Just outside of Cardross, hidden away in the woods, lie the remains of St. Peter’s Seminary. Built in the 1960s by the Gillespie, Kidd, and Coia architectural firm as a college for priests, it has been closed and abandoned since the 1980s.

Many consider the building to be an important modernist masterpiece and Scotland’s most important architectural achievement.

Nevertheless, even being listed in Category A, the highest level of preservation for a building of special historic interest, it’s a shame that it’s still in a desolate, derelict state. The World Monument Fund included it in their 100 Most Endangered Sites list for 2008.

Recently, plans have been made to restore and protect this significant, unique construction. The Heritage Lottery Fund gave £3,806,000 to Glasgow-based arts organization NVA, lead by artist Angus Farquhar, to transform the site into an arts venue. Also, Creative Scotland contributed £400,000 to the project

The origins of St. Peter’s Seminary began in 1946 after a devastating fire destroyed the original seminary in the Glasgow suburb of Bearsden.

Discussions about a new theology school started in 1953, and the plans were finalized in 1961 when building commenced. Isi Metzstein and Andy MacMillan, employees of the Gillespie, Kidd, and Coia firm were the two masterminds behind the designs.

Using an old Victorian mansion at the center of the Kilmahew estate as a template, they created something very radical. Their incredible, audacious effort of juxtaposing the old house with new buildings around it is still considered a work of art and one of the most important architectural creations of the mid 20th century, not just in Scotland, but in the world.

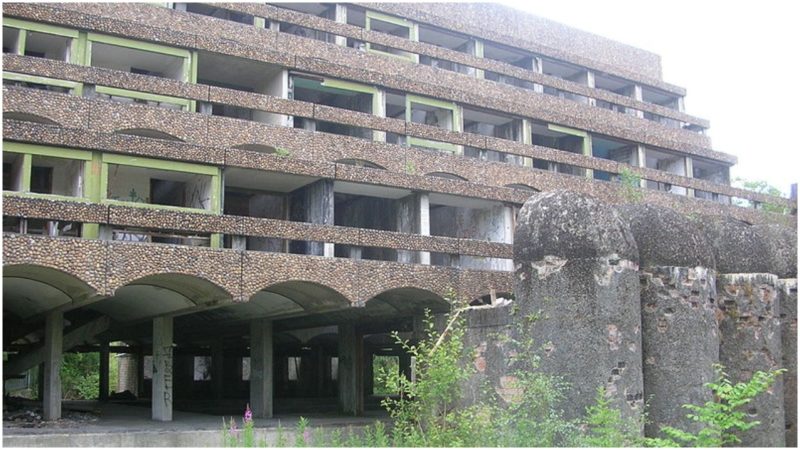

An entire new main block was built, with a convent block, a sanctuary block, and a classroom block also added, and the old house was the place where the students would have been settled. This distinctly modernist and brutalist construction was very much influenced by the work of Le Corbusier.

However, by the time the seminary was completed in 1966, it was already in trouble. The Roman Catholic church had decided that priests should train in communities rather than isolated seminaries. On top of that, the number of candidates entering the priesthood was declining, as well as church attendance.

As a result, the school, which was designed to house and train 100 would-be priests, never reached its full capacity and was counting only 20 students by the late 1970s. Finally, other problems like significant water entry in the building and maintenance difficulties were enough for the owners to decide to bury the hatchet. In less than 20 years, St. Peter’s became obsolete and in February 1980 it closed its doors permanently.

Since then, the building was left to rot, totally neglected and open to the elements. Everyday vandalism and a large fire left the building in permanent decay and ruin. Now, most of the woodwork and glass are gone, with only key aspects of the original design still visible. In October 2005, it was named Scotland’s greatest post-World War II building by the architecture magazine Prospect.

But despite being abandoned and out of use for over 30 years, it continued to attract many visitors, urban explorers, and photographers.

Now, we can all hope that the latest plans for preserving what is left of the building and turning it into an arts venue will soon succeed.