly stretched 2.5 miles along the eastern border of Adiabene, with two smaller settlements situated in the area. The structure’s fortifications show that thought and planning went into its design and construction, and it was likely used for trading with pastoral tribes and conducting government business.

A religious complex was also found that could possibly have been dedicated to the Zoroastrian Iranian goddess, Anahita.

Some of the surviving structures suggest the fortress served a military purpose, with the remains of several rectangular buildings having been uncovered, which resemble barracks. This was likely also aided by the area’s natural defenses, such as the mountains upon which it was built. In fact, it’s these features that have allowed researchers to compare Rabana-Merquly to a specific mythical location.

“If you’re familiar with Lord of the Rings, it’s basically a real-life Helm’s Deep,” said Brown, referring to the fortifications in The Two Towers.

Work will continue in the area

Current work at the site is being funded by the German Research Foundation, as part of its priority programme 2176, “The Iranian Highlands: Resilience and Integration of Premodern Societies.” According to a press release, the aim of the project is to “investigate Parthian settlements and society in the Zagros highlands on both sides of the Iran-Iraq border.”

The first major excavation attempts began in 2009, with the latest occurring between 2019-22. The work done in 2009 uncovered parts of Natounia, but the terrain and dense tree coverage made it difficult to gain a full view of the complex. As such, it was initially believed to be a single, isolated building, with smaller ones situated nearby.

“The latest work is significant because we now understand that all the various archaeological features in the area – castle, rock reliefs, sanctuary – are parts of a single massive fortified settlement,” Brown told the National. “Before, some parts were known, but we didn’t understand the relationship. The settlement is strategically located on the edge of the mountains, so undoubtedly played a role in controlling the surrounding restive highlands.”

More from us: From Riches to Ruins: New York’s Haunted Bannerman Castle

Michael Brown collaborated on the research with colleagues from the Directorate of Antiquities in Sulaymaniyah, in the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan.