The Palace of Knossos is the largest and most impressive remnant of the Minoan civilization. This ancient civilization thrived on Crete 2000 years B.C. and planted the seeds for the later classical culture in Greece and throughout the Mediterranean.

The roots of the Western culture lie here. The remains of the colossal building are crucial to our understanding of the Minoans’ history, art, and architecture. Despite the questionable restoration work by archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, the palace still manages to convey to visitors a sense of its former glory.

“They fashioned a tomb for you, holy and high one,

Cretans, always liars, evil beasts, idle bellies.

But you are not dead: you live and abide forever,

For in you we live and move and have our being.”

(Epimenides of Knossos)

The history of the palace

The palace of Knossos was erected on the ruins of an older building constructed around 2000 BC and likely destroyed by the earthquake caused by the gigantic (ca. 1628) eruption of the volcano on Thera (the present-day island of Santorini).

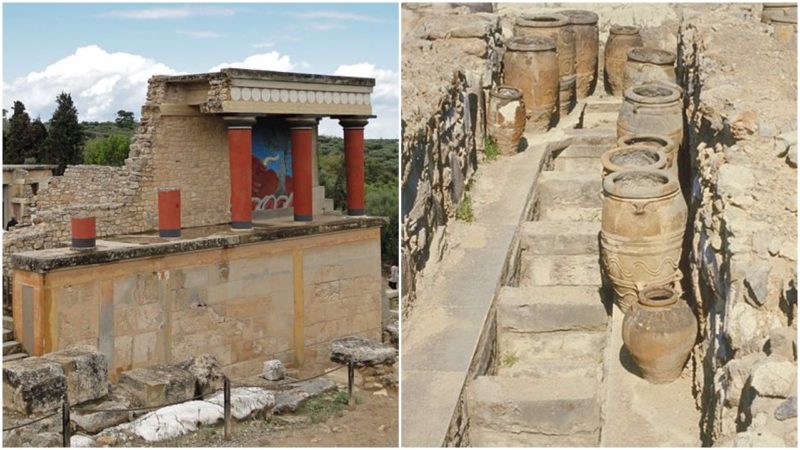

Arthur Evans was the archaeologist who, in 1900, began to excavate Knossos. He was also in charge of restoring the ruins of the palace.

He tried to recreate the original appearance of the building by rebuilding the missing parts with modern materials like reinforced concrete. For this reason, he was later much criticized. But he was certainly not the only archaeologist to work this way during his era.

However, the added materials are not easily recognizable. The columns, for example, were originally made of wood and did not survive into the modern age.

The existing concrete columns are painted red and black with the same colors typically used by the Minoans and give a general idea of the palace’s original appearance.

The palace is enormous and grew over years of use to occupy about 20,000 square meters. Walking through its complex multi-story buildings, one can understand why the Palace of Knossos has been associated with the mythological labyrinth of the Minotaur.

The legend

According to Greek mythology, the building was designed by the architect Daedalus. King Minos, who commissioned the palace, kept him prisoner to make sure he would not reveal the secrets of the project. Daedalus, who was a great inventor, built two pairs of wings to fly away and escape from the island with his son Icarus.

The father warned his son not to fly too close to the sun because the wax that held the wings together would melt. But, in a tragic turn of events during the escape, young and impulsive Icarus flew higher and higher until the sun melted the wings and the young man died falling into the waters of the Aegean Sea.

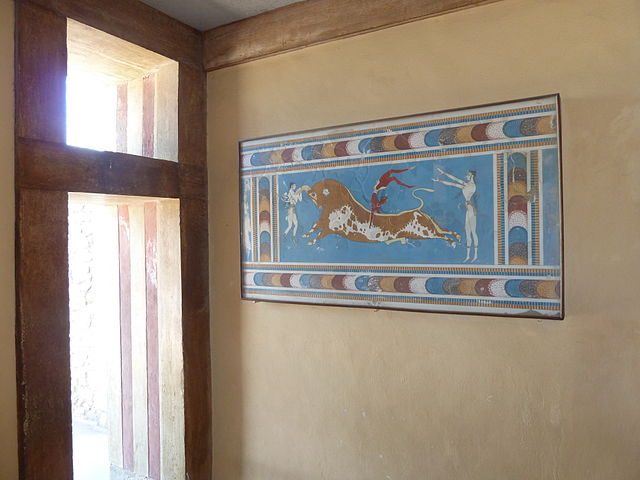

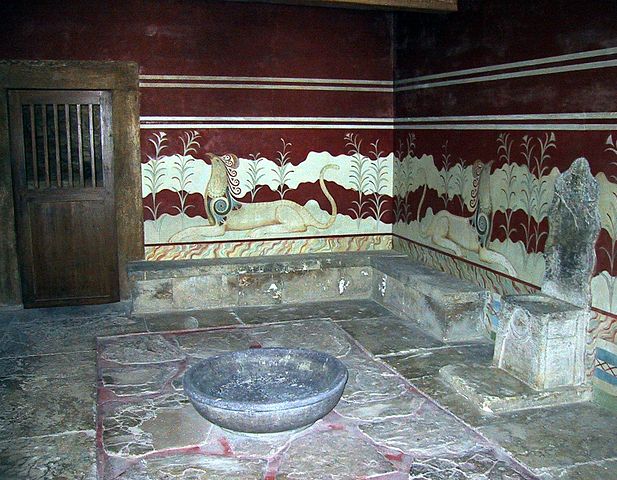

Greek myths also tell that the labyrinth at Knossos was home to the monstrous Minotaur, later slain by Theseus. Though the legend is enduring, walking through the ruins of Knossos, it’s hard to imagine that it was a place of torment and death. The frescoes that decorated the elegant walls speak of a people with a rich and joyous approach to life.

The palace

The living space of the complex included the accommodation of the king, queen, and administrative officials, as well as halls for worship and receptions. The central area was a courtyard where performances of bull-leaping by gymnasts were carried out. Bulls were sacred animals to the Cretans, as evidenced by the numerous frescoes found in the building. The dangerous bull-leaping ceremonies are thought to be a historical basis for the Minotaur myth.

The bathrooms of the Queen’s apartments, with underground pipes, sewers, and drains; Minoan technology was even able to provide running hot water.

Many of these buildings were destroyed and abandoned in the early part of the 15th century BC, although Knossos is thought to have remained in use until it was destroyed by fire about one hundred years later. Knossos showed no signs of ever being a military site. It had neither fortifications nor stores of weapons, so the reasons for its abandonment remain a mystery.