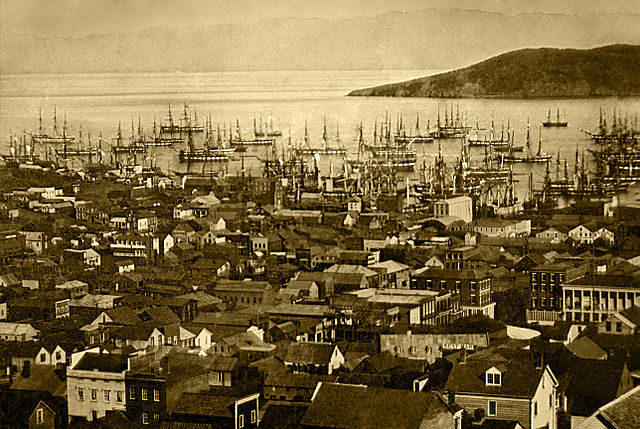

“Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!” Echoing through the streets of San Francisco in 1849, these were the words of Samuel Brannan, one of America’s first gold prospectors, distinguished businessmen, and prominent journalists.

Screaming, yelling and waving a bottle of gold dust like a mad man, Samuel, the founder of California Star, is considered the first man to publicize California’s Gold Rush.

His many articles about the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in the western Sierra foothills that same year dragged men and women in abundance to California.

Prospectors from across the States and all over the world rushed with their picks, shovels, and gold pans to some of the most remote corners of the state. Searching for deposits, loose flakes, and gold nuggets, hoping to be the first to put their hands on the gold that was now free for the taking.

What is now referred to as “the Land of the Free and Home of the Brave” was then the Land of Gold. Migration was set in motion as never before. There was a gold rush going on, and it seemed like everyone wanted to be a part of it.

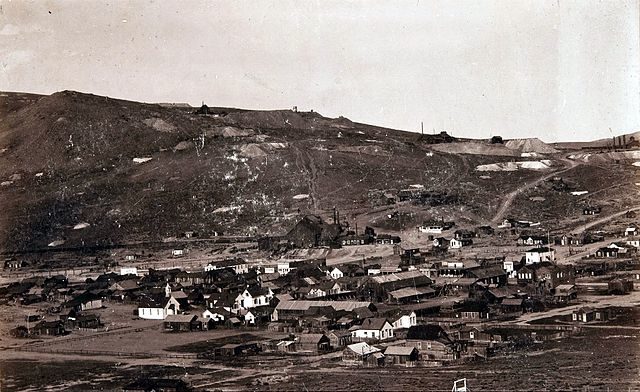

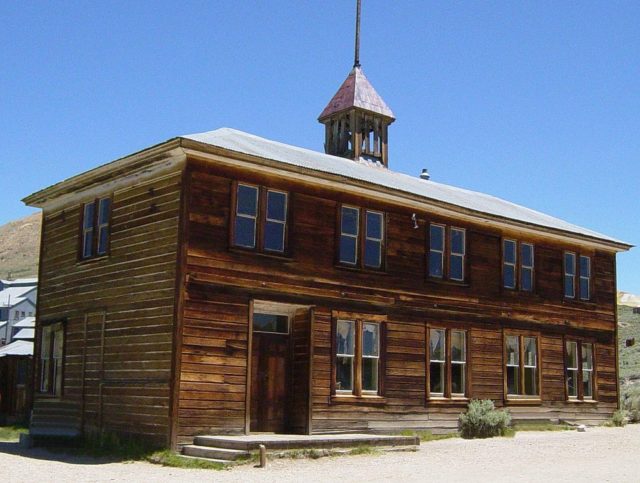

Bustling gold mining centers popped up virtually out of nowhere, one of them being Bodie, a Wild West-style town buried deep in the Bodie Hills, east of the Siera Nevada mountain range.

Named after the ambitious prospector W. S. Bodey, who in 1859 accidentally discovered gold in the vicinity, the town first started as a small mining camp. Soon after, many people arrived after Standard Company discovered a profitable deposit of gold-bearing ore.

The camp quickly transformed into a flourishing, yet wrongly named city. Allegedly, Camp Bodey became the City of Bodie after the town’s painter misspelled the sign. However, the settlers preferred this “new” version, so the name stuck. Too bad Bodey perished in a blizzard that same year and had no say in this.

The city became an actual city in the late 1870s when flocks of hopeful people came to this now bustling gold-digging destination. At its peak, some time between 1879 and 1882, Bodie counted as much as 5,000 to 7,000 people and 2,000 structures, including the Miners Union Hall, Wells Fargo Bank.

