The town of Lonaconing in Maryland was perfect: it had coal reserves and was located along two railways that ran through the town – the Cumberland and Pennsylvania railways.

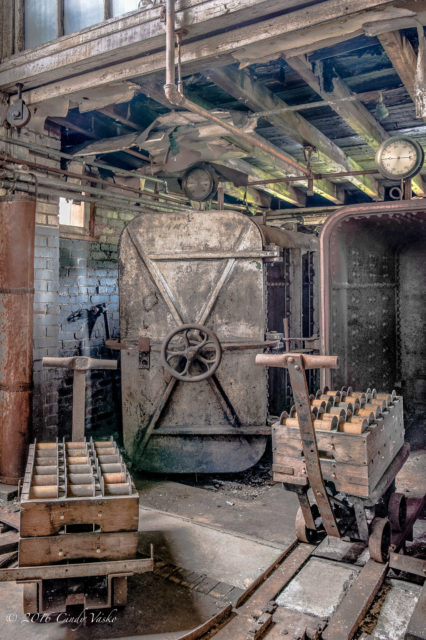

In the early 1900s, Klotz Throwing Company, led by George Klotz, was looking for a place to build a silk thread factory in coal mining areas served by railways. The reason coal mining areas were top of Klotz’s list was because that coal could feed the steam technology at the mill, and there was also lots of cheap labor around.

Klotz Throwing, which was based in New York at the time, acquired land in Lonaconing. In August 1905, the construction of a silk throwing factory began. At that time, it was the third silk mill in the state, and the finished factory had an area of 48,000 square feet.

At the factory, raw silk would be wound into a thread, which would then be sent on to be used in the production of silk fabrics and clothes. The raw silk was purchased from other countries then went through the process of being washed, dyed, and dried at the factory. After that, it was wound up in skeins of thread.

The official opening of the Lonaconing factory took place in April 1907. About 80 percent of the employees were women, although the company also used to hire children.

In 1916, the mill was expanded and slightly transformed, and once again two years later. In the spring of 1918, the demand for silk increased, and the factory had to be expanded yet again. Business was booming.

In 1920, the factory was noted as having 359 employees, the highest in its history. The income and trading that Klotz’s mill provided enabled the surrounding area to develop. It is reported that his business brought about $100,000 to the Lonaconing economy annually since the beginning of 1922.

In October 1929, the world economic crisis known as the Great Depression began. At this time, demand for silk fell sharply as it was considered a luxury. In addition, coal mines began to close.

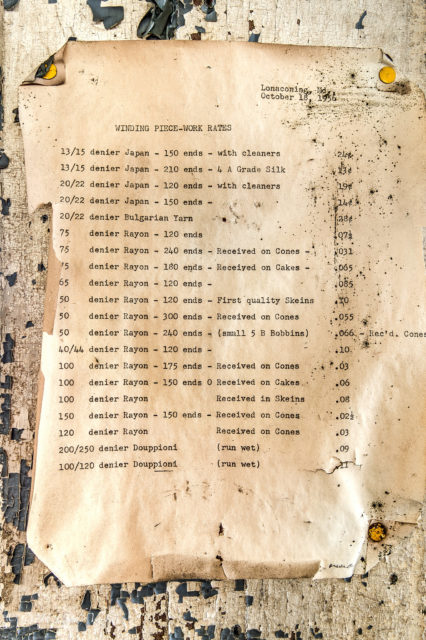

Klotz filed for bankruptcy, but in 1932 he was able to reopen the plant. The name of the mill was changed to General Textile Mills. However, the number of workers it employed had decreased, as had the wages of those who worked there.

During World War II, supplies of raw materials for silk production from Japan were suspended. Business had been difficult before that since orders for silk were small or completely absent after the end of the Great Depression. But this new hindrance to trade forced the plant to close from January to October 1945.

After it reopened, about 200 people worked at the plant but on a reduced salary. After the war, viscose and other synthetic fabrics began to be used for clothes production as they were much cheaper than silk.

