A team of marine archeologists have documented an 18th-century slave shipwreck discovered off the coast of Mozambique. The vessel is suspected to be the French slave ship L’Aurore, and the wreck could be key in shaping our understanding of the living conditions aboard similar vessels. While over 1,000 ships from the transatlantic slave trade sank around the world, less than 12 have been located and documented, leaving much still unknown.

Discovering the wreck of L’Aurore

In 2015, the Slave Wrecks Project (SWP) coordinated the search for L’Aurore. The program, which involves several organizations, aims to “draw attention to the study of slave shipwrecks and strengthen skills and capacity for research in maritime archaeology.” To do this, the team searches for slave ships across the world and also trains Africans and people of African descent in underwater archaeology.

Notably, SWP began its search after archival researcher Richard Allen found a document in Mauritius that contained an account of the wreck by L’Aurore‘s captain. He brought his findings to SWP’s attention, which located the wreck believed to be slave ship in 2022.

While the discovery largely flew under the radar of the larger community of Mozambique, it’s an incredibly important discovery.

Story of L’Aurore

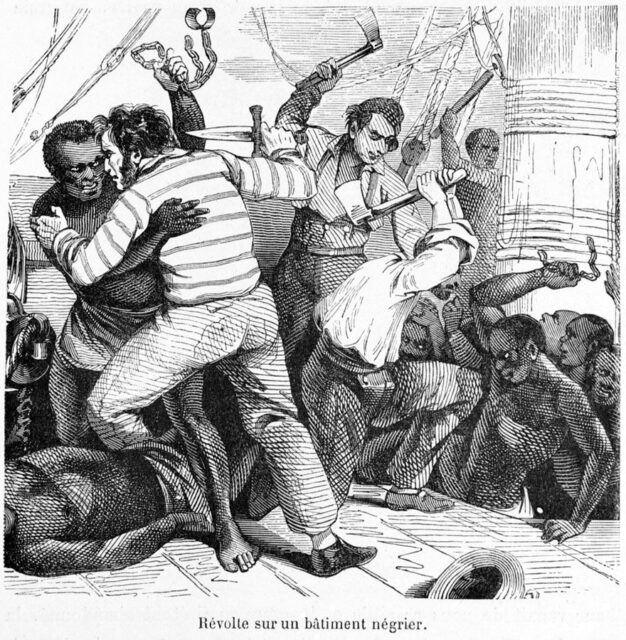

The captain’s account states L’Aurore left present-day Mauritius for Mozambique to pick up enslaved people in November 1789. The vessel’s final destination was the French Caribbean. In January of the next year, while they boarded, the 356 already aboard tried to stage a mutiny. Four drowned. To prevent another mutiny from occurring, the crew locked the men below deck.

A month later, a storm hit when L’Aurore was readying to depart, sinking the slave ship. The crew refused to let the enslaved men out until the vessel was already sinking, resulting in the deaths of 331 people.

Celso Simbine, one of the Mozambican maritime archeologists exploring the wreck explained that, today, “L’Aurore is a symbol of resistance and revolt of black people refusing to be taken out of their land.” Steve Lubkemann, an American maritime archaeologist and the co-founder of SWP, added that it’s a reminder that enslaved people didn’t “go quietly,” an oft-forgotten fact.

Much of what life was like aboard slave ships is still a mystery. So few wrecks connected to the transatlantic slave trade have been documented as archeological sites for one reason: money. The ships typically didn’t carry much gold, so people weren’t motivated to search for them. However, wrecks like that of L’Aurore are evidence of the crimes that were committed against enslaved people during the slave trade.

An important piece of history

Today, the location of what’s believed to be L’Aurore‘s wreck rests near Fort São Sebastião, a 16th century fort used in the Portuguese slave trade.

It should be noted that the wreck being studied hasn’t been officially identified as L’Aurore. However, there’s a lot of evidence to support it being the same vessel. The captain’s account describes the same area, French techniques were used to build the slave ship and the ballast comes from Mauritius, the last port of call before Mozambique.

Moreover, beyond being an important symbol of the resistance of African people, the wreck is archeologically important. It’s incredibly well-preserved and may be the best example of an 18th-century slave ship ever found. The research done will help archeologists understand the structure and living conditions aboard other similar vessels.

Slave Wrecks Project (SWP) won’t raise L’Aurore

The diving team in Mozambique was made up of young, Black maritime archeologists from Mozambique, Senegal and Brazil. They worked from Mozambique for two weeks, trying to understand the structure of L’Aurore.

Aboard the ship, the team discovered ceramics, a lead shot and a barrel top. Although they may remove some artifacts for study or display, there’s no plan for raising the entire vessel. Lubkemann explained, “You don’t need to raise the ship to tell the story. Even if the bodies are not there, it is a site of tragedy. And you treat it with respect.”

The team, including community stewards, dove in the morning to map, excavate and photograph the vessel. They took classes in the afternoon on project management, dive safety and the principles of artifact recovery.

Previous slave ship discoveries

Over 12 million Africans were enslaved during the transatlantic slave trade. Notably, as a former Portuguese colony, Mozambique was a huge part of the trade in the 18th and 19th centuries; Portugal was one of the earliest and largest participants, with slavers selling hundreds of thousands of Mozambican people.

The SWP works to provide local communities with the knowledge and resources to identify and preserve stories of wrecked slave ships in local waters. They hope this will help Africans tell their own histories, instead of having the history of the slave trade told from a European perspective.

More from us: Ostwall Fortifications: The World War II-Era Defensive Line That’s Become a Bat Reserve

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our Today In History newsletter!

SWP is researching other slave ships, as well. In 2015, the team identified the Portuguese slave ship São José, near the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. The ship sunk around 1798. It was the first recorded wreck discovered of a ship that sank in transit with enslaved humans.