It seems like there is no person alive on the planet who would not be in awe of the grandeur of the Angkor Wat, the largest religious monument in the world, sitting at the heart of Cambodia. Angkor Wat is a vast temple complex, originally constructed as a Hindu worship site to the god Vishnu for the Khmer Empire.

Allegedly, Angkor Wat is the architectural manifestation of the sacred Mountain Meru in Hindu mythology, or what would be the equivalent to Mountain Olympus in Greek mythology. The temple complex gazes upon the West, which has created divided opinions among scholars concerning its symbolism.

In Hindu, the West designates the direction of death, which has led some to consider Angkor Wat’s first purpose as a tomb. At the end of the 12th century, the site had transformed into a Buddhist temple.

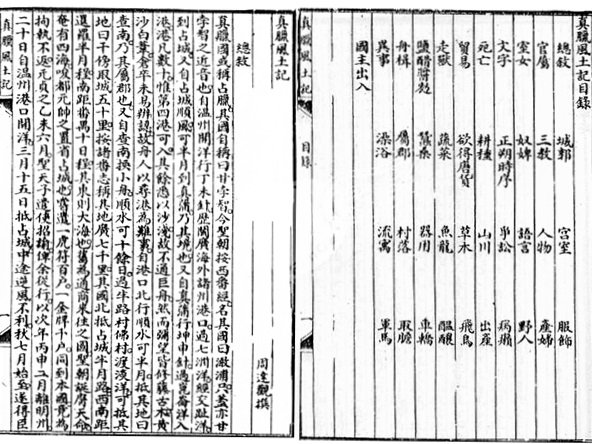

For centuries, travelers and explorers were captivated by the beauty of the Angkor Wat, and many reported on the mysterious site. One of the most interesting accounts comes from the Chinese traveler Zhou Daguan, who was sent as a diplomat under the Emperor Chengzong of Yuan of China. Zhou arrived at the temple complex in August 1296 and remained at the court of King Indravarman III until July 1297.

Zhou’s insights on the life and times of the early Angkor Wat are noted in The Customs of Cambodia, a book written during his diplomatic visit. He writes about the fascinating customs, religious practices and the role of women and slaves in this society. According to some of the unusual tales he also reported, it was believed by some that the temple was constructed in a single night by a divine architect.

Zhou would write of the Royal Palace: “Official buildings and homes of the aristocracy, including the Royal Palace, face the east. The Royal Palace stands north of the Golden Tower and the Bridge of Gold: it is one and a half mile in circumference. The titles of the main dwelling are of lead. Other dwellings are covered with yellow-coloured pottery tiles. Carved or painted Buddhas decorate all the immense columns and lintels. The roofs are impressive too. Open corridors and long colonnades, arranged in harmonious patterns, stretch away on all sides.”

He also depicts the royal procession of Indravarman III, descendant of the Angkor Wat creator, “When the King goes out, troops are at the head of [his] escort; then come flags, banners, and music. Palace women, numbering from three to five hundred, wearing flowered cloth, with flowers in their hair, hold candles in their hands, and form a troupe. Even in broad daylight, the candles are lighted.”

The Chinese diplomat further describes how the king and the women of Angkor looked. Only the ruler was able to be dressed in clothes that had an all-over floral design. The king also wore about three pounds of pearls around his neck, and gold bracelets and rings set with cat’s eyes at his wrists, ankles, and fingers. At public appearances, he would always hold a sword made of gold.

Zhou continues on the processions, “Ministers and princes are mounted on elephants, and in front of them one can see, from afar, their innumerable red umbrellas. After them, come the wives and concubines of the King, in palanquins, carriages, on horseback, and on elephants. They have more than a hundred parasols, flecked with gold. Behind them comes the sovereign, standing on an elephant, holding his sacred sword in his hand. The elephant’s tusks are encased in gold.”

Last but not least, according to the diplomat, the trading tasks with foreigners at Angkor Wat were performed by women. Zhou would additionally note that women aged very quickly. His remarks on the reasons were “because they marry and give birth when too young. When they are twenty or thirty years old, they look like Chinese women who are forty or fifty.”

Zhou’s depictions are considered accurate, although scholars haved identified inaccuracies. For instance, he describes the Hindu religious devotees in Chinese terms, as Confucians or Daoists, which would be wrong. Also, the measurements he provided about the length of the temples and their distance in the complex are not accurate either. However, the accounts can help us vividly recreate in our minds what life at the Angkor Wat was like at the end of the 13th century.