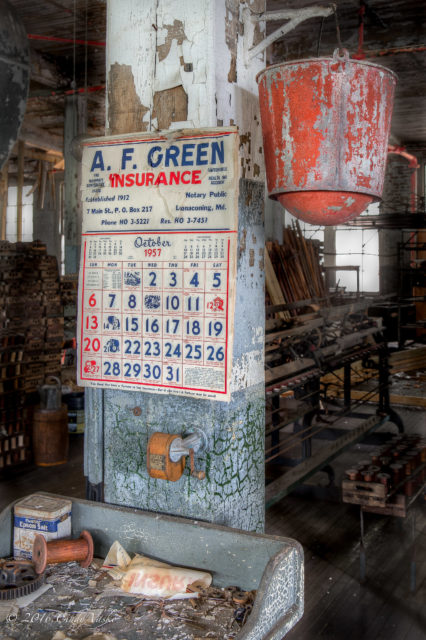

In the summer of 1957, the mill workers went on strike, demanding higher wages. However, the company was not able to raise salaries, and it had to cease operations immediately.

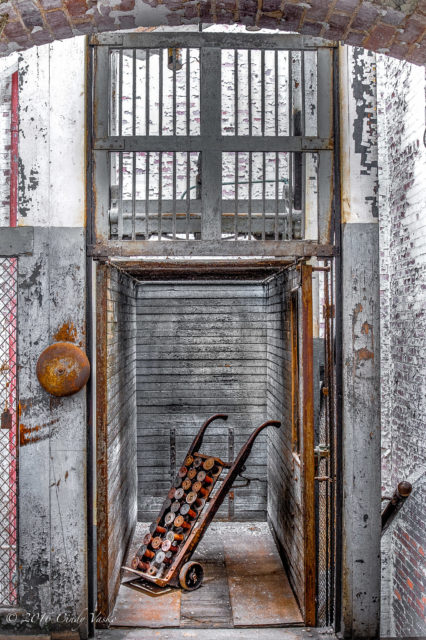

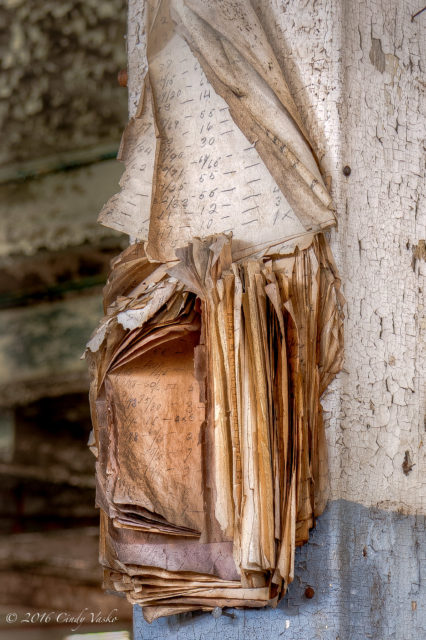

The official closing date of the mill was July 7, 1957. Because this decision to close was executed so quickly, many personal and work items were left in the building, and workers were forbidden to enter and remove them. Visitors today describe it as “a time capsule.”

Over the course of several years, only a few people entered the factory, and their role was to perform basic equipment maintenance.

Lonaconing Silk Mill is considered one of the last pristine silk factories in the United States, which is a very rare thing to be.

In 1978, the abandoned factory caught the eye of Herbert Crawford. He’d been convinced that various businesses were interested in operating from the mill again. However, there were no such businesses, and the seller later went to jail on swindling charges.

But Crawford takes his ownership seriously. He is always trying to obtain financing in order to carry out roof repairs and various maintenance.

About ten years ago, he opened the mill to tourists and photographers who could access the building in return for a donation. Crawford has made about $18,000 this way, but this is still a far cry from the amount he’d need to carry out the necessary maintenance, which could be in the area of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In 2007, the George’s Creek Watershed Association nominated the Lonaconing Mill to be included on a list of most endangered historic sites, a list run by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Crawford has received various offers to buy the equipment or materials from the building. However, he has turned down such offers and still hopes to make it into a museum.

But as time passes, the building becomes more and more derelict without the means to repair it. Large holes can be observed in the roof, most of the windows are broken, and the water that penetrates inside has encouraged the floors to rot.

Thank you, Cindy Vasko, for giving us permission to share your images with our readers. Go check her Flickr account and enjoy more amazing photographs.

Another Article From Us: The Selma Mansion That Has Been Lifted From the Pages of a Horror Novel