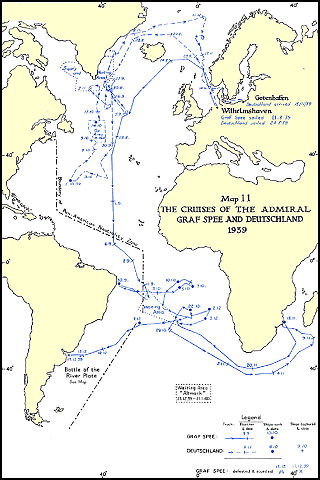

On August 21, 1939, four months before Germany’s invasion of Poland, the German naval ship Admiral Graf Spee departed from Wilhelmshaven Port in Lower Saxony under the command of Captain Hans Langsdorff. Circumnavigating the British Isles at a cautious distance, she cruised through the Atlantic towards the coast of South America, where she was destined to enter the first significant naval battle of World War II.

Langsdorff’s initial orders were to remain at sea and undetected. Once the war had officially begun, he received the command to attack only British merchant ships in the South Atlantic but to avoid risking any engagement with enemy ships. Admiral Graf Spee was supported by the tanker Altmark for fuel and provisions.

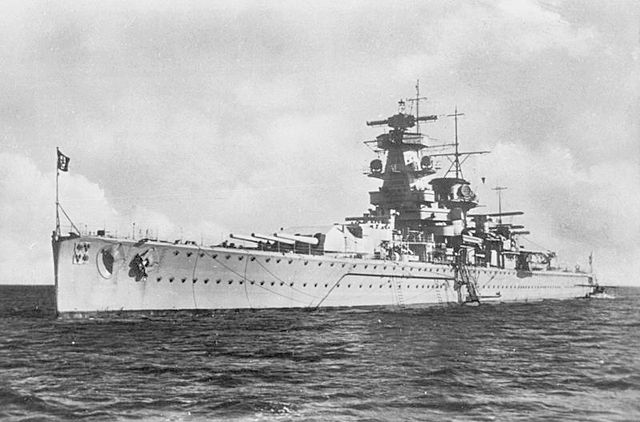

Admiral Graf Spee and her two sister ships, Deutschland and Admiral Scheer, had been built during the interwar period. In order to keep within the limitations of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles (which formalized the punishments that were to be imposed upon the German Empire at the end of WWI), Germany could not build ships that had a displacement of more than 10,000 tons.

While this hampered their ability to match the biggest British and American battleships, fitting out these three armored cruisers with diesel engines rather than relying on steam power meant they could not only save weight but also accelerate faster and run for longer. The downside? The diesel engines were far less reliable.

Officially known as Panzerschiffe (armored ships), they became known by the Allies as “pocket battleships” because of their size and impressive array of heavy guns.

On September 30th, off the coast of Brazil, Admiral Graf Spee came upon her first victim: the British steamboat Clement. Langsdorff allowed the crew to scramble into their lifeboats before a volley from Graf Spee sank the merchant ship. Even though Clement’s captain disobeyed his order not to send a distress signal, Langsdorff treated him well. The captain, chief engineer, and another man were taken as prisoners for questioning but later handed over to a (neutral) Greek steamer.

For his mercy, Langsdorff was dubbed “head-to-toe a gentleman” by the British, who admired his honesty and uprightness. His raids resulted in no casualties, but every chance he gave his victims to radio through a distress message was a step closer to the demise of Graf Spee.

October saw Graf Spee capture and sink a further four British merchant ships before heading into the Indian Ocean to both evade the closing net of Allied warships and to hunt the lucrative wool shipments that would be taking the trade route from Australia to Cape of Good Hope. Having found no prey apart from a small British tanker, which was caught by surprise and scuttled, she returned to the Atlantic after being sighted by the Dutch SS Mapia.

After regrouping with the Altmark in late November, four days were spent making repairs to the engines. Patched up as well as could be done at sea, Langsdorff decided his ship was sound enough to make one final sweep along the coast of South America before returning home for a full overhaul.

A further three prizes were captured, looted, and sunk. From the third of these, the freighter SS Streonhalh, a German seaman was able to retrieve secret documents that the captain had thrown overboard in a weighted bag. The documents revealed that four unescorted British merchant ships were due to leave Montevideo on December 10th.

On the morning of December 13, 1939, the Admiral Graf Spee was laying in wait for them to appear on the horizon, 300 miles from the port.

By now Graf Spee’s reconnaissance plane was disabled and there were no spares left to repair it. Langsdorff pressed on, regardless of reports that several British and French warships were scouring the area to intercept them near the estuary of the River Plate.

At the time, the British admiral Henry Harwood had only the cruiser HMS Exeter, which was equipped with 7.8-inch guns; and the two lighter naval ships Ajax and Achilles, each having eight 5.9-inch guns. The German naval ship was equipped with six 8.5-inch guns as well as eight 5.9-inch guns. Reportedly, it was estimated that there were almost no chances of the British facing a direct naval attack.

