In the far northeast corner of Oklahoma sits the town of Picher, a once-thriving mining town. At its peak, it was a beacon of opportunity, drawing thousands of workers and their families. However, today, it stands as a reminder of industrial excess and environmental negligence. This abandoned city, now a ghost town, proves the dangers of unchecked industrial activities and the threat it can pose to surrounding communities.

Picher was a goldmine for valuable resources

Picher’s inception dates back to late 1913 when rich deposits of lead and zinc ore were discovered. Named after O. S. Picher, owner of the Picher Lead Company, the town quickly grew and was incorporated in 1918. By 1920, it boasted a population of nearly 10,000 residents, bustling with activity and promise.

The deposits caused a population boom

The town’s rapid growth was fueled by the mining industry. Workers flocked to Picher from far and wide, drawn by the promise of employment and prosperity. The town’s infrastructure ultimately expanded to accommodate this influx, with schools, businesses, and homes sprouting up rapidly.

There was lots of money to be made

Picher was part of the Tri-State Lead and Zinc District, a region made up of parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. This district was renowned for its rich deposits and became the most productive mining field in the area. The city had approximately 14,000 mine shafts operating, and from 1917 to 1947, Picher’s mines produced over $20 billion worth of ore.

Picher’s impact during the World Wars

The town played a crucial role during World Wars I and II, supplying more than half of the lead and zinc used in the war effort. The mining boom brought prosperity but also sowed the seeds of the town’s eventual downfall. The byproducts of mining, particularly the massive piles of chat—waste rejected in the lead-zinc milling operations—would later become a source of severe health and environmental issues.

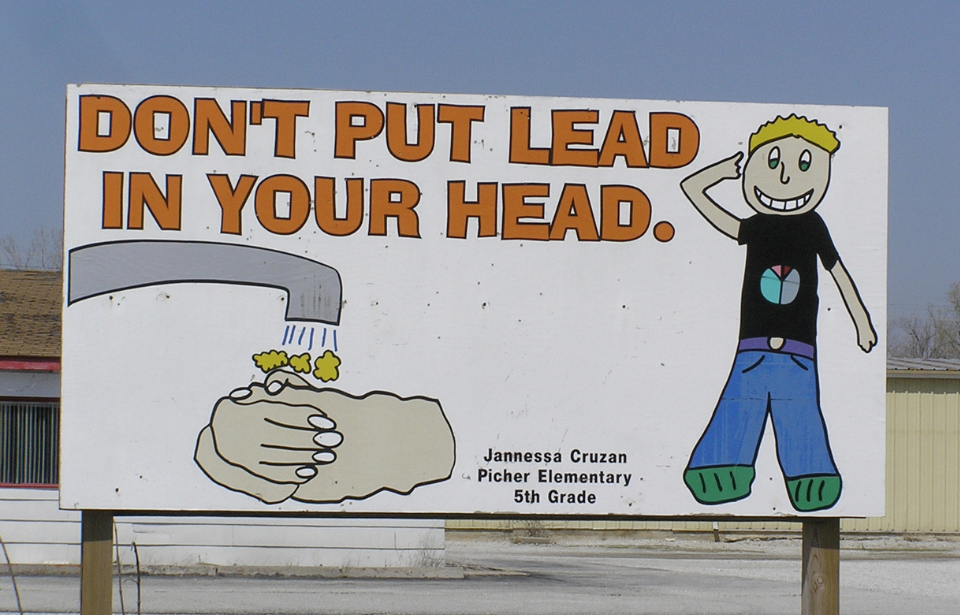

Toxic exposure led to serious health issues

The residents of Picher, especially the children, unknowingly faced grave dangers due to the mining byproducts. Exposure to lead, a primary component of the ore, posed significant health risks. Children played on the chat piles, unaware of the toxic exposure that could lead to brain damage, developmental delays, and other severe health issues.

There were long-term consequences

While the mines were closed in 1967, the miners themselves were not spared. Many suffered from silicosis, tuberculosis, lung cancer, and liver failure due to prolonged exposure to toxic substances. The health crisis in Picher was a silent but deadly consequence of the town’s mining legacy.

The Tar Creek Superfund Site

In 1979, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) designated the area as part of the Tar Creek Superfund Site. This designation came after water from the abandoned mines began seeping into Tar Creek, contaminating the groundwater and soil. The acidic water killed much of the downstream plant and animal life, raising alarms about the long-term environmental impact.

It was a huge environmental cleanup problem

Efforts to clean up the site were extensive but ultimately insufficient. Millions of dollars were spent funding remediation projects, but the scale of contamination was too vast. It has ultimately been considered a massive environmental disaster brought upon by unchecked mining operations.

A mandatory evacuation funded by a federal buyout

By 2006, a federal study revealed that 159 homes, businesses, and public buildings in Picher were at risk of collapsing due to significant undermining. This alarming discovery prompted U.S. Senator Jim Inhofe to call for a federal buyout for residents willing to relocate. Over the next two years, more than 200 families accepted the buyout and left Picher. This marked the beginning of the end for Picher.

The 2008 tornado

In 2008, an EF-4 tornado struck Picher, leveling the southern half of the town. The tornado left six people dead and many more injured, speeding up the evacuation that was already underway. The natural disaster left the town in ruins and discouraged any thoughts of resettlement. It kind of served as the final blow for Picher, effectively transforming it into a ghost town. Any remaining residents found it nearly impossible to rebuild their lives after all the destruction.

The final abandonment of Picher

By 2009, the federal buyout process was complete, and Picher ceased all municipal operations. However, a few residents chose to stay, clinging to whatever was left of their former community. In 2010, the U.S. Census recorded 20 residents within the former town’s boundaries. One of the last holdouts was Gary Linderman, who continued to operate his Ole’ Miners Pharmacy until his death in 2015. Following his death, there was no one left in the town.

More from us: Records of Survivors of Pompeii Found

What’s left of Picher has been left to decay over time, with its last-standing buildings serving as a reminder of the vibrant city it once was.