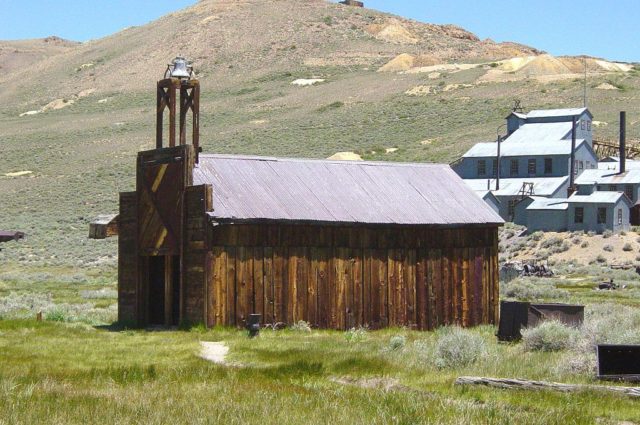

Along with schools, liquor stores, a stable house, a fire house, countless private homes and hotels, its own Chinatown, a Methodist church, and of course a nearby morgue and cemetery on the outskirts of the city.

Along with the many businessmen, mine operators, and miners that arrived, Bodie attracted hundreds of saloon-keepers, gamblers, prostitutes, travelers, and an unprecedented number of so-called “Bad men”. Desperate, violent mercenaries and gunslingers also in search of gold overflowed the red light district and its 65 saloons.

As a general rule, a bustling economy always induces high crime rates as well, so gambling, gun-fighting, stage robbing, murders, shootouts, barroom brawls, and stagecoach holdups were so regular that Bodie became an infamous location widely known by its lawlessness instead of its riches.

Given its reputation, it is no surprise that when people were moving to the city, they reportedly prayed “Goodbye God! We are going to Bodie”.

The decline

Besides the lawlessness and the omnipresent violence, Bodie was faced with additional perils and hardships as well. Known to have a dry-summer subarctic climate, with scorching summers but long, frosty winters and deadly winds sweeping across the valley at close to 100 miles per hour.

The city was put to the test at the end of 1878 when it was hit by a savage winter in which hundreds died. This was on top of the numerous mining accidents and explosions of powder magazines that used to fill the morgue on a daily basis. But the city and its people endured, at least for a while.

In 1892, a disastrous fire struck the city and forever closed the two major mines that were still operating successfully. The mine closings and the abandonment of the Bodie Railway in 1917 confirmed what was feared – that the city was dying, and slowly but surely starting to look like a ghost town.

From a peak of 10,000 inhabitants in the 1880s, the population of Bodie rapidly declined, and at the start of the 20th century, only 120 people still lived in the city.

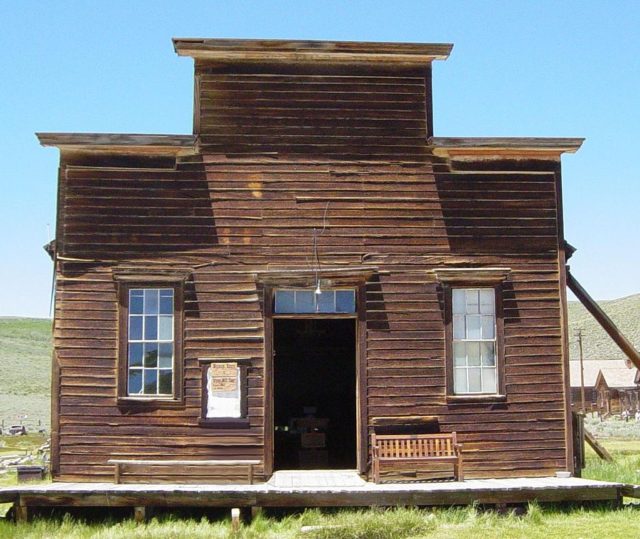

When people were fleeing the city, they simply packed what they could on one wagon or truck and left everything else behind. Now, most of what was left due to haste still lies untouched and perfectly preserved.

In 1932, another devastating fire destroyed much of the town and by the 1950s, Bodie officially became a ghost town. Now, after so many years, the city is kept in a state of arrested decay where the buildings are protected but not restored. This really gives a creepy image to the town, as if it is frozen in time; a town where ghosts live when no one is watching.

It is no surprise that Bodie, old and deserted as it stands nowadays, inspired many romantic and superstitious visitors to claim that this ghost town was really a “ghost town”. And can you blame them? With 168 remaining structures intact it represents an entire townful of potentially haunted houses. As you are walking down this frozen eerie scenery, the morgue and the cemetery added, your imagination surely can run wild.

Hardships and violence aside, Bodie was a thriving, functioning community, but unfortunately, as the gold rush ended, so did the city. With brief days of glory and long decades of decline, this city is now the best representative the fast-paced gold rush era of the 19th century. Today, it is a real gem, preserved as it was standing in its times of grandeur.

The town was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1961 and in 1962 it became the Bodie State Historic Park. It is now recognized as the official gold rush ghost town in California.