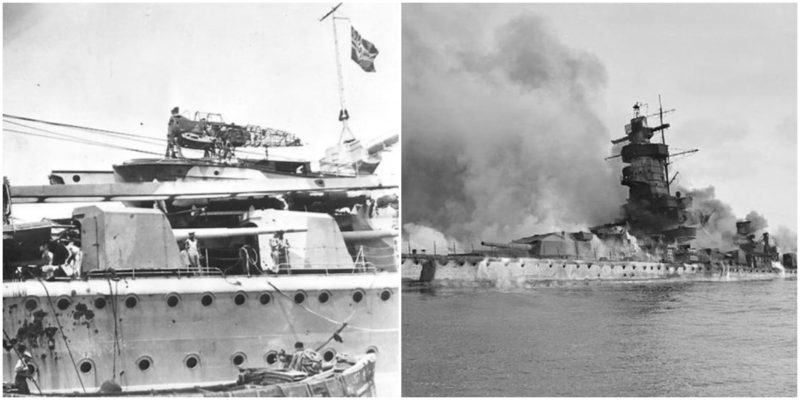

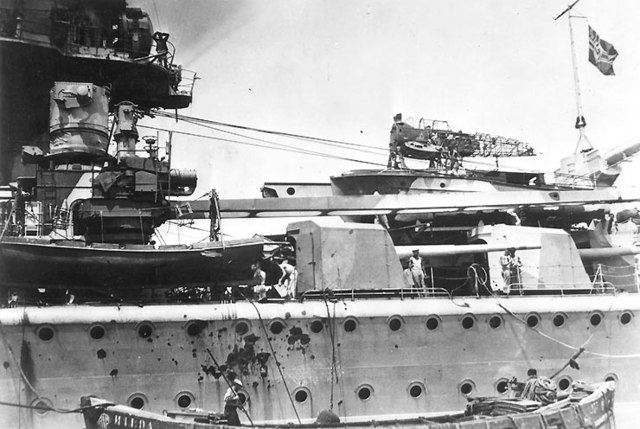

During one of its circulations, the Ajax spotted the Admiral Graf Spee and signalized its position. The British squadron divided itself into two units and attacked the German naval ship. The Germans were first to open fire and caused serious damages to the Exeter. However, one of its grenades hit the commanders’ tower of the German naval ship. Despite the grave havoc that Ajax and Achilles faced, they sustained fire ceaselessly.

The Admiral Graf Spee tried, by using a smoke-screen, to retreat from the battle. After the successful outcome of this operation, she headed to Montevideo, the capital of neutral Uruguay. The Germans pleaded for two weeks of accommodation at the port to make repairs. Nevertheless, the British succeeded in persuading the Uruguay government to limit the accommodation to no more than 72 hours. Actually, the international convention allowed only 72 hours of anchoring in a neutral harbor.

At the same time, the newspapers spread false information that a large British fleet was patrolling the port. But in reality, the British had only a single fully-equipped ship near them at that moment. After an intensive telegram exchange, Berlin decided that Admiral Graf Spee, primarily its important equipment, must not be captured by the Allies. Langsdorff received an order to destroy his own ship.

On December 17th, at sunset near the Port of Montevideo, an extreme explosion broke out. The heavy naval ship Admiral Graf Spee began to sink slowly in front of numerous eye-witnesses. At that very moment, all the Germans performed the Nazi salute on the shore, except for Captain Langsdorff who saluted in the traditional military way.

This act signified the end of Admiral Graf Spee, a ship that had destroyed a great number of British merchant ships. The German equipage was interned in Buenos Aires. Three days later, Langsdorff committed suicide, suggesting that he saw the sinking of his naval ship as his own sinking as well.

He was found in his own room, lying dead on the German Imperial flag instead of the Nazi flag. The British preserved the memory of him as a courageous soldier, earnest and moral, just as a perfect gentleman should be. In 1956, a British war movie entitled The Battle of the River Plate was filmed about the events of this famous World War II battle.

The ship sank in shallow water just off the breakwater of the harbor entrance at a depth of approximately 36 feet, and its radar antenna was still visible. In 1942/1943 the British used an Uruguayan company as a front and bought the salvage rights from the German Government. They hoped that they would find some secret technology, and indeed they had success. The radar rangefinder was located and examined. Later, they used the acquired knowledge to develop their own technology. During this operation, parts of the wreck were broken up on site.

However, great parts of the wreck still remained in the water until the beginning of the 21st century. It became a danger for navigation, and between 2004 and 2006 large sections of it, like the gunnery rangefinder and a bronze eagle weighing between 350 and 400 kg, were raised from the water. Today, very little remains.