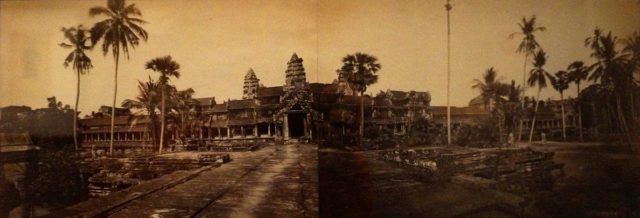

When the first Westerners arrived at the site, they were astonished at the sight of it. A Portuguese monk, António da Madalena, deemed among the first to arrive at Angkor Wat in 1586, would say that the place “is of such extraordinary construction that it is not possible to describe it with a pen, particularly since it is like no other building in the world. It has towers and decoration and all the refinements which the human genius can conceive of.”

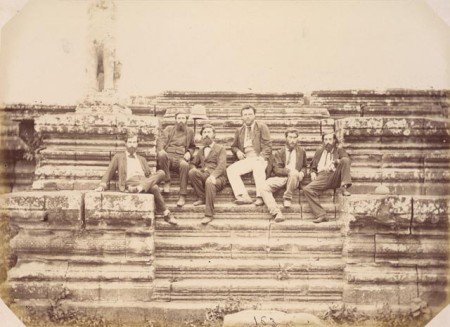

However, Angkor Wat would become more familiar in the West during the mid 19th century when the site was visited by the French naturalist and explorer Henri Mouhot. In his travel notes, he would glorify the complex by writing: “One of these temples—a rival to that of Solomon, and erected by some ancient Michelangelo—might take an honorable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome, and presents a sad contrast to the state of barbarism in which the nation is now plunged.”

In between the visits of the Portuguese monk and the French naturalist, life at Angkor Wat had notably diminished. Reportedly, by the 17th century, the complex was not completely abandoned but still functioned as a Buddhist temple. Fourteen inscriptions dated from that period and discovered in the nearby area, affirm that it was Japanese Buddhist pilgrims who had established small settlements along the local Khmers.

In those days, Angkor Wat was in fact mistaken by the Japanese to be a famed Jetavana garden situated in India; a place where the Buddha had given the majority of his teachings.

It was a challenge for researchers to piece together the history of the monumental site accurately. Eventually, they did so through clearing and restoration work on the whole complex. It was unusual that there was an absence of ordinary dwellings or signs of other settlements. There were no tools for cooking, weapons, or clothes whatsoever, typically found at other ancient sites. It was only the monuments. The restorations took place during the 20th century and focused mostly on the removal of concentrated earth and vegetation.

Some serious casualties at Angkor Wat followed in the late 1980s and early 1990s when art thieves, mostly operating out of Thailand, claimed almost every head that could be chopped off the structures, including reconstructions.

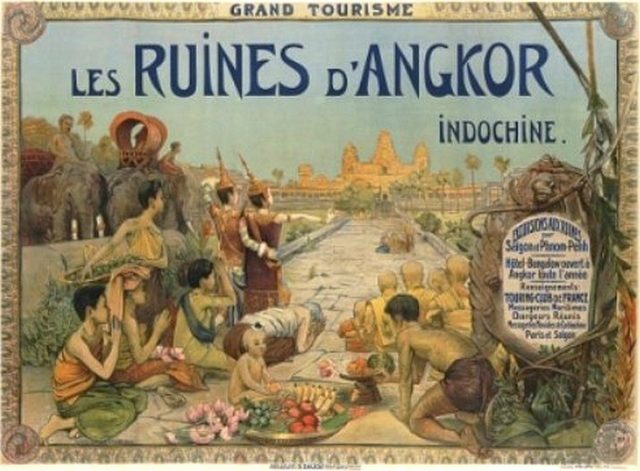

To date, the complex remains a powerful symbol of Cambodia and a reason for great national pride, which also determined the country’s diplomatic moves towards other countries such as France or Thailand in the past. The imposing legacy of Angkor Wat and other sites of the Khmer empire in the region had been the reason for France to adopt Cambodia under a protectorate in 1863, thus trespassing territories controlled by the Siamese (Thai), and taking charge of the ruins. The events then led Cambodia to quickly reclaim the lands in the northwest of the country which had been under the Siamese for several centuries.

In December 2015, researchers on behalf the University of Sydney announced new findings at Angkor Wat which concerned previously unseen groups of buried towers, probably built and demolished during the construction of Angkor. The findings could also offer answers to questions which have puzzled researchers for